For Marissa Nichols, the turning point came one night in 2011 when her husband went out to buy milk. Sitting in their apartment in Santa Clara, Calif., with her then 2-year-old daughter and infant son, she felt profoundly alone and in despair. They were feelings that had been growing since the birth of her second child and were compounded by the fact that the economic crash left her family in difficult financial circumstances. Nichols had recently quit her job to care for her children at the same time that her husband was transitioning from working as a teacher to training to become a police officer, which meant nights and weekends at the police academy.

The sole caretaker for much of the day, Nichols began to feel burned out and overwhelmed by daily tasks—trying to breastfeed her infant while also feeding a toddler or doing laundry at the coin-operated laundromat nearby. Her discouragement grew into dislike, which grew into what she describes as a “delirious, desperate hatred.” She constantly felt frenzied and then would “stop, break down, and wake up and do everything again.” She found herself taking out her anger on her husband, and the two fought often. Nichols occasionally texted her sister for support, but the days continued to engulf her.

She longed for her family life to mirror “this glorious covenant between God and his church,” with children as “this great fruit of our love.” Instead, she found herself thinking: No, I don’t want “fruit” anymore. I just want everyone to leave me alone. “I just couldn’t bring myself to love anyone or anything,” she said. “I had nothing to rely on, and I didn’t see a point in being alive.”

Then, that night her husband left to buy milk, something in his departure triggered a reaction in Nichols. I feel so alone in this, she thought. She called the nonemergency number for the police and told them she was worried she would hurt herself. She was voluntarily placed in an overnight mental health facility and soon was diagnosed with postpartum depression.

American society often expects women to be all things to all people.

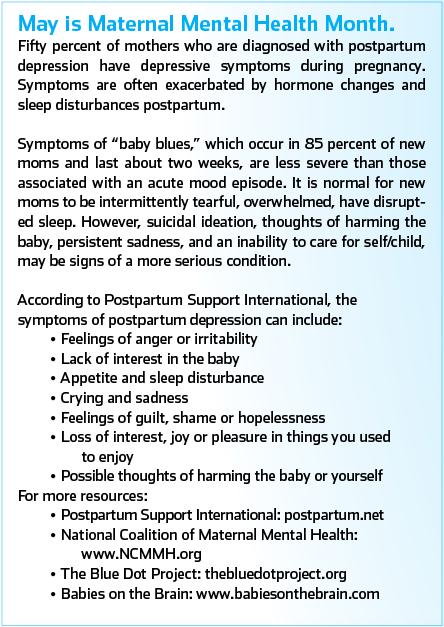

A majority of women experience what is often called the “baby blues”—feelings of sadness and frustration—for about 10 days following childbirth, but these symptoms are typically short-lived. Symptoms that last longer than two weeks can be a sign of a perinatal mood disorder like postpartum depression and anxiety. Approximately one in seven women experience some form of postpartum depression, a medical condition that ranges widely in severity and is marked by persistent feelings of anger, shame, irritability, guilt and an inability to bond with one’s child. The symptoms, often rooted in hormonal or chemical imbalances, can be triggered or compounded by circumstances, including socioeconomic status, prior mental health history and birthing experiences like traumatic delivery, premature birth or trouble breastfeeding. The condition can have a dramatic impact on the well-being of families, increase levels of stress in a marriage and have long-term implications for the health of a child.

Given the complex confluence of factors that contribute to perinatal mood disorders, treatment typically must be multifaceted as well, often including medication, therapy and support groups. Medication often is the first and fastest treatment for depression, but studies have also shown that religious beliefs and practices can be additional helpful tools for coping. According to one study in 2016, women who attended religious services were less likely to experience depression. However, another 2016 study, led by researchers at the State University of New York at Buffalo, found that there is more that churches and faith communities can do to support mothers who have experienced postpartum depression, particularly African-American and Latina women, who are at an increased risk (38 percent) for the condition. The study found that faith communities—especially those in which there are “people who are willing to help and pastors who are willing to listen”—have helped to alleviate postpartum depression symptoms in these women. The researchers suggested greater collaboration between churches and formal service providers could increase the number of women willing to seek treatment.

Despite the potential benefits of a faith community, Catholic women often cannot easily find Catholic resources that can help them to handle the challenges of depression and motherhood. Pope Francis acknowledged this need for practical support for all mothers in his Jan. 7, 2015, general address. “Despite being highly lauded from a symbolic point of view—many poems, many beautiful things said poetically of her—the mother is rarely...helped in daily life, rarely considered central to society in her role,” he said. “Yet the center of the life of the church is the mother of Jesus.”

During the depths of her depression, Nichols—now 35 and a mother of four children between the ages of 9 and 11/2 —turned to her faith, but at first this only made her feel more frustrated. “I went to confession, and I remember being so angry,” she said. “I felt God had completely duped me into this whole thing. I read The Theology of the Body. I believed it. I loved it. I understood natural family planning, but I felt duped into this. I felt: This isn’t anything like what it’s supposed to be like.”

Nichols feels greater peace with her faith today but continues to feel the pressure of an American society that often expects women to be all things to all people, and she continues to hope for more help from the church in finding a healthy balance.

“Society says you need to be able to do it all, and if not, you’re a failure or you’ve wasted your education,” Nichols said. “I don’t need someone to tell me about using my degree or to quote the Catechism to me. How about you come over and help me? I’m a taxi; I’m a cook; I’m a doctor. And people still think, ‘Oh you’re a stay-at-home mom,’ and it’s a strike against me in the world’s eyes, or it’s something the church doesn’t really know how to help with. Our church does so much so well: ministries for the poor, for kids, for prisoners. But there is something that is missing if mothers are feeling this way. There’s something we need to do that we’re not doing.”

Mother of Mercy

For Catholic women experiencing postpartum depression and anxiety, faith and faith communities can be a lifeline—but also a potential source of guilt, shame or frustration. In the same 2015 address, Pope Francis described mothers as “a great treasure,” “the antidote to individualism” and “the greatest enemies of war.” These are welcome and affirming words in many respects, but for mothers struggling with postpartum depression and anxiety, who may feel disconnected from their role and their children, an idealized version of motherhood can seem impossible to live up to and can exacerbate feelings of isolation and spiritual failure.

Shortly after her oldest daughter was born, Gina Parnaby was brushing her teeth in the bathroom as her husband was putting her daughter to bed. Parnaby’s daughter was fussing, and Parnaby felt that the sound of her daughter crying was boring straight through her brain. If I had a gun, she thought, I’d shoot them and myself. When her husband finished putting their daughter to bed he found Parnaby in a puddle of tears on the floor of the bathroom. “I don’t know what’s going on,” she told him, “but I need help.”

I think Mary does get it. But I don’t think that all of our images of her get it.

Through her employer, a Catholic school, Parnaby, 37, now a mother of three, ages 8, 7 and 3, in Roswell, Ga., had access to a hotline for an employee assistance program that connects individuals with mental health professionals. She soon was diagnosed with postpartum depression. The diagnosis was particularly guilt-inducing for Parnaby because she and her husband had long struggled with infertility. “Because we had prayed so hard and so fervently and so long to just even have this child…I was struggling with ingratitude,” Parnaby said. She now knows that infertility is a condition that, in addition to the obvious hardships, can also increase the chance of developing postpartum depression.

“Our image of motherhood and maternity in the Catholic Church is often this beautiful, peaceful and serene Mary, and that’s not always the reality of motherhood,” Parnaby said. “You feel like there’s something wrong with you if you’re not perfectly happy and glowing as a mother. And that’s part of our church culture but also our American culture, and that’s not healthy.” Parnaby has had a lifelong devotion to Mary, and feeling far from Mary during her depression left Parnaby feeling even more isolated. But as she dug further into Marian spirituality, especially the image of Our Lady of Sorrows, Parnaby found greater comfort. “I think Mary does get it,” she said. “But I don’t think that all of our images of her get it.”

As a teacher, Parnaby has offered talks to her female students about both infertility and postpartum depression, but she also hopes that the church understands that it is not just women who need to be aware of such things. “Pastorally, this needs to be on the radar for clergy,” she said. “If a priest sat down with a family to do baptismal paperwork he could say, ‘How are you feeling? How are you coping? If you need help or assistance, here are resources we can direct you to. And here are some resources for Catholic mothers…. What are the signs of postpartum depression? And how can we help?’”

Greater awareness of perinatal mood disorders among Catholic women also could help to dispel the stigma many women feel when trying to discuss their condition with others. Sara Snapp, 32, from Colorado Springs, Colo., experienced postpartum depression after the births of both her children, now ages 8 and 21/2. She had trouble bonding with her children and sought comfort in her faith and in her faith community. However, when she tried to bring up the topic in a mom’s group at her parish, she was met, she said, “with crickets.” She never heard the topic discussed at Mass or at her parish. She turned to prayer and tried to pray every day.

Because we had prayed so hard and so fervently and so long to just even have this child...I was struggling with ingratitude.

“I used to try to imagine what the Blessed Mother would do, and I just keep thinking she would be more patient than me and experience the fullness of God’s love in a way that I wasn’t able to,” she said. Eventually, Snapp expressed this concern to her doctor. “I told her I felt like a bad Christian because I couldn’t beat depression with the power of prayer. And she said, ‘Would you feel someone was a bad Christian because they needed an appendix removed?’ and I said, ‘No, that’s crazy.’ And she said, ‘Yeah, it is.’”

Over the years, Snapp has grown more comfortable sharing her experience. “We talk about motherhood being a holy vocation, but it is often completely ignored in our community life,” she said. “I would dearly love to see women deacons so women could share their life experiences in a setting where they get a little respect. To give women the chance to speak to the whole congregation would open up a whole new conversation.”

A Continuum of Care

Of course, the potential for Catholic postpartum support extends beyond the walls of the church. Catholic physicians and hospitals have the potential to be crucial points of contact for mothers in need. Dr. Marguerite Duane, a family physician in Washington, D.C., and an adjunct associate professor at Georgetown University, worked for several years at a faith-based community health center where she helped to deliver about 300 babies in five years. Duane has found that her role as a family physician has allowed her to gain a better understanding of her patients’ lives before, during and after pregnancy, giving her a better chance of identifying problems postpartum.

“It’s not just that I see patients a few times, but that I formed a relationship with them,” she said. “I got to understand what was normal for them and what wasn’t.”

As co-founder of the Fertility Appreciation Collaborative to Teach the Science, Dr. Duane also works to educate physicians and health professionals in the basic principles of fertility awareness-based methods of family planning, so physicians can provide better support for families using these methods. For Catholic women who choose these methods, the postpartum period can be a crucial time for support, according to Dr. Duane, as frustration and stress around natural family planning methods are common following a perinatal mood disorder, often due to pressure from either doctors or Catholic communities.

“One of the challenges is you want to treat [the depression or anxiety] but you also want to address the trigger, so in some cases, there is a strong need to postpone another baby,” Dr. Duane said. “And a woman may be under pressure from a well-meaning physician to go on birth control, which may add to the conflict or stress women feel. Some doctors can be dismissive of that, and encouraging a woman to give up an aspect of her faith—which may be part of her healing—can add to the internal conflict and undermine her trust in a method of family planning that can be used very effectively.”

Dr. Duane said that another source of pressure for women struggling with postpartum depression can come from well-intentioned Catholics. “There can be a badge of honor among some people to think that the more kids you have the better Catholic you are,” Dr. Duane said. “But Pope Paul VI did not call for women to have as many children as they can; he said if there are serious reasons for a couple to postpone a pregnancy, they need to use N.F.P. to postpone pregnancy. And for a couple postponing pregnancy in order to deal with postpartum depression, getting comments or criticism from well-meaning Catholic friends asking when they plan to have more children can undermine their experience.”

Supportive and understanding health care professionals can go a long way toward providing a better continuity of care for women. St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, Calif., a member of the Catholic Health Alliance, delivers about 5,000 babies per year. The hospital makes sure that each mother is screened using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, a 10-question form that assesses a mother’s risk for postpartum depression. Katie Monarch is a therapist and the founder of the hospital’s program Caring for Women With Maternal Depression. In her 11 years at the hospital, Katie has worked with over 2,000 moms. While the Edinburgh test is a well known and effective predictor of depression, she estimates that only about 50 percent of hospitals consistently screen women for perinatal mood disorders.

The success of St. Joseph’s program comes in part from their ongoing relationship with patients and a flexibility that accounts for a woman’s individual situation. Women can be screened in the hospital after delivery, but the topic is also discussed in prenatal birthing classes, and brochures about the condition are placed in referring obstetrician offices. New moms return to the hospital’s mother-baby assessment center three days after the birth, a process that allows for relationship building and ongoing care. “The Edinburgh paperwork puts the seed in [a new mom’s] head that ‘If I am having problems I know they have a program and I know that I can call them,’” Monarch said. “And a lot of moms have called because of that.”

In recent years, Monarch said, the topic of postpartum depression has received greater attention as celebrities have spoken out about their own experiences with it. She cited Chrissy Teigen’s recent essay about her postpartum struggle in Glamour. “You see Chrissy at all the awards looking stunning, and with that baby that is as cute as a button, and she says ‘I’m not liking this and it’s hard,’” Monarch said. “I think that’s perfect. It’s helpful. That normalizes a lot. And these moms are dying to feel normal.”

Postpartum Potential

Despite increasing awareness of the condition, only about 20 percent of women who exhibit symptoms seek help for postpartum depression. This can be attributed, in part, to a lack of understanding of the symptoms, inadequate screening and fear of being stigmatized. Faith communities can serve as a missing link between women and mental health services. It is crucial, however, that faith communities seek out struggling mothers, as studies have shown that women who were experiencing depression were less likely to attend religious services. At a time when women might be most in need of a supportive faith community, they often are less likely to be a part of one.

An informal Facebook poll by America of 116 women who had experienced perinatal mood disorders found that 84 percent stated they had not felt supported by their faith communities during their depression. There are no national Catholic ministries specifically for women experiencing perinatal mood disorders, although some dioceses offer counseling services. And there have been some successful one-time projects. In 2007 the New Jersey Catholic Conference partnered with the statewide Maternal and Child Consortia to train clergy, religious and lay parish staff in the symptoms of postpartum depression.

Jennifer Ruggiero, director of the Respect for Life office of the Diocese of Metuchen, served as the diocesan liaison with the consortium and helped to get information out to parishes. She also planned workshops that included a talk about the clinical side of postpartum depression and a witness talk from Sylvia Lasalandra, a prominent Catholic advocate for awareness about postpartum depression. (Lasalandra has written a book about her experience called A Daughter’s Touch.) Ruggiero said that the people in attendance were moved by the talks but that the turnout by parish leaders had not been as robust as she had hoped. “I would be very much in favor of doing it again,” she said. “I would love to see more clergy educated. But we go from issue to issue, and there are so many pressing issues.”

Recognizing that their diocese or faith community may not have the resources or structures in place to provide support, Catholic women who have themselves experienced these conditions have spearheaded ongoing efforts around postpartum depression awareness at the grassroots level.

Looking back now, Beth Gilbert, 57, knows she experienced some form of postpartum depression after the births of the first three of her five children. But it was only after the birth of her third child that she began to understand what was happening and to seek help. An encounter with a woman religious at her parish who was also a counselor helped her to understand more about her postpartum condition. She began counseling. Medication helped, but so did eating healthy foods, exercising, trying to build social networks and trying not to feel guilty about needing a break. “I had to prioritize self-care so I could be a better caregiver to my children,” she said.

Then, three years after her third child was born, Gilbert had a miscarriage. She found little solace in her parish community. She wrote a letter about her experience with a miscarriage to the pastor at the time, with the hope that it might help him minister to other women who came to the church looking for support. She never received a reply.

Gilbert found comfort in the Mass and sacraments but needed emotional and practical support as well. She sought community at a conference for women in Peoria, Ill., sponsored by the Elizabeth Ministry, an international Catholic organization working to provide spiritual and emotional support and resources to women with regard to childbirth and relationships. Gilbert began talking with other women about the possibility of starting a chapter at their parish. “I thought, Boy, this wasn’t available when I was going through difficult times, and this could be helpful to other people who might experience something similar,” she said.

Postpartum depression is not the main focus of the Elizabeth Ministry, but its model can easily be adapted to include support for mothers struggling with the condition. The ministry at Gilbert’s parish involved personal outreach to women, particularly mothers, in the parish and the community who might need a listening ear or logistical support after a birth or miscarriage or while going through any difficult time. The group worked to match up individuals who had had similar experiences. They started sponsoring pregnancy blessings at the parish four times a year, which had the benefit of identifying new moms so that they could be connected with women in the community if they needed support. They offered prayer cards and baby showers and made calls and visits to each other and delivered meals to new moms.

The support she offered to others through this ministry allowed Gilbert to use her own painful experiences to offer compassionate listening and helped her to gain perspective. “I just needed to be able to find the right balance of taking care of myself and taking care of my children,” she said. “And I needed other people to help me learn to do that correctly. I also had to be an instrument to help create a structure so that other people could benefit.”

Creating a Caring Community

The Blue Dot Project is another resource for women with perinatal mood disorders that came from a mother who sought a supportive community following her experience. Peggy Nosti of Escondido, Calif., co-founded the project after she was diagnosed with postpartum anxiety following the birth of her third child in 2010 at the age of 39. While she was struggling with anxiety, her friends and family took night shifts with the baby, visited her and dropped off meals. Nosti was open about her struggles, but her family members still were careful not to publicly discuss Nosti’s anxiety because they felt she would be embarrassed or ashamed.

“I never understood that,” she said. “I knew it wasn’t my fault...[it wasn’t the case that] I wasn’t equipped to be a mom. It’s a mental health issue.” She hoped to help others understand this as well.

You do the best you can, but we’re not meant to do this on our own. We’re meant to have community.

The daughter of a former priest and a former nun, Nosti, whose children are 11, 8 and 6, was born into a Catholic family dedicated to service. This spirit of service inspired her to search out new ways to communicate to moms who are suffering to let them know they could talk about their experience. She felt that a universal symbol of awareness could help. Nosti then met with a reproductive psychiatrist who agreed to partner with her to found The Blue Dot Project, through which they have promoted their symbol for maternal mental health awareness—the titular blue dot. Postpartum Support International voted the dot the international symbol of the cause, and The Blue Dot Project distributes round baby blue magnets, stickers and pins that can be worn or posted as a sign of support for maternal mental health.

Already the dot magnet on her car has spurred several conversations for Nosti while out in the community. “You do the best you can, but we’re not meant to do this on our own,” she said. “We’re meant to have community.”

Jena Booher, 30, of Chappaqua, N.Y., also channeled her postpartum experience into an effort to help women find community, consolation and balance after childbirth. In contrast to The Blue Dot Project, the main goal of which is to raise awareness, Booher has dedicated her efforts to providing mental health counseling services and consulting services for corporations hoping to provide a family-friendly environment.

Booher spent her pregnancy struggling with hyperemesis gravida, an extreme form of nausea. She also faced a difficult situation at her Wall Street office, in which she was increasingly sidelined from her accounts after announcing her pregnancy. Following the birth of her daughter Siena, now 21/2, complications continued. Booher quit her job shortly after her maternity leave but struggled with processing what her new role as a mother meant for her identity after so many years focused on her career. Booher found herself losing weight and became dangerously thin, partly because she was skipping meals, though she hardly realized she was doing this. She had persistent low energy and insomnia and often ruminated on the tasks she hadn’t completed that day. Nearly a year after childbirth, Booher was diagnosed with postpartum depression.

“I had identified my self-worth in my achievements,” she said. “That contributed to my depression because my identity was flipped on its head.” As she struggled, she grew in her appreciation for what it meant to be a parent. “I had viewed the role quality [of motherhood] as not as great as my big-time Wall Street job,” she said. “It pains me to say that because I now know that’s bullshit. Motherhood is the hardest job there is.”

Approximately 46 percent of women do not return to the workplace after childbirth. For some this is a deliberate choice; others have no choice but to leave after facing the cost of child care, inflexible work schedules, the wage gap, lack of maternity leave or discrimination. Booher set out to eliminate some of these factors by founding Babies on the Brain, a cross-sector organization that both helps new moms transition to their new identities through life-coaching services and counseling and helps companies set policies that make it easier for women to stay in the workforce. “I help companies think beyond nice-looking maternity leave policies,” she said. “It’s about redefining the status quo.”

The status quo for Booher’s own life has changed as well. She no longer is bound by 12-hour days at an office, which has helped her to embrace her role as a working mom. “I wanted to work and am working but in a way that is not defined by traditional norms,” she said. “I am the primary caretaker of my daughter, and I’m a full-time grad student, and I’m running my own business. How do I do all that? I work weird hours. I get up at 4:30 or 5 a.m. and do work before my baby wakes up. The rules about how to achieve success—I am not playing that game because that game does not work for moms.”

Struggling with depression and motherhood forced Booher to reconsider her prayer life as well. “I tried to pray a lot with the Annunciation,” she said. “That prayer really helped me. Knowing that Mary didn’t have all the answers, and if Mary didn’t have all the answers then sure as hell I don’t.” For now, she tries to focus on the beauty of the moment, on the moments of “sheer joy” she now can feel about being a mother. “It’s this mystery. The joy I feel that I helped bring this life into the world is an immense, overwhelming, take-your-breath-away feeling, as hard as it is in real life.”

The difficulties of motherhood are something to which Pope Francis has also called attention, in the hopes that the church will pay closer attention as well. “Perhaps mothers, ready to sacrifice so much for their children and often for others as well, ought to be listened to more,” he said. “We should understand more about their daily struggle to be efficient at work and attentive and affectionate in the family.”

These days, Marissa Nichols is still facing the daily struggle that comes with both parenting and depression, but the ways in which she has been able to draw closer to God through her painful postpartum experience have also become clearer. “I’m getting to know God as a parent,” she said. “Humanity does to him what I know my kids do to me.” She also knows that while it still can be difficult to explain depression to others, she feels “no judgment from [God] about this. Just a lot of mercy.”

She hopes that other Catholic women struggling with postpartum depression and anxiety feel this, too, and apply that same mercy to each other, letting go of the stigma and shame too often surrounding these issues. “The church is saying motherhood is something we should all revere,” Nichols said. “But we have yet to fully put that into practice.”

Clearly, women do not expect much in sympathy nor compassion from either the churches or society when they encounter this crisis, comparable to PTSD. For others of my septuagenarian generation, it was common practice for mothers to receive "laying in days" prior to giving birth and an extended hospital stay. My wife gave birth to two of our children at Kaiser Hospital in Sacramento during the 1960's. First, the cost under our Kaiser Plan health insurance was only $30! (that was for the phone in her room). Second, she was held for four days while she healed, bonded with the new baby, and talked and felt continual support from visitors, nursing staff and some "off duty" time for herself. I also remember a rather strict Irish pastor of my parish who had a somewhat secret ministry: on Thursdays of every week, he would visit the maternity ward in our local Catholic hospital and stop to talk with every new mother. If they were Catholic, he would often use the time of his visiting to arrange for a baptism ceremony for the new baby as soon as possible. And of course, the wonderful nursing sisters of that era were constant encouragement, counselors, and sources of spiritual support.

I believe that kinder, gentler time before today's "drive-by" birthing process was the foundation for support for new and repeat mothers. As a body, the "sisterhood" and a few sympathetic pastors helped far more than they ever knew.

Contrast that with today's concerns and attitudes towards women and their needs.

Thanks for writing this article. Husbands should be mindful that Paul, instructing wives to their particular duty, also instructed husbands [b]with equal force and emphasis[/b] to be attentive to the needs of their wives.

Catholic women clearly need more support from the church community and each other with the difficulties of motherhood. The part of this presentation I found most interesting is the beginning of the video, where Booher talks about women not asking for what they need from corporations. It is against the cultural rules of women to ask for things. It might be helpful for the Church to sponsor a conversation about cultural rules. Of course, if women learn the cultural rules of communities, they might ask for a lot more than they get from the Church.

"Yet the center of the life of the church is the mother of Jesus." I agree, yet we keep women out of the sacramental priesthood. Why? Since the Marian dimension of the Church precedes the Petrine dimension (CCC 773), it is hard to see why women cannot be successors of the apostles. If Mary was (among other things) predecessor of the apostles under the Old Law, why is it that women cannot be successors of the apostles under the New Law? Perhaps the Church is suffering from pospartum depression after Pentecost, and cannot see that, for the sacramental economy under the New Law, the masculinity of Jesus is as incidental as the color of his eyes. Now that the patriarchal phase of salvation history is passing away, the ordination of women to the priesthood and the episcopate would be an effective antidepressant. I think we should allow the Lord to call women, and see what happens!