On March 31, 1962, the day he turned 35, Cesar Chavez marked his birthday by quitting his job. This unusual (at the time many would have said called it foolish) choice of birthday observances changed the course not only of his own life, but also of the U.S. labor movement and the Catholic Church. Mr. Chavez quit in order to establish a labor union for migrant farmworkers.

He knew well the life of the campesino: backbreaking work under dangerous conditions for demeaning pay that did not begin to provide adequate food and shelter. Cesar Chavez spent his entire childhood and many of his young-adult years living in the miserable circumstances he intended to combat with a union. But it would be a mistake to see his occupational move as a desperate effort to improve his own difficult situation.

Since 1952, Mr. Chavez had managed to achieve what most farmworkers could only dream of: steady and meaningful employment in a comfortable environment with pay and benefits that reasonably supported his growing family. As an employee of the Community Service Organization, an early and important California Latino civil rights group, he conducted voter registration drives, protested police brutality and led evening citizenship classes at neighborhood schools. In 1962, he was C.S.O.’s general director and, by all accounts, a success at it. He had already spent 10 years out of the fields. He had even turned down a job offer from Sargent Shriver, head of the Peace Corps, to oversee the group’s operation in four Latin American countries.

So quitting his job was not a move of calculated self-interest. A bit reckless, the choice destroyed the security he had established for himself, his wife, Helen, and their young children. Mr. Chavez’s later achievement would have been impossible without the generous cooperation of his wife and children. For as he spent the next several months crisscrossing the San Joaquin Valley to talk with farmworkers in their shacks and garage apartments, Helen worked in the fields to support the family.

Structures of Sin

Cesar Chavez’s organizing efforts also placed him at serious personal risk. For the previous half century, California agribusiness had opposed, by means both legal and illegal, all attempts at labor organization. The Associated Farmers had coordinated a notoriously harsh campaign against early unionization attempts by field workers; it included widespread violence and mass arrests.

The problem the field workers faced was not simply a few unscrupulous businessmen, but the entire system. When New Deal legislation brought sweeping protections to American workers in the 1930s (unemployment insurance, regulation of hours and wages, age requirements and protection of unionization efforts), field laborers had been specifically excluded. This allowed the agriculture business model to be structured on a presumption of cheap labor provided by workers who were treated more like farm equipment than people.

“Agribusiness in California has developed on cheap labor—and not by accident; it’s been planned,” Mr. Chavez once told an interviewer. “To maintain cheap labor the growers have worked out a horrible system of surplus labor—a surplus labor pool that they are experts at maintaining.”

The interests of agribusiness were interwoven with banks, government agencies and local law enforcement. Grower-maintained farm organizations set wage terms without the involvement of workers and made sure surplus workers were always available. Labor contractors on both sides of the border were a key component of the system and cooperated in the exploitation. Mr. Chavez believed this system, although legal, was profoundly unjust. He insisted that it violated the human dignity of all of those involved, growers and workers alike.

Many of the campesinos the labor organizer visited in mid-1962 told him a union was an impossible goal. There was too much—money, law and history—working against him. He was undaunted. Six months after he turned 35, at a fall gathering of 232 farm workers in Fresno, Calif., the National Farm Workers Association was born. (September 30, 2012, marks the group’s 50th anniversary.)

The association was off to a good start three years after it was formed. Members had a credit union, an auto repair co-operative, burial insurance and a newspaper. Cesar Chavez knew it would take several more years of intense organization and fundraising before his organization could mount a strike. But the N.F.W.A. was not afforded that time. On Sept. 8, 1965, members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, another new organization founded by the A.F.L.-C.I.O. in 1960, began a strike from the grape fields of Delano, Calif., with little enthusiasm or funding. The N.F.W.A. could either watch from the sidelines or join the fight; after intense deliberation, Mr. Chavez chose the latter.

The Delano grape strike lasted for five years and included two years of organized grape boycotts in major cities throughout the country. The N.F.W.A. and the A.W.O.C. merged to become the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, headed by Cesar Chavez. (In 1972, with a charter from the A.F.L.-C.I.O., the committee became the United Farm Workers of America).

California’s Gov. Ronald Reagan defiantly consumed grapes and called the strikers “barbarians.” He ordered state agencies to send welfare recipients and prison inmates to replace striking workers, a move the California State Supreme Court later struck down. President Richard Nixon appeared on camera, like Reagan, eating grapes. And in 1969, the U.S. Department of Defense bought three million pounds of grapes more than in the previous year to counter the boycott’s effect.

Finally, in July 1970, triumph came. The collective bargaining contracts signed were the very first in U.S. history between growers and a farm labor union. With them came the hiring hall (to eliminate the capricious and unfair hiring and firing practices common until then), bathrooms, drinking water, fixed hours and overtime. In 1975 the landmark Agricultural Labor Relations Act codified collective bargaining rights for California’s farmworkers.

Rooted in Faith

The story of the following 25 years is rich and complex. Alongside inspiring successes, courage and faith, there were also real failures and shortcomings as a leader and a Christian. These include a leadership style marked by suspicion of disloyalty by those with whom he worked closest, a deep need for an enemy to battle and insistence on micromanaging daily U.F.W. business.

Until his death in 1993, Mr. Chavez worked to help business owners, politicians and workers themselves grasp that campesinos were endowed with the same human dignity as every other person, a dignity laws and business policies must reflect. He also insisted that advocacy on behalf of farmworkers had to be nonviolent.

The convictions that supported Mr. Chavez’s brave actions did not spring from a general sense of moral rectitude. They were rooted in his Catholic faith, passed on to him and his siblings in childhood by their mother and learned more deliberately in adulthood through his study of Catholic social teaching. Around 1950, Chavez had come under the influence of San Francisco-based missionary, the Rev. Donald McDonnell. The priest had explained to him the broader economics of California agribusiness and much more.

“That’s when I started reading the encyclicals, St. Francis and Gandhi and having the case for social justice explained,” Cesar Chavez later said of that time. By “the encyclicals,” he meant the major documents of modern Catholic social teaching: Pope Leo XIII’s “Rerum Novarum” (1891) and Pius XI’s “Quadragesimo Anno” (1931). In the former, Leo had in the midst of the Industrial Revolution taken a strong stand for the rights and dignity of the common worker; in the latter, Pius, during the Great Depression, called for a radical restructuring of the capitalist system.

Besides reflecting the teaching of these documents, Mr. Chavez’s work during the following decades anticipated and echoed themes being developed in further social encyclicals by Popes Paul VI and John Paul II. Mr. Chavez’s life became a living illustration of the key ideas they proposed, especially the importance of human solidarity, the church’s “preferential option for the poor” and the call to confront the “structures of sin” built into culture and law.

But Cesar Chavez’s Catholicism was about more than social justice. It was profoundly Christ-centered, in a way that saw Jesus as both the motivation for the work and present in the suffering he sought to relieve. “I think Christ taught us to go and do something,” he said. “We can look at his sermon, and it’s very plain what he wants us to do: clothe the naked, feed the hungry and give water to the thirsty. It’s very simple stuff.” He once spoke of the long hours of work involved in thinning acres of lettuce as “just like being nailed to a cross.”

To the chagrin of many, even among his close associates and supporters, he did not hesitate to incorporate his faith into the activities and mission of the United Farm Workers. The Eucharist was a central expression of this spirituality, and its fundamental form of nourishment. Cesar Chavez went to Mass almost every day. For decades under his leadership, the celebration of Mass was a common element of the union’s demonstrations, as well as part of his personal activities and fasts.

A strong devotion to Mary, under the title Our Lady of Guadalupe, also nourished his faith and that of many Chicano fieldworkers. Banners of La Moreñita led the first marches, adorned altars and dotted prayer vigils. Marian devotion is expressed in the name Mr. Chavez chose for the union’s new national headquarters in Keene, Calif.: Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz (commonly known as La Paz). This devotion to Mary was complemented by warm acquaintance with other saints, including Francis of Assisi and Martin de Porres.

‘¡Sí, Se Puede!’

Fasting is another spiritual practice that played an important role in Cesar Chavez’s spiritual life and work. Short fasts on various occasions were frequent. Three major fasts punctuated his 30 years as head of the U.F.W.: a 25-day fast in 1968, a 24-day fast in 1972, and a 36-day fast in 1988. Each fast included daily Mass for him and his supporters, and each fast ended in the context of the Eucharist. Mr. Chavez made clear that he undertook fasting first for his own personal good and secondarily for the good of the union.

Cesar Chavez modeled an authentic integration of important elements of Catholic faith and life that is rarely seen today. Many Catholics today seem to think they must choose either the sacramental, spiritual or devotional aspects of Catholicism or its social aspects—a dichotomy that was as foreign to him as it was to his friend Dorothy Day. To both of them, these different elements depended upon and nourished each other.

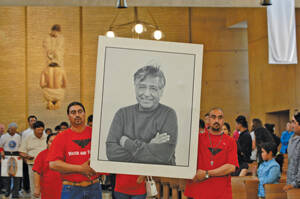

Cesar Chavez died on the road, defending the U.F.W. against a grower’s lawsuit in San Luis, Ariz., on April 23, 1993, not far from the small family farm in the Gila River Valley where he was born. He is remembered on his birthday, March 31, with state holidays in California, Colorado and Texas. Today, the U.F.W. continues its work on behalf of American field laborers, though in far smaller numbers and with diminished strength compared with its heyday. This is partly a result of an internal power struggle that arose from Cesar Chavez’s late-in-life failures in leading the organization. Still, his example has strengthened and inspired millions who work for social justice on various fronts in the United States and abroad. Four years ago, presidential candidate Barack Obama borrowed as one of his major campaign themes the U.F.W. slogan “¡Sí, Se Puede!” (“Yes, We Can”).

It is a legacy that runs dramatically counter to the notion of religion as an opiate of the masses. “I don’t think that I could base my will to struggle on cold economics or on some political doctrine,” Cesar Chavez said. “I don’t think there would be enough to sustain me. For me the base must be faith.”