In case you haven’t been paying attention, Andy Warhol is back. Honestly, though, he never really left.

Like Melville’s mythic white whale, the iconic white-wigged artist and prophet of modernity slips away from public view for brief periods of time only to breach the waters of our collective consciousness again in powerful and surprising ways. Warhol’s art seems to grow in value with each passing year. His “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn” screen print recently sold for a record $195 million, making it the highest price paid for a piece by an American artist at auction.

This news comes as Warhol’s work is powerfully visible in “Revelation,” an exhibition recently on view at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York, which explored the influence of Warhol’s religious imagination on his art. In addition, Warhol’s fascinating life is the subject of a recent London play (“The Collaboration”), an Off Broadway musical (“The Trial of Andy Warhol”) and an immersive walking tour of New York City called “Chasing Andy Warhol.” He is also the focus of a documentary streaming on Netflix since early March, “The Andy Warhol Diaries.”

Yet for all of this exposure, Andy Warhol remains an enigma.

The fact that Warhol is made so visible to us by means of multiple media—stage, screen and in a traditional museum setting—mimics Warhol’s own obsessive dabbling in as many forms of artistic media as were available to him in his lifetime. The man who was credited with the prescient prediction (pre-YouTube and pre-TikTok) that everyone would eventually achieve 15 minutes of fame has clocked many more than that. Warhol has been dead for 35 years, but that hasn’t stopped him from making headlines.

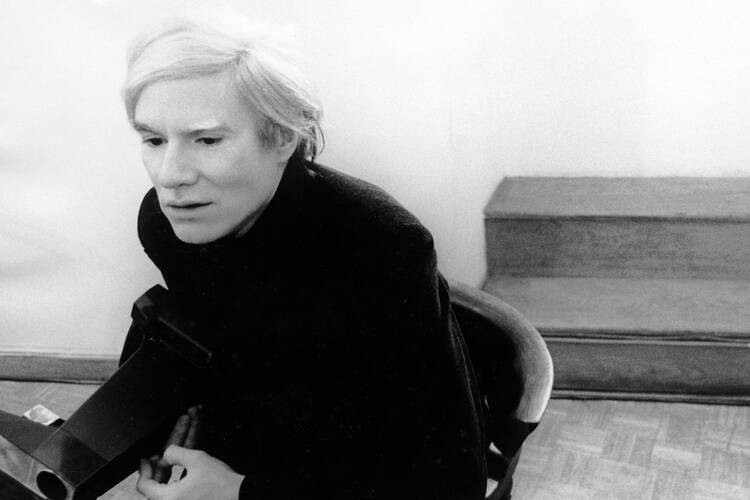

Yet for all of this exposure, Warhol, again like Melville’s whale, remains an enigma. He is a serious artist, he is a crass commercialist; a sensitive soul, a shameless huckster; a wild party boy, a Catholic kid from Pittsburgh; a painful introvert, a celebrity hound ravenous for fame. The more we see of him, the less we understand him. This, of course, was Warhol’s intention. To combat the easy categorization the world might try to impose on him, he invented a persona that could not be reduced to any single set of descriptors.

‘The Andy Warhol Diaries’

The construction of this mythical self is at the center of the Netflix documentary. “Andy Warhol’s greatest work of art is Andy Warhol,” observes art dealer and friend Jeffrey Deitch, one of many celebrities, fellow artists, critics and confidants who appear in the series. Over six hourlong episodes, we also hear, through A.I. technology that uncannily replicates his voice, Warhol “reading” from his diaries and telling his own story. We hear him give voice to his fears (he has many), fall in and out of love, critique the artists and celebrities whose company he keeps, make boastful declarations of his ambitions and poignant admissions of his failures, and wrestle with existential dread. While it’s true that no one really knows Warhol, thanks to the diaries—first published in 1989 and now made available to millions on a media platform Warhol would have found enviable—we are given access to his personal life and private thoughts, which help to humanize him, remove the impassive mask (if only for brief intervals) and enable us to see the passion of Andy Warhol.

It is hard not to be moved by Warhol’s strange life: his beginnings as a shy gay Catholic boy in a steel mill city; his family’s identity as outsiders even among the other Slavs in immigrant Pittsburgh (the family was Carpatho-Rusyn rather than Czech, Slovak or Polish); his knowledge of himself as a person possessed by a passion for beauty in a singularly unbeautiful place; his escape to New York City in pursuit of his vocation as an artist; his unlikely commercial success catapulting him to unimaginable fame and wealth; his two longtime love affairs that he insisted on representing to the world as platonic friendships; and the assassination attempt that marked him for life, both physically and psychically, the consequences of which would lead to his death 19 years later. “The Diaries” reveals that each of these periods of Warhol’s life, even the ostensibly enjoyable ones, were permeated by suffering, and much of that suffering was rooted in the painful reality of being a gay man in a world that he knew despised him.

Warhol’s wounded body echoes and participates in Christ’s story, his passion giving him a taste of his Passion.

In the show, Bob Colacello, a longtime friend and editor of Warhol’s magazine, Interview, suggests that one of the chief reasons Warhol created such an air of myth and mystery around himself was to keep his true identity, particularly his sexuality, out of the public eye. He also acknowledges the importance of Warhol’s formation in the Byzantine Catholic Church. One of the few sources of beauty in grim, gritty Pittsburgh was St. John Chrysostom Church. Warhol’s mother, Julia Warhola, was an observant Catholic, taking her children to Saturday night vespers and three Masses on Sunday, where they were surrounded by Byzantine icons.

These powerful portraits of the saints would inform Warhol’s own practice of portraiture as an artist, argues Colacello: “All his really important works were icons—figures to be venerated.” And yet the same church that fueled Warhol’s imagination also condemned his homosexuality, an aspect of himself he was aware of at a young age. Inevitably, his relationship to his faith and to God was fraught, complex and full of tension—the kind of tension that manifests itself in art.

‘Revelation’

In a wonderful instance of serendipity, as I was watching “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” I was able to visit the “Revelation” exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. Assembled by the curators of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the exhibition featured over 100 items that attest to the powerful role played by Catholic tradition, ritual, language and symbolism in Warhol’s life and art. Ranging from Warhol’s baptismal certificate to photographs of the icons in Warhol’s childhood church; from his paintings of the Madonna to his series of silkscreen photographs featuring America’s grieving madonna, Jackie Kennedy; from his obsessive depictions of “Death and Disaster” to his monumental studies of Leonardo’s “Last Supper”—the exhibition focused on the ubiquity of the idea of the Incarnation, on corporality and embodiment, and on the centrality of suffering in human life. In gallery after gallery, Warhol’s Catholic imagination was on full display, enabling the viewer to see a key element of his work that is just hinted at in “The Diaries.”

One of the most striking images I saw during that visit is Richard Avedon’s photograph of Andy Warhol’s torso taken a year after he was shot in 1968. A single bullet, fired by a mentally ill woman who accused Warhol of stealing a manuscript she had sent him, pierced his lungs, his liver, his esophagus, his stomach and his spleen. Warhol was thought to be dead by the doctors who tended to him at Columbus Hospital in New York until a private practice surgeon, Giuseppe Rossi, noticed the contraction of one of his pupils in the harsh hospital lights and was able to perform the emergency surgery that saved Warhol’s life. (This scenario is powerfully narrated by Blake Gopnik in the introduction to his exhaustive biography, Warhol, from 2020—another recent laudable attempt to penetrate Warhol’s mystery.) Lazarus-like, Warhol was resurrected to a new life.

Warhol’s suffering takes many forms in “The Andy Warhol Diaries” and is particularly evident in his relationships.

But that new life would be characterized by fear and pain. Warhol would have to wear a corset to keep his organs in place for the rest of his life. His diet and digestion would be affected, and he would have gallbladder trouble. It was surgery for the latter ailment that would kill him eventually. Warhol would die of complications in the hospital, a place that filled him with dread after the trauma of the shooting, in 1987.

Avedon’s photograph is striking in part because it is both prophetic and charged with all of this history. It is also striking because it is the portrait of a crucifixion. Seen in that gallery—set beside Warhol’s depictions of Christ on the night before his passion; set beside his famous icon of a handgun, the instrument of Warhol’s torture and death; set beside his massive portrait of a skull, evoking Golgotha (“The Place of the Skull” and site of the crucifixion)—Warhol’s wounded body echoes and participates in Christ’s story, his passion giving him a taste of his Passion.

Warhol’s suffering takes many forms in “The Diaries” and is particularly evident in his relationships. His friendship with the brilliant young artist Jean-Michel Basquiat begins in joy and is fueled by exuberance as the elder mentor and younger protégé collaborate to create some of the finest works of the late 20th century. (Before the sale of Warhol’s $195 million Marilyn icon, the highest priced work of American art sold at auction was Basquiat’s skull painting, which sold for $110 million.) However, the relationship eventually sours as the two are set against one another by the press and the art world, and they become competitors rather than collaborators. Warhol is left bereft. He would also lose many friends, as well as his partner, Jon Gould, to illness. The plague of AIDS was ravaging the gay community in New York City and elsewhere in the 1980s, filling Warhol with terror and grief.

‘The Last Supper’

Given this sense of impending mortality, it is perhaps not surprising that Warhol’s last artistic endeavor, regarded by Jeffrey Deitch as “a summation of Andy’s whole artistic enterprise,” would be “The Last Supper” series. Commissioned by Alexander Iolas, a Greek art dealer and friend who was dying of AIDS, the series comprises over 100 works, which Warhol worked on obsessively in 1985-86. Among these are Warhol’s famous large-scale paintings and silkscreens based on da Vinci’s iconic work. Warhol’s works feature Christ in the midst of his entourage of flawed male companions as the face of empathy and forgiveness. As Christ consecrates the bread, which is his body, he consecrates all flesh, saintly and sinful. His face exudes peace, compassion and kindness.

It is perhaps not surprising that Warhol’s last artistic endeavor would be “The Last Supper” series.

“The Diaries” follows Warhol to the opening of the exhibition in Milan, an event he attends despite the fact that he is quite ill, and narrates the painful journey back to New York, where he is admitted to the hospital in which he would die two days later, on Feb. 22, 1987. His via crucis finally concludes at his memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, an event attended by 3,000 people, many of them the glamorous celebrities Warhol sought out in life.

In his eulogy, the art historian John Richardson reveals details of Warhol’s seemingly secret Catholic life—that he attended Mass multiple times a week, “was responsible for at least one conversion,” and “took considerable pride in financing [his] nephew’s studies for the priesthood.” He waxes eloquent, stating that Andy “fooled the world into believing that his only obsessions were money, fame and glamor and that he was cool to the point of callousness.” In reality, “the callous observer was in fact a recording angel. And Andy’s detachment—the distance he established between the world and himself—was above all a matter of innocence and of art.”

And so we are brought back to the theme with which we began: Warhol’s artful dodging of intimacy and authenticity. Warhol’s diaries are a strange genre. Rather than a text written by the author, they are transcriptions of daily phone conversations Warhol had over the course of 10 years with the freelance writer Pat Hackett, who edited and published the diaries two years after Warhol’s death. “The diaries were different because the diaries were Andy’s thoughts in Andy’s words,” Hackett states in the documentary. “No other part of his work shows this.”

Yet even as Hackett makes a claim for the unprecedented authenticity of the diaries, she undercuts it with an equally telling statement: “Andy could have just tape-recorded himself, but Andy wanted an audience.”

We can’t help but wonder about the diaries, just as we wonder about every Warhol performance, whether this exercise was but another performative gesture in a life that was full of such gestures; or whether this time, on a regular basis, for a few minutes each day over a decade, Andy was being genuine. There is, of course, no way of knowing. “I don’t think you will ever figure Warhol out,” says curator Donna De Salvo, “And I hope no one ever does.” The white whale is still out there, and so is Warhol.