Rodolfo Cardenal, S.J., serves as professor of theology and director of the Romero Center at José Simeón Cañas Central American University (UCA El Salvador) in El Salvador. An expert on Central American history and the relationship between church and state in the region, he knew Rutilio Grande, S.J. (1928-1977) before a death squad assassinated Father Grande on March 12, 1977. It was his assassination prior to the Salvadoran Civil War that galvanized San Salvador’s archbishop St. Óscar Romero to pursue his own path of advocacy for the poor, one that would lead to his martyrdom three years later in service of a faith that does justice.

An early pioneer of ecclesial base communities in Latin America, Father Grande worked in the countryside among campesinos. He organized the poor local farmers into lay-led evangelizing teams that advocated for their own rights. His work advocating for justice among the poor led right-wing government death squads to allege he was spreading Marxist teachings, and he was assassinated as an enemy of the government.

After Pope Francis approved the beatification of Father Grande as a martyr for the Catholic faith, Father Cardenal published his definitive English-language biography of the man, translated by Joseph V. Owens, S.J.: The Life, Passion, and Death of the Jesuit Rutilio Grande(Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2020). With an afterword by Jesuit liberation theologian Jon Sobrino, this publication follows more than 40 years of research. Father Cardenal started it shortly after Grande’s death.

On Nov. 6, 2020, I interviewed Father Cardenal by Skype about Father Grande. The following transcript of our conversation has been edited for style and length.

What were the circumstances surrounding Rutilio Grande’s killing? What was it about his work with the base ecclesial communities of rural El Salvador that provoked a right-wing death squad to machine-gun Father Grande to death along with an old man and a boy from his rural parish?

It was a very difficult time. The popular sentiment of the masses was asking for rights and organization, for land reform and for a more equal society. The hierarchy of landowners decided to act in alliance with the military to not give up anything because of the fear that if they gave up a little, the poor would take it all. Rutilio’s parish at Aguilares was a very important center of this work for justice; they knew he was a leader and they decided to kill him.

Rutilio Grande was a witness of faith and defender of justice for the peasant.

What was the state of Salvadoran church-state relations in 1977, when a right-wing death squad killed Father Grande?

The church in El Salvador at that time was very conservative, against the teachings of the Second Vatican Council and [the teachings of the Latin American bishops promulgated in the Medellín Document in 1968], being very close to the military and the oligarchy.

What do we know about the old man and the boy killed along with Father Grande?

We do not know much because the survivors from that period don’t say much. They don’t want to talk so much about what happened. What we know we know from the testimony collected at that time: The old man was close to Rutilio, both were together around the parish, and the boy was a normal peasant boy who was just catching a ride to El Paisnal. Both were very poor, like most of the people of El Salvador and Aguilares at that time.

Saint Óscar Romero, the archbishop of San Salvador who preached at the public funeral of Father Grande and was himself martyred while celebrating Mass three years later, had been close friends with him. How did Grande’s death affect Romero?

When Rutilio Grande died, Romero became more radical. It’s common to talk about the “conversion” of Monsignor Romero, but that’s not completely true. When Rutilio died, Romero began speaking out more clearly and radically, and you can see that in his homilies from 1977. His clarity, his prophecy, his forcefulness—it’s a different Romero. I say in the book that the great miracle of Rutilio is Monsignor Romero.

When Grande died, Óscar Romero became more radical.

You knew Father Grande before his assassination. How would you describe him personally?

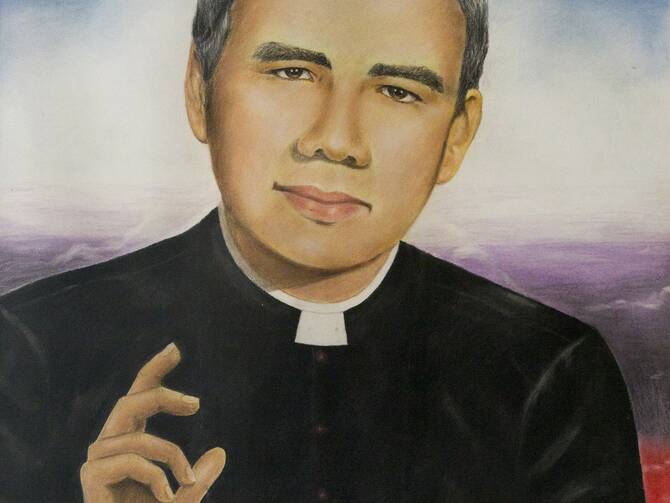

He was a typical Salvadoran man—not black skin, not light skin, but very dark like any moreno. He had white hair, was serious, always wore a black or white clerical shirt. But he always wanted to be around people and talk to people—a nice guy, a serious guy, but you had to work to get to know the real Rutilio. The people found him a very compassionate man, very close to them; he understood them and was very special.

What inspired you to begin writing a biography of Padre Grande so soon after his death, a project that has taken you the better part of your life to complete?

When I finished my postgraduate studies at the University of Texas in Austin in the second part of 1977, the Father Provincial at the time asked me to write a biography for the first anniversary of his death in March 1978. I started working and found that the volume of material in the archive was huge. After writing a short biography, I decided with the permission of the provincial to write a more extensive biography, which took me from 1978 to 1998. When the process of canonization started, I had to rewrite the biography, and the English volume we have now is very new.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Always from the beginning, my desire has been for the Salvadoran people to know the life of Rutilio and the life of the Salvadoran church. I think I did that. The first biography was very widely read in 10,000 copies. The second biography had something like 2,000 or 3,000 copies. This new book has been very well received and will be in more demand when he is beatified and canonized. I think Rutilio is very important for the understanding of the Salvadoran church and of Romero; you cannot understand Romero without understanding Rutilio. Now this translation into English, a surprise that I am happy about, is for people beyond El Salvador.

Father Grande is more than just a Jesuit saint, but a saint for the clergy and people of El Salvador.

Prior to Grande’s death, the Society of Jesus had committed itself to promoting “a faith that does justice.” In what ways did Father Grande live that out?

If we take the service of faith and promotion of justice from the Jesuit General Congregation 32 seriously, then Rutilio represents that ideal, something that Father General Arrupe said at the time. He is a symbol of the Central American Jesuit Province and the church of El Salvador, a church of martyrs.

In addition to writing his biography, how did you get involved with preparing the documentation for Grande’s beatification cause?

Because I was the Jesuit most familiar with Rutilio through my writings, I was the one who knew him best. The process was taken up not by the Society, but by the archbishop of San Salvador, although the Society’s postulator [who presents a case for the canonization or beatification of an individual to the Vatican] did the initial work on his canonization cause in Rome. So he is more than just a Jesuit saint, but a saint for the clergy and people of El Salvador.

With Pope Francis approving the beatification of Father Grande, there is only one more step before he can be canonized as a saint. To help his cause, would it be appropriate for Catholics to pray to Father Grande as a patron saint and martyr of the poor?

I would like that, yes. I think the bishops are just waiting for Covid-19 to clear up before having a big celebration for the beatification.

If you could say one thing to Pope Francis about Rutilio Grande, what would it be?

You know, when the pope was the provincial of Argentina, he read the fifth version of my biography. We know he read it, because he sent two letters to the Central American Province. The first letter said he had received the book; the second letter said he was reading it and Rutilio was a saint and martyr. So what I have to tell the pope, I have already said in my book.

If you could summarize the life of Jesuit Father Rutilio Grande in one sentence, what would it say?

Rutilio Grande was a witness of faith and defender of justice for the peasant.

More from America:

- I knew the Jesuits killed in El Salvador. Today, we can begin to heal.

- Ita, Maura, Dorothy, Jean: The legacy of 4 missionaries murdered in El Salvador 40 years ago

- Forty years after Óscar Romero’s martyrdom, El Salvador sees a harvest of martyrs

- Pope Francis signs off on Vatican budget with a multimillion-dollar deficit

- It’s official: St. Patrick’s Day is canceled in Ireland