For a place where history was made less than a quarter of a century ago, the room in the offices of the Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas is an unassuming one. Tucked away next to a dark hallway and a quiet courtyard, it features just a coffee table, a few chairs and a sofa.

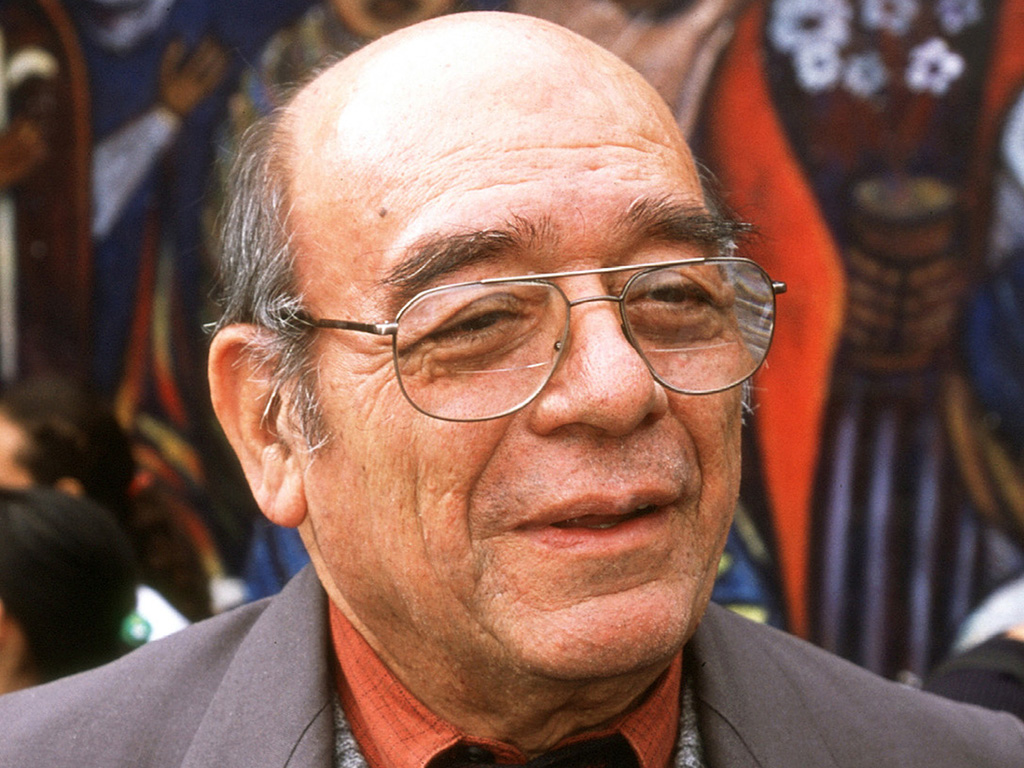

“The furniture here was bought specifically for the negotiations in 1994,” Gonzalo Ituarte Verduzco, a Dominican friar, says. He smiles fondly. “This is where the diocesan negotiators spoke with representatives of the government and the Zapatistas, trying to broker a peace agreement.” The humble space is dominated by a large portrait of Samuel Ruiz García—between 1959 and 1999 the bishop of a diocese that spans the highlands of Mexico’s southernmost Chiapas State and the man who changed Chiapas and the diocese forever.

On Jan. 1, 1994, hundreds of masked and armed soldiers of the indigenous Zapatista Army of National Liberation (E.Z.L.N.), named after the famed agrarian revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, marched into San Cristóbal. It was supposed to be a festive day for Mexico’s political and business elites and President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, the day Mexico entered the North American Free Trade Agreement. Instead, it became the day indigenous Mexicans rose up in arms after centuries of extreme poverty and marginalization.

As Mexican armed forces moved in and conflict began, the warring parties looked for a mediator. They knew there was only one man with the moral authority to broker a peace deal: Samuel Ruiz García. With the bishop heading negotiations, a cease-fire was reached 12 days later, ultimately resulting in the San Andrés peace agreement of 1996.

“The government knew there was no one more trustworthy than Don Samuel, and the Zapatistas could not confide in anyone else,” recalls Father Ituarte, a close friend and collaborator of Bishop Ruiz. “It was a convergence that started the peace process.”

A Pastor’s Legacy

Outside Mexico, Samuel Ruiz is mostly known for his role in the 1994 conflict. Here in Chiapas, however, his legacy is far broader and deeper. Six years after his death, he remains a towering figure in the political and spiritual imagination of Mexico’s poorest state.

During his 40 years as bishop of San Cristóbal, he transformed the diocese into Latin America’s first real “autochthonous church,” true to the principles of the Second Vatican Council and the Second General Conference of the Latin American and Caribbean Bishops at Medellín, Colombia, in 1968, two events in contemporary church history that influenced him deeply. He preached “evangelization by the poor,” instructed his priests to study local indigenous languages and trained hundreds of catechists and deacons.

In his practice, being an autochthonous church meant incorporating indigenous traditions in the church and welcoming the participation of indigenous people in a region whose inhabitants had never been treated as equals by European colonizers and their descendants. Bishop Ruiz ordained hundreds of indigenous deacons and translated the Bible into Tzeltal, one of the many local Mayan dialects.

Beyond church reform, Bishop Ruiz became one of Chiapas’s and Mexico’s principal advocates of social justice and equality. Championing indigenous rights and the struggle against poverty and racism, indigenous chiapanecos came to lovingly nickname him “Tatic,” which means “father” in Tzeltal, a local dialect. Others called him “El Caminante,” “the walker,” because of his constant travels through Chiapas. After he was ordained, he famously visited every community of the diocese riding a mule.

Bishop Ruiz’s social and religious struggle in Chiapas placed him at odds with figures of authority in Mexican politics. Mexico’s federal government accused him of espousing Marxism and fomenting the revolutionary thought that ultimately led to the E.Z.L.N.’s uprising. Landowners and the rich elites of Chiapas accused him of Communist sympathies and confronted him, sometimes violently.

He was also often at odds with members of the Mexican church hierarchy, who acted as defenders of the political and cultural status quo, and with the Vatican, which did not approve of his ordinations of indigenous deacons. In 1993, he was asked to step down. After he wrote a pastoral letter defending his reforms and his pastoral approach, Mexican bishops rallied behind him, and he would stay on for another six years.

Bishop Ruiz died in 2011 in Querétaro, near Mexico City, after leaving the Chiapas Diocese in 2000. Some of his most important reforms were contested; the Vatican banned the ordination of indigenous deacons soon after his resignation. In a February 2002 letter to Bishop Ruiz’s successor, Felipe Arizmendi, the Vatican stated it feared indigenous deacons would deviate too far from traditional church doctrine and that the liberal interpretation of the responsibilities of deacons and their wives would be a poor example to other indigenous dioceses across the globe. Some feared the married deacons were a first step toward a married priesthood.

But in death, Bishop Ruiz found a powerful ally in Pope Francis, who not only overturned the ban, but last year prayed at Bishop Ruiz’s tomb and celebrated Mass in San Cristóbal with thousands of chiapanecos.

Bishop Ruiz’s legacy looms large in Chiapas. The state has seen some success in relieving poverty and reducing inequality, but in 2017 it still remains one of Mexico’s poorest states. Contemporary disciples like Raúl Vera, now bishop of Saltillo, in northern Mexico, apply similar pastoral methods for combating poverty and defending human rights. And in the recent Nobel Peace Prize nomination of Alejandro Solalinde, a priest famed for fighting for the rights of migrants, the spirit of Bishop Ruiz lives on.

Extraordinary Joy

“Don Samuel was a leader who walked amidst other people, not in front of them,” recalls Father Ituarte. The current provincial of the Dominican order in Mexico, Father Ituarte had worked closely with Bishop Ruiz since he first arrived in Chiapas in 1977, at that time traveling to the state as a tourist. He still fondly remembers his first impressions of the bishop.

“I was a traveling to Ocosingo, a town in the highlands of Chiapas, to the house of the Dominicans. Don Samuel happened to be [going] there at the same time, and I flew with him to Ocosingo in a small airplane,” he says. “There was a great number of people waiting for him, more than a thousand, if I recall, and they received him with extraordinary joy. He was very close to the people there. He was the first bishop I ever met, and he appeared to be a man of the people. I was very surprised, because in 1977 he was still not as visible as he would later be.”

Father Ituarte decided to stay in Chiapas and was ordained a priest soon afterward. From 1989 onward, he would collaborate closely with Bishop Ruiz as the diocese’s general vicar and later the vicar for justice and peace. The two men became good friends.

“I remember him mostly for his clarity of thought and his simplicity,” Father Ituarte says. “He was a man of horizontal relations, never claiming any kind of superiority. What I found astounding was the amount of respect he had for everyone, including those who opposed him. As bishop, he was slandered, insulted, attacked, but he could never bring himself to talk badly about anyone, not even in private.”

When he first arrived in Chiapas, Bishop Ruiz was was not yet the towering figure of social justice he would later become. The first-born son of poor parents in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato, he grew up in a staunchly conservative Catholic family environment during a period of turmoil, when devout Catholics engaged in open warfare with Mexico’s then revolutionary and radically anticlerical government, a period known as the Cristero Wars. Enrique Krauze, one of Mexico’s foremost historians, described Bishop Ruiz’s father as sympathetic to the sinarquista movement, a far-right social and political campaign he deemed “deeply Catholic, but [one that] can also legitimately be described, in its racism and exclusivism, as fascist.”

"He was slandered, insulted, attacked, but he could never bring himself to talk badly about anyone."

Growing up and studying at the seminary in León, Guanajuato’s largest city, Bishop Ruiz espoused conservative Catholic thought; that continued when he entered the Colegio Pio Latinoamericano in Rome. León was one of the core regions of the sinarquista movement, which carried significant influence in the local seminary because of its strong opposition to social Catholicism and the separation of church and state (and later to liberation theology).

According to Mr. Krauze, Bishop Ruiz saw sinarquista initially as “a movement that shook things up, a necessary step in the civic and political education of society.” Less than 15 years later, however, much in his thinking had changed. After a five-year stint as the rector of the Seminary of León, he moved to Chiapas as its new bishop, and his conversion to social justice activist and church reformer began.

“When he first came to Chiapas, he saw the servitude of the indigenous to the owners of coffee plantations, who only allowed the peons to work on small patches that were originally indigenous [land]. There was already a movement towards indigenous workers occupying farms in rebellion against the elites,” Father Ituarte says. “Don Samuel saw from the beginning that the condition of the indigenous wasn’t the will of God, but that it was an effect of injustice.”

"Don Samuel saw that the condition of the indigenous wasn’t the will of God, but an effect of injustice."

The awakened social consciousness of Bishop Ruiz was further encouraged by documents emerging from the Second Vatican Council and the Medellín conference, where issues raised during the council were further discussed.

“I always tell people that Don Samuel took the Second Vatican Council seriously, that he believed in it,” Father Ituarte says. “Translating Bibles into indigenous languages and placing them in the center of evangelization was an instruction of the council. He wasn’t the first to do so; Protestants here already worked on translations, but he immediately assumed it as his responsibility.”

“Indian Dog”

Father Ituarte speaks from his office at the diocesan chancery, a striking, colonial building next to the city’s cathedral, one of southern Mexico’s most iconic colonial structures. The colonial center of San Cristóbal, visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists each year, still retains much of its old charm despite European-style coffee houses that now line the ancient colonial plazas and the ubiquitous smartphone shops and internet hotspots.

The city also barely conceals a vast, centuries-old gap between rich and poor. Barefoot indigenous Mayan women dressed in colorful traditional garb roam the streets begging for change while European tourists and white and mestizo Mexicans relax in the traditional community’s modern restaurants and coffee shops.

In the late 1950s the state was still a semi-feudal region, divided among powerful landowners who ruled their coffee plantations as fiefs, much as their colonial ancestors had done in the centuries before Mexico’s independence. The Mexican Revolution of 1910-20, with its agrarian reform and redistribution of land from the powerful ruling elites to the rural poor, had largely missed Chiapas. In the 1950s, indigenous Mayans in San Cristóbal would still step from the sidewalk when they saw a white man, and the racial slur perro indio (“Indian dog”) was commonly used.

On the large coffee plantations on the countryside, most indigenous workers lived as peons in semi-slavery for the ruling elite. Basic services like health care and education were completely out of reach for the state’s poorest, as was participation as equals with the white and mestizo population in the church. Baptism would often be the only real contact the Mayan communities had with Catholicism.

“Ruiz was shocked to see the extreme poverty of the indigenous population here,” says Pedro Arriaga, a Jesuit priest who is the spokesperson for the San Cristóbal diocese. “The first thing he thought when he came here was that all indigenous chiapanecos should wear shoes and should speak Spanish, but that was before he realized how deeply rooted slavery was here.”

Bishop Ruiz almost immediately clashed with the state’s elites, especially local political bosses and plantation owners. When previous bishops visited the diocese’s rural communities, they would spend the night at one of the large estates. Bishop Ruiz broke with that tradition and stayed at the homes of indigenous workers.

“He would tell the finca owners when they offered him coffee, that the coffee was paid for with blood,” says Father Arriaga.

Father Arriaga heads the Jesuit mission in Bachajón, a small town with a significant Tzeltal Mayan population. A rural community of approximately 5,000 inhabitants in the northern jungle region of the state, it is now a three-hour drive from San Cristóbal, but that connection between the state’s major cities is relatively a recent luxury; in the 1970s, a trip to Bachajón from San Cristóbal would take two days on foot.

"When the finca owners offered him coffee, he would tell them that the coffee was paid for with blood."

It was here, in towns like Bachajón, that Bishop Ruiz undertook a massive effort to train thousands of catechists and deacons to serve areas that had few priests. Bishop Ruiz was not satisfied with just translating the Bible into the local languages, he set out to master the languages himself, placing the indigenous traditions squarely at the top of church priorities.

“In terms of his pastoral and liturgical influence, the central theme was how he approached the diaconate,” David Fernández Dávalos, the Jesuit rector of the prestigious Iberoamerican University in Mexico City says. “He began educating married people, men as well as women, in the San Cristóbal diocese to become permanent deacons in local churches. It was a long process, which probably took up to 15 years before the first few deacons could be ordained.”

According to Father Fernández Dávalos, the indigenous deacons became the backbone of the San Cristóbal Diocese. “Nowadays, you can’t understand the workings of the San Cristóbal Diocese without understanding the work of the permanent married deacons, of deacons accompanied by their wives.”

“When I first arrived here in 1967, the training of catechists was already well on its way,” says Father Arriaga. “Students were given courses to read and understand the Bible and reflect on it by a method of questions and answers. The system of catechists and deacons fit in well with the indigenous cultures here.”

Many catechists would later become permanent deacons. That was the experience of 60-year-old Matteo Pérez. An indigenous Mayan whose mother tongue is Tzeltal, he remembers Bishop Ruiz fondly as “Tatic Samuel.”

“Everyone here of my generation still talks about him. He invited us into the church and trained us to take part in the process of evangelization,” he says. “But his influence went much further than teaching us the word of God.”

"His influence went much further than teaching us the word of God."

Indeed, Bishop Ruiz almost instantly set out to create awareness of the extreme poverty and marginalization of the indigenous chiapanecos, but he also took steps to improve their own self-worth. Celebrating Mass in their own languages empowered the state’s impoverished farmers.

“Before Tatic Samuel came, we were never proud of who we were,” Mr. Pérez says. “Many if us didn’t know how to read or write. He promoted education and told us we had to improve our lives.”

Mr. Pérez became a deacon in 1975, one year after Bishop Ruiz organized the first Gathering of the Indigenous in San Cristóbal, the first grassroots conference by and for indigenous people since Europeans arrived in Mexico almost 500 years before. The event is considered an awakening of indigenous conscience in Chiapas, and historians suggest it helped pave the way for the Zapatista uprising 20 years later.

The Zapatistas and Don Samuel

There is no longer an official dialogue between the Zapatistas and the diocese, priests in Chiapas say, but contact with the so-called caracoles (“snails,” so named in reference to the cochlea as a community center that “hears” the pleas of the people), the administrative centers of the E.Z.L.N., continues. Priests often celebrate Mass and provide spiritual services at caracoles. Attempts by America to speak with Zapatista representatives about Bishop Ruiz’s legacy were unsuccessful, but signs of his influence among the members of the former guerrilla army are hard to miss.

In the north of San Cristóbal, the Zapatistas founded the Universidad de la Tierra (“University of the Earth”), which provides so-called revolutionary education, focused on the environment, indigenous emancipation and the relationship between people and the land they inhabit, with the indigenous chiapaneco culture and traditions at its teaching core. In one of the buildings, a shrine is dedicated to the bishop, and his image is often featured in Zapatista mural paintings.

“You can’t talk about the Zapatistas without talking about Don Samuel,” Father Ituarte explains. “He created a degree of consciousness that made the existence of the E.Z.L.N. possible. We didn’t start or support them as an armed group, but we’re conscious that those who started the movement touch upon the same issues as we did.”

The Zapatista uprising ultimately ended in the San Andrés agreements of 1996. The Mexican government and the insurgents agreed upon indigenous autonomy, respect for indigenous heritage and care for the Mayans’ ancestral lands. The conflict was far from over, however, and violence between the army and indigenous groups continued, culminating in the 1997 Acteal massacre.

The massacre, named after the small town of Acteal, took place on Dec. 22, 1997, when a paramilitary group armed by a local political boss killed 45 people. Police refused to intervene. Many describe it as the saddest moment of Bishop Ruiz’s life, as he spent Christmas of that year burying the victims.

“You can’t talk about the Zapatistas without talking about Don Samuel.”

The Zapatista uprising forced the Mexican government to pay more attention to its most impoverished state. In the wake of the armed conflict, new roads were built and most major cities, like the state capital Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Tapachula and San Cristóbal, are now well connected with smaller towns like Bachajón.

Basic services are without a doubt more available now throughout the state, even in harder to reach rural areas and highlands. Moreover, according to the latest yearly “Poverty and Social Neglect” report of Mexico’s federal Social Development Secretariat (Sedesol), Chiapas is no longer the nation’s poorest state, overtaken by Guerrero and neighboring Oaxaca.

Positive as those numbers may be, they are also a bit deceiving. More than 75 percent of chiapanecos still live in poverty, more than 30 percent in extreme poverty. Land disputes and political violence are still rampant and are now joined by a new, potentially far graver problem: drug trafficking and organized crime, often in collusion with local political strongmen.

“We are now facing drug trafficking and far higher levels of corruption,” says the Rev. Marcelo Pérez. A parish priest based in the town of Simojovel, Father Perez also heads the diocese’s social ministry. “Poverty levels haven’t dropped,” and government statements that report otherwise are lies, he says bluntly.

Father Pérez would know; his social work in Bishop Ruiz’s tradition brought him into direct conflict with local strongmen and criminals in 2015. Unknown individuals placed a price on his head, a threat not to be taken lightly in a state where almost 1,500 people were murdered last year.

He attributes many of the problems the state faces now to political corruption and government aid programs. “The communities nowadays are very fragmented, very divided because of politics,” he says. “It’s an economic attack of sorts. Corruption has increased. The politically well-connected hand out fertilizer, T-shirts, water tanks as a way to create dependence, which they try to sell as success. But they’re paternalistic projects; they create people who are dependent on the government and [who] work less.”

Father Ituarte agrees. “There are now social classes in the indigenous communities that reflect the social classes of capitalism,” he says. “There are now great indigenous capitalists, who have their own workers. Poverty is still what marks Chiapas, but it no longer encompasses all indigenous people. There are now rich and poor Indian; there are indigenous drug traffickers and indigenous politicians associated with organized crime. Many of them now live in the cities; they no longer work the land.”

"The communities nowadays are very divided because of politics. It's an economic attack of sorts."

Sensibility for the Poor

One thing has changed: By now Bishop Ruiz is a figure universally accepted as one the most important in Chiapas’s history, even by the elites. By the closing years of his tenure, political candidates would visit him to boost their images. Few now question his influence or accuse him of being a leftist instigator, as many did in the past.

But according to Pedro Arriaga, there are still signs that Mexico’s political elite are not entirely comfortable with the legacy of Bishop Ruiz. When Pope Francis visited his tomb last year, Father Arriaga was in charge of media relations. He recalls how Televisa, Mexico’s largest broadcaster and generally considered to be pro-government, refused to place cameras showing the pope praying at the bishop’s tomb. It refused to broadcast images of a choir composed of survivors of the Acteal massacre.

“That’s how the media in Mexico still work. They wouldn’t give the survivors of Acteal a chance to denounce the violence. They wouldn’t show Don Samuel as part of the visit,” he says.

But such subtle obliterations did little to diminish the significance of Pope Francis’ visit to Chiapas last year, generally considered a show of support to the continuing influence of Bishop Ruiz on the church’s approach to Mexico’s indigenous communities.

“It was very clear to me that the visit of Pope Francis, the fact that he came here to pray at the tomb, was a way of acknowledging the legacy of Don Samuel,” says Father Ituarte. “Like Don Samuel, the pope has an enormous sensibility for the poor, based on his experiences with the poor in Buenos Aires. He could not have come to Mexico without visiting Chiapas.”