Christ did not come into the world to die for gold.

—Bartolomé de las Casas

Who is my neighbor? That question emerges as one of the critical questions of the Gospels. After all, as Jesus confirms to an inquiring scribe, our eternal life rests on loving God and our neighbor as ourselves. And so the scribe’s question, “Who is my neighbor?” could not be more pertinent. Jesus answers by way of the parable of the Good Samaritan. In so doing, he cuts through any easy notion that our “neighbor” is simply the person who lives next door or who lives in the same “neighborhood,” who looks like us or shares our values.

The story of Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), a Dominican friar and one of the first Europeans to set foot in this hemisphere, offers another answer to the question. His story raises the further question: Who are those in our world who “don’t count,” whose humanity does not measure up, whose aspirations and needs are not our concern? How would we respond, how would we organize our lives if we believed our salvation rested on the answer to that question?

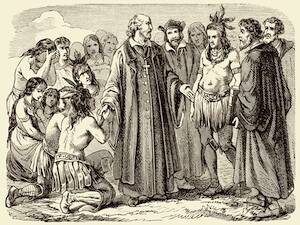

The arrival of three small Spanish ships on the blue shores of the Bahamas in 1492 marked the beginning of an unprecedented collision of cultures. For the Spanish explorers and their royal patrons, the “discovery” of “the new world” was like the opening of a treasure chest. But for the indigenous peoples, whom Columbus called Indians, it marked the onset of oblivion. For most of the invaders, this was not a serious consideration. In their view, the Indians were a primitive, lesser breed; as Aristotle taught, some people were born to be slaves and others to be masters. While the church endorsed the conquest as an opportunity to extend the Gospel, there were few theologians of the time prepared to see the Indians as fully human and equal in the eyes of God. One who did was the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, who was so affected by what he had seen during the early decades of the conquest that he devoted his long life to raising an outcry and bearing witness before an indifferent world.

Gilded Cruelty

To an extraordinary degree the life of las Casas was bound to the fate of the Indians. As a boy of 8, he witnessed the return of Columbus to Seville after his first voyage to the New World. With fascination the young boy watched as the Admiral of the Ocean paraded through the streets, accompanied by seven Taino Indians (the surviving remnant of a larger number who began the voyage). As he recalled, they carried “very beautiful, red-tinged green parrots,” as well as jewels and gold “and many other things never before seen or heard of in Spain.”

His father quickly signed up for Columbus’s second voyage, and in 1502 Bartolomé made his first trip to Hispaniola (currently Haiti and the Dominican Republic). After later studies in Rome for the priesthood he returned to the New World, where he served as chaplain in the Spanish conquest of Cuba. Though a priest, he also benefited from the conquest as the owner of an encomienda, a plantation with Indian indentured laborers.

In these years, he witnessed scenes of diabolical cruelty, which he later chronicled with exacting detail. He described how the armored Spaniards would pacify a village by initiating massacres; how they would enslave their captives and punish any who rebelled by cutting off their hands; how they would consign them to die before their time through overwork in the mines and plantations. His reports, based, as he frequently noted, on “what I have seen,” included accounts of soldiers suddenly drawing their swords “to rip open the bellies” of men, women, children and old folk, “all of whom were seated, off guard and frightened,” so that “within two credos, not a man of all of them there remained alive.”

Such scenes, replayed constantly in his memory, haunted las Casas for the rest of his life. They also began a process of conversion, as the Spanish priest gradually defected from the cause of his own countrymen and identified with those who were treated as nonpersons, of no account, of “less worth than the dung in the street.”

In 1514, las Casas, 30, gave up his lands and the Indians in his possession and declared that he would refuse absolution to any Christian who would not do the same. Eventually, he joined the Dominican order and went on to become a passionate and prophetic defender of the indigenous peoples. For more than 50 years he traveled back and forth between the New World and the court of Spain, attempting through his books, letters and preaching to expose the cruelties of the conquest, whose very legitimacy, and not merely excesses, he disavowed.

On one occasion, a bishop became bored with the Dominican’s account of the death of 7,000 children and interrupted him to ask, “What is that to me and to the king?” With fierce indignation, las Casas replied, “What is it to your lordship and to the king that those souls die? Oh, great and eternal God! Who is there to whom that is something?” To las Casas the Indians were fellow human beings, subject to the same sadness, entitled to the same respect. With this insight it followed that every ounce of gold extracted by their labor was theft; every indignity imposed on them was a crime; every death—whatever the circumstances—was an act of murder.

Although the main attraction for the Spanish in the New World was gold, the conquest was ostensibly justified by evangelical motivations. The pope had authorized the subjugation of the Indian populations for the purpose of implanting the Gospel and securing their salvation. Las Casas claimed that the deeds of the conquistadors revealed their true religion: “In order to gild a very cruel and harsh tyranny that destroys so many villages and people, solely for the sake of satisfying the greed of men and giving them gold, the latter, who themselves do not know the faith, use the pretext of teaching it to others and thereby deliver up the innocent in order to extract from their blood the wealth which these men regard as their god.”

Scenes of the Crucified Christ

With shame, he recounted the story of an Indian prince in Cuba who was burned alive. As he was tied to a stake a Franciscan friar spoke to him of God and asked him whether he would like to go to heaven and there enjoy glory and eternal rest. When the prince asked whether Christians also went to heaven and was assured that this was so, he replied without further thought that he did not wish to go there, “but rather to hell so as not to be where Spaniards were.” las Casas notes with bitter irony, “This is the renown and honor that God and our faith have acquired by means of the Christians who have gone to the Indies.”

But las Casas’ theological insights went far beyond a simple affirmation of the Indians’ human dignity. In their sufferings, he argued, the Indians truly represented the crucified Christ. So he wrote, “I leave in the Indies Jesus Christ, our God, scourged and afflicted and beaten and crucified not once, but thousands of times.”

For las Casas there could be no salvation in Jesus Christ apart from social justice. Thus, the question was not whether the Indians were to be “saved’’; the more serious question was the salvation of the Spanish who were persecuting Christ in his poor. Jesus had said that our eternal fate rests on our treatment of those in need: “I was hungry and you fed me, naked and you clothed me.… Insofar as you have done these things to the least of my brothers and sisters, you have done them to me” (Mt 25:31-40). If the failure to do these things was enough to consign one to hell, what about the situation of the New World, where Christ, in the guise of the Indians, could justly say, “I was clothed, and you stripped me naked, I was well fed, and you starved me.…”?

Las Casas did not oppose the goal of evangelization. But this could never be achieved by force. “The one and only method of teaching men the true religion was established by Divine Providence for the whole world and for all times, that is, by persuading the understanding through reason and by gently attracting or exhorting the will.” Needless to say, such views on religious freedom, the rights of conscience and the relation between salvation and social justice were far advanced for his time; indeed, they were scarcely matched in the Catholic Church until the Second Vatican Council. Even then, they were bitterly debated.

Nevertheless, las Casas did win a hearing in Spain, where he was named Protector of the Indians. With the passion of an Old Testament prophet, he proclaimed: “The screams of so much spilled human blood have now reached heaven. The earth can no longer bear such steeping in human blood. The angels of peace and even God, I think, must be weeping. Hell alone rejoices.” But his efforts made little difference.

In 1543, with court officials in Spain eager to be rid of him, las Casas was named a bishop. While he spurned the offer of the rich see of Cuzco in Peru, he accepted the impoverished region of Chiapas in southern Mexico. There he immediately alienated his flock by once again refusing absolution to any Spaniard who would not free his Indian slaves. He was denounced to the Spanish court as a “lunatic” and received numerous death threats. Eventually he resigned his bishopric and returned to Spain, where he felt he could more effectively prosecute his cause. He took part in an epic debate with one of the leading theologians of the day, defending the humanity of the Indians, their right to religious liberty, and challenging the legality of the conquest. He also fought to abolish the encomienda system and wrote voluminous histories of the conquest and “the Destruction of the Indies.” By this time, he charged, the once-vast indigenous population of Hispaniola had been reduced to 200 souls. Las Casas died in his monastic cell on July 18, 1566, at 82, confessing to his brethren his sorrow and shame that he was unable to do more.

Las Casas’ Legacy

Five hundred years after the “discovery” of America, what are we to make of this life, this witness? Clearly for his writings on human equality and his defense of religious freedom, las Casas deserves to be remembered as a political philosopher of high significance in the history of ideas. But in decisively challenging the identification of Christ with the cause of Christendom, he proposed a recalibration of the Gospel that continues to provoke a response. In 1968 the bishops of Latin America, meeting in Medellín, Colombia, examined the social structures of their continent—in many ways, the ongoing legacy of the early conquest—and named this reality as a situation of sin and institutionalized violence. To preach the Gospel in this context necessarily involved entering the world of the poor and engaging in the struggle for justice.

In undertaking such a shift in perspective and allegiance, the bishops were renouncing their age-old identification with the rich and powerful, and their new stance provoked a furious reaction. As Dom Hélder Câmara, a courageous Brazilian bishop cut from similar cloth as las Casas, observed, “When I feed the poor they call me a saint. When I ask why there are so many poor and hungry, they call me a Communist.” In subsequent years many priests, sisters and lay Catholics raised this same question, with fateful consequences. In the words of Oscar Romero, the prophetic archbishop of San Salvador: “One who is committed to the poor must risk the same fate as the poor. And in El Salvador we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, to be tortured, to be captive, and to be found dead.”

In the decades of the 1970s and ’80s, the truth of those words would be played out in the lives of tens of thousands of Christian martyrs in Latin America. They included Archbishop Romero himself, a bishop like las Casas, whose conversion had been prompted by his encounter with the “scourged Christ” of the poor. He was assassinated in 1980 while saying Mass in El Salvador, and he became a symbol of a new church born of the faith and struggle of the poor. His death was a potent sign of the lingering contradictions implied in the original “evangelization” of the Americas—that 500 years after the arrival of Columbus, in a land named for the Savior, a bishop could be assassinated by murderers who called themselves Christians, indeed faithful defenders of Christian values.

Las Casas lived in a time of epochal change, in which new, unprecedented realities posed new questions. Were the Indians truly human? Over time, that question has been definitively answered—at least in theory. But in practice? Slavery in the United States was abolished only 150 years ago, legalized segregation in our own lifetime. But to what extent do we truly consider the lives of those designated the “other” as equal to our own? In a global economy that largely functions to siphon wealth and resources from the world’s poorest to its wealthiest inhabitants, who can say whether it is God or gold that we truly worship? As we steadily ravage the irreplaceable natural resources of the planet and recklessly undermine the fabric of sustainable life on earth—all for the sake of short-term profit—who can say that we have advanced beyond the rapacious conquistadors, whom las Casas depicted as “wolves, tigers, and hungry lions” feasting on the blood of their victims?

Long after the death of las Casas, his writings became the basis of the “Black Legend,” a potent weapon in the service of Protestant anti-Catholicism and anti-Spanish propaganda. In light of the bloodstained history of the past century, it is harder to ascribe his testimony to some peculiar Iberian aberration from the land of the Inquisi-tion. In fact, his writings pose the deepest challenge to the role of the church in our time. In the face of today’s injustice and violence, in the face of all the threats to human survival, do Christians stand on the side of the victims or with those who profit from their suffering? The Jesuit philosopher and theologian Ignacio Ellacuría of El Salvador, who along with Romero would later join the company of martyrs, spoke of the “crucified peoples of history.” Like las Casas with his talk of the “scourged Christ of the Indies,” Ellacuría compared the poor with Yahweh’s Suffering Servant. In their disfigured features he discovered the ongoing presence and passion of Christ—suffering because of the sins of the world. In this light, he said, the task of the Christian was not simply to worship the cross or to contemplate the mystery of suffering, but “to take the crucified down from the cross”—to join them in compassion and effective solidarity.

Five centuries before the phrase was coined, las Casas’ “preferential option for the poor” continues to trouble the conscience of all who turn their gaze from the sufferings of the “other,” whether in our midst or across the sea, while daring to ask, “What is that to me?”

My point is that this man did his best. Each of us has, in our own circumstances, a similar opportunity every day. With prayer, grace and vigor, we can do His Will. Bartolomé de las Casas did, and his example can inspire us.

Thank you Mr. Ellsberg!

In a global economy that largely functions to siphon wealth and resources from the world’s poorest to its wealthiest inhabitants, who can say whether it is God or gold that we truly worship? "

is unsupported and is an unacceptable condemnation of a majority of people who are working hard to create more wealth to be shared by all.