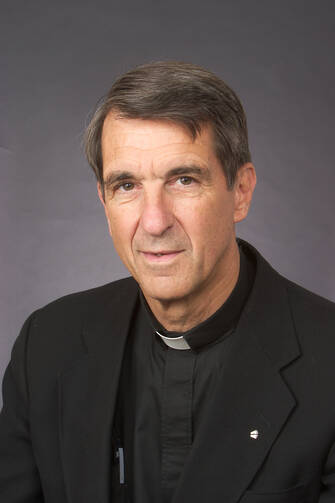

Joseph D. Fessio, S.J., is the founder and editor of Ignatius Press in San Francisco. A graduate of Bellarmine Prep in San Jose, he studied civil engineering at Santa Clara University for three years before entering the Society of Jesus in 1961. He holds a Th.D. in theology from the University of Regensburg, where then-Father Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) directed his thesis on the ecclesiology of Hans Urs von Balthasar.

Father Fessio taught philosophy at Santa Clara University from 1967 to 1969. From 1974 to 1998, he taught systematic and spiritual theology at the University of San Francisco before serving in a variety of administrative capacities at Ave Maria University from 2002 to 2009. He founded the Saint Ignatius Institute at U.S.F. in 1976 and Ignatius Press in 1978. Both before and after Pope Benedict XVI was elected in 2005, Ignatius Press has been the primary English-language publisher of his pre-papal writings.

On July 26 at World Youth Day 2016 in Krakow, Pope Francis officially released the Docat, a youth catechism on Catholic social teaching collecting various magisterial and papal documents. Following up on the Youcat released by Pope Benedict XVI at World Youth Day in 2012, Ignatius Press was once again selected as one of several international publishers for the Docat, and Father Fessio served as an editor on the English-language edition. On Aug. 18, I interviewed him by email about this book.

What inspired Pope Francis to publish a youth catechism on Catholic social teaching and how did you get involved?

Actually, if Pope Francis was inspired, it was post factum. Docat had already been planned, and the writing had begun, before his election to the papacy. However, it is certainly a happy providence that the Docat aligned so well with his interests and priorities.

My involvement in the Youcat and now the Docat has an odd pre-history. Cardinal Christoph Schönborn and I have been friends since we lived together in the Schottenkolleg (at the time the diocesan seminary) in Regensburg in 1973-74 as students of then-Professor Ratzinger. In the 1990s he asked for my help in the English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. After the publication of the Catechism he was making a presentation in his Archdiocese of Vienna and during the Q&A period a woman stood up and said, in so many words, “This is wonderful. But it’s for adults. What about the children? They need a catechism too.”

Cardinal Schönborn responded by agreeing with her, but saying it needed to be a catechism not only for but also with the participation of young people. The woman organized two summer youth programs to work on adapting the Catechism for young people. She was joined by Bernhard Meuser, a German editor and youth catechist. From this the Youcat was born.

How did Ignatius Press become English-language publisher of the Youcat and now the Docat?

When Bernhard contacted me to see if Ignatius Press would be interested in being the publisher of the worldwide English edition, I assumed it was because of Cardinal Schönborn. That was not the case.

I had been invited to give a talk in Torun, Poland, and while I was there I was interviewed by a journalist working for a German Catholic magazine called Vatikan. He asked me about the origins of Ignatius Press. I explained that during my theology studies in Europe I had not only made the acquaintance of theologians like de Lubac, von Balthasar, Bouyer and Ratzinger but also for the first time had begun drinking wine (in France) and beer (in Bavaria).

Upon my return to the United States, I had my first taste of American beer. I spat it out and said, “If this is going to be called beer, I need another name for what I drank in Bavaria.” (This was in the days before the microbrewery revolution.) Later, as I was giving a retreat and quoting de Lubac, Balthasar, et al., a sister asked me if there were any great American theologians. I told her the beer story and said that while there were some very good theologians in the United States (I mentioned Avery Dulles, of course), still, if we were going to call them theologians, we needed another name for the giants I had studied in Europe.

I concluded the interview by saying that Ignatius Press was founded in 1979 so that the writings of these theologians could be accessible to an English-speaking readership.

Bernhard Meuser told me later that when he read that article and the reference to Bavarian beer, he decided he wanted Ignatius Press to be the English publisher of the Youcat. In vino veritas, sed in cervisia opportunitas!

What was your impression of Pope Francis’ attitude toward this project and how did your personal collaboration on it unfold?

Pope Francis, of course, has a great appreciation and respect for Cardinal Schönborn who had explained the project to him. The pope was not only supportive but enthusiastic and readily agreed to write the introduction to Docat just as Pope Benedict had done for Youcat.

As for my collaboration, well, my German was never that good and has not gotten any better. But it was sufficient for me to review the English translation, compare it with the German original where necessary, and even catch a few ambiguous statements in the original that needed to be and were corrected.

Ignatius Press published the English version of the Youcat in 2012 and I have to say my freshmen theology students liked it quite a bit when we used it at Jesuit High School in Tampa. From your perspective as English-language publisher, how has the Youcat been received in the United States and elsewhere so far?

Well, from my perspective as a priest and educator, I am delighted that it has helped so many young people, their parents and catechists. As a publisher, I’m quite content—we’ve sold 800,000 copies!

You’ve also published companion books and other materials for the Youcat. What is it about the style of these new youth catechisms that makes them so appealing to teachers and students?

To me the most important and effective factor in developing the Youcat was the direct and energetic participation of so many young people. They not only contributed photographs they had taken and quotations from favorite authors and celebrities—this became part of the sidebars and illustrations—but they worked with parents and catechists, asking the questions they wanted answers to, carefully reading the whole Catechism to look for answers, and then helping to express the answers in language meaningful to their peers.

How is the Docat a successor to the Youcat in spirit and content?

The spirit, the collaboration of young people, and the appealing language and graphics are just like the Youcat. But the Docat focuses on the church’s social teaching and expands the Youcat’s treatment of it.

Where did you get the acronym “Docat” and what does it stand for?

It’s from the Germans, whose popular culture includes a lot of borrowings from the United States. Youcat was a contraction for “Youth Catechism.” (Sounds much more appealing to young Germans—and everyone else—than Jugendkatechismus.) Docat is a back formation from Youcat: “Do” (as in moral and social obligations) and “Catechism.”

What does Catholic social teaching mean to you and why should young people care about it?

“Catholic” means not only “universal” but, even more fundamentally, and etymologically, “according to the whole” or “organic and integrated.” The Torah came on two tablets: three commandments related to God; seven related to neighbor. And Jesus responded to the question about the “greatest commandment in the Law” with a twofold answer: Love of God with one’s whole heart and love of neighbor as oneself.

Catholic social teaching is an integral part of total Catholic teaching and if Jesus is to be trusted, no one who ignores it is going to enter the Kingdom. So we have to strive to live it ourselves and communicate it to the next generation.

What is the message of this catechism?

Do good and avoid evil. With a little more detail and practical help, of course.

How do you foresee the Docat becoming a social justice resource for U.S. Catholics?

There has been a renaissance in catechesis in the last couple of decades. The laity especially have contributed increasingly to what was in former times mainly the province of sisters and priests. The bishops have taken their responsibility very seriously and the approval process for catechetical materials has been expanded and refined. As a result there are many more solid resources available for catechists than was the case in the immediate post-conciliar years.

I don’t think the Docat can or should replace what is already out there. But it can be a very useful complementary resource. I would liken its value to that of the Catechism for adults. (And, by the way, we’ve found that a lot of adults who find the Catechism pretty heavy going have very much appreciated the Youcat.) It’s a resource that every young person should have, one to which parents, teachers and catechists can refer in their teaching.

What is distinctive about this catechism that sets it apart from other catechisms for young people?

The Holy Father has given it his personal and enthusiastic recommendation. As he says in his Introduction: “I wish I had a million young Christians or, even better, a whole generation who are for their contemporaries ‘walking, talking social doctrine.’” The Docat is part of a worldwide movement of young people continuing the spirit of the World Youth Days in an ongoing way, preparing themselves and being evangelists to their peers.

Sean Salai, S.J., is a contributing writer at America.

Thank you all for reading. Let's pray for the success of the new social justice youth catechism -- the Docat -- that Pope Francis has promulgated and that Ignatius Press is now publishing in the U.S. And let's pray for the healing of broken relationships in our world.

"The devil has two weapons: the main one is division, the other is money" (Pope Francis to new bishops 09/09/2016 The Pope's App)

Father Fessio's analogy is unfortunate and sad. Give him a chance to explain himself.