A little after 9 a.m. on Oct. 1, 2012, my first day as editor in chief of America, I entered my new office at our old headquarters on 56th Street in Manhattan. I was greeted by a display of 13 photographs of my predecessors—“a rogues gallery” as Father Joe O’Hare, whose face is among the group, once called it. These were the men who, with varying degrees of skill and success, had shepherded this review through its first century. I felt then, as I do now, the grace and the burden of that legacy. More the grace, I suppose, especially now, as I prepare to lay down the burden. My photograph will join the others before the year is over, and I will become a part of America’s history. That deadline has me taking stock of the last decade I have spent working alongside my colleagues, and the history we have made together.

The task before us on that first day was simple to conceive and difficult to execute: to ready America for a new century of work. Our goal was to transform the organization into a multiplatform media ministry, one that would produce content in addition to our flagship print magazine, including on the web, on social media, and through audio, video and live events. A decade later, the fruits of our labors are apparent. We have redesigned and relaunched America’s print and digital editions, launched a video division, started a media fellowship for young professionals, instituted a travel and pilgrimage program for our readers, rebooted the Catholic Book Club, produced several groundbreaking podcasts, and recruited a worldwide network of correspondents and contributing writers.

In 2012, America employed 16 people. Today, we employ 43 women and men, and the vast majority are lay people. Our website has about two million unique visitors a month, more than 10 times what it was in 2012. Even the number of print subscribers is twice what it was that first day. America is practically unrecognizable from the magazine I went to work for as a Jesuit novice almost 20 years ago.

I am immensely proud of the team of dedicated professionals who accomplished this transformation. I have often said that the best part of my job is going to work every day with the smartest, hardest-working, most dedicated group of people I know. And I am immeasurably grateful to you—our readers, listeners, viewers, commenters, in short, our community—who have made it all possible. America does not exist for its own sake, but in order to serve you. If they were here today, each of the 13 men in that “rogues gallery” would remind me that the relationship between America and its readers is a sacred trust. That is why, soon after my first day in 2012, I wrote to you, in the form of an essay in these pages, “Pursuing the Truth in Love,” in which I outlined America’s editorial direction for a new century of work. As I wrote then, “America is not a magazine, though we publish one; nor is America a Web site, though we have one of those as well. America is a Catholic ministry, and both of those words—Catholic and ministry—are carefully chosen.”

What does it mean to be a Catholic media ministry in the contemporary United States? By far the hardest part of our work was answering that question—even more difficult than overcoming the significant operational and commercial challenges we faced. That is because our answer to that critical question sailed our relatively tiny ship directly into the political and ecclesial winds.

Confronting Polarization

“Every Christian ministry, as a participation in the one ministry of Christ, is a ministry of reconciliation,” I wrote in “Pursuing the Truth in Love.” If that is so, we reasoned, then the urgent task for our communications ministry would be to bring people together, to put folks in conversation who were not accustomed to talking to each other. We wanted America to address directly the ideological partisanship and polarization that undermines American democracy and enfeebles the church’s witness.

It was a tall order, even then.

You may recall that I announced in that same issue in 2013 that America would stop using the words liberal, conservative and moderate when referring to our fellow Catholics in an ecclesial context. Those words are useful in secular politics, but not necessarily in the church, which is an altogether different reality—political, for sure, like all things human—but also radically apart, for our unity as a church resides not in some shared political credo but in the body of the risen Lord.

The solution to the problem of ideological warfare cannot be more ideological warfare.

Many people told us that avoiding those political terms would prove difficult, but that seemed to say more about the depth of their attachment to construing the church in factional terms than to the actual challenge at hand. It was relatively easy to adopt the style rule; we are writers—we simply used different words. The hard part was convincing people why the change was necessary, why the ideological partisanship embedded in the ecclesial use of such terms was and remains so dangerous.

“An ideology,” wrote the political theorist Kenneth Minogue, “is a set of ideas whose primary coherence results not from their truth and consistency, as in science and philosophy, but from some external cause; most immediately, this external cause will be some mood, vision, or emotion. The intellectual mark of ideology is the presence of dogma, beliefs which have been dug deep into the ground and are surrounded by semantic barbed wire.” Whether they originate with the political left or right, or are draped in secular or religious sentiment, ideologies are a form of circular reasoning, which shut down the conversation among all but their adherents.

I am sure you know exactly what I am talking about, for you see the effects of ideological partisanship every day, on cable news, in the newspaper and on your social media feeds. Indeed, it is everywhere—from the Academy Awards ceremony, to our elementary schools, to our dining rooms. Pope Francis has spoken about it repeatedly: “The concept of popular and national unity influenced by various ideologies is creating new forms of selfishness under the guise of defending national identity,” he has said.

Ideologies are particularly dangerous for Christians, for they turn the church in on itself. The pope has warned us of how “the faith passes, so to speak, through a distiller and becomes ideology. And ideology does not beckon [people]. In ideologies there is not Jesus: in his tenderness, his love, his meekness. And ideologies are rigid, always. And when a Christian becomes a disciple of an ideology, he has lost the faith: he is no longer a disciple of Jesus, he is a disciple of this attitude of thought.”

And so for the last decade we have tried to help counter the effects of ideological partisanship by breaking down the echo chambers it relies on; to host a different kind of discourse, a forum for a diversity of viewpoints. What have we learned? Quite a lot. And some of those lessons are worth recalling, because, for starters, America is going to continue this approach. And one of the biggest lessons is that this approach is worth continuing.

We still believe in the indispensable value of competing ideas, which should form the substance of our discernment.

My successor will surely bring change and innovation—all 14 of his predecessors have done that—but I also know that the entire organization, from the board of directors on down, remains committed to leading a conversation among diverse voices. We need this witness now more than ever, for its own merits, certainly, but also because we need to show that a media group can take such an approach and can also be commercially successful.

The Church and the World

My successor, of course, will face some vigorous headwinds of his own, for the problem of ideological partisanship is even worse than it was in 2012—exponentially worse. There are many statistics and scholarly reports that demonstrate this, but there is perhaps no clearer evidence than the attacks on the U.S. Capitol by U.S. citizens on Jan. 6, 2021. It is an event that in 2012 seemed inconceivable. Rarely in the long century since America magazine was founded have the norms and institutions that safeguard our national life been under greater strain.

The Catholic Church in the United States mirrors these sharp divisions along partisan lines. A recent Pew Research Center report demonstrated that “Catholic partisans often express opinions that are much more in line with the positions of their political parties than with the teachings of their church.” The Catholic vote, once courted, no longer exists as a uniform bloc—if it ever did. One hardly has to look beyond Twitter to see evidence of this. We have entered an era in which Catholics cannot even agree on the answer to the old rhetorical question: Is the pope Catholic?

Over the last decade I have heard from some people that they think the crises in our democracy and in our church are so menacing that America magazine should abandon its commitment to hosting a diversity of voices and should instead take sides in the partisan warfare; that, in 2022, our editorial commitment to balance and diversity of opinion seems quaint if not a little dangerous. But that suggestion stems from the same Manichaean worldview that actually powers polarization—the conviction, on both sides of the partisan divide, that we are engaged in some unprecedented, apocalyptic struggle between good and evil. Yet that is precisely the kind of “simplistic reductionism” that Pope Francis has warned us against.

In his address to the U.S. Congress in 2015, Pope Francis cautioned against seeing the world only in terms of “good or evil; or, if you will, the righteous and sinners. The contemporary world, with its open wounds which affect so many of our brothers and sisters,” he said, “demands that we confront every form of polarization which would divide it into these two camps. We know that in the attempt to be freed of the enemy without, we can be tempted to feed the enemy within.”

We speak truth not just to those in power but to those who actually have real power over us.

Some will no doubt point out that a lot has changed since the pope said those words in 2015, that America’s editorial approach belongs to a classical liberal order that is crumbling around us. I agree that the threat is real, but I fail to see how we can save the liberal order by abandoning it. And saving it is our urgent task, for whether we like it or not, the effective operation of American-style democracy is inseparable from the principles of objectivity, accountability and pluralism that belong to the liberal order. The solution to the problem of ideological warfare cannot be more ideological warfare. Democracy only works in a marketplace of ideas where voters can shop for their choices. “A nation that is afraid to let its people judge truth and falsehood in an open market,” President John F. Kennedy said, “is a nation that is afraid of its people.”

Yet as the author Jonathan Rauch recently noted, the metaphor of the marketplace gets us only so far, because ideas do not talk to each other, people do; and in the contemporary United States “our conversations are mediated through institutions like journals and newspapers and other platforms; and they rely on a dense network of rules, like truthfulness and fact-checking.” Without such conventions, there is only the barroom brawl of social media.

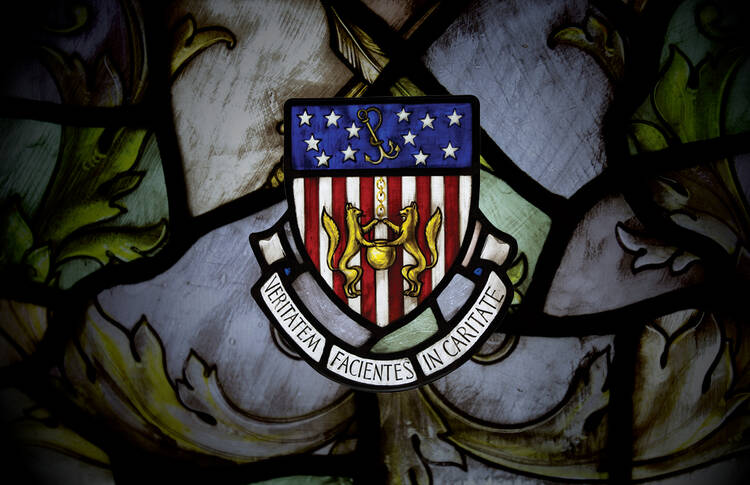

At the same time, America’s mediation is not disinterested. We make no claim to complete objectivity, as if we are Dian Fossey observing gorillas in the mist. America is a Catholic, Jesuit review, and we believe in balance and diversity, not in spite of our Catholic identity, but because of it. “True to its name and to its character as a Catholic review,” the editors wrote in our first editorial in 1909, “America [is] cosmopolitan, not only in contents but also in spirit.” (Read the first editorial in its entirety on Page 32.) Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J., the 10th editor in chief, put it this way: “A Catholic journal of opinion should be reasonably catholic in the opinions it is willing to consider. Which is not to say that catholic means indiscriminate. It does mean, however, that we will publish views contrary to our own, as long as we think they deserve the attention of thoughtful Catholics.”

We still believe in the indispensable value of competing ideas—besieged though this value is in the academy and elsewhere. An intelligent, contested and charitable public discourse should form the substance of our discernment in both the church and the world. It is ironic that at a time when the value of such diversity is being called more and more into question, we should have a pope who has put it into action in unprecedented ways. Pope Francis obviously believes in God, but he also engages in dialogues with atheists. He believes in a socially conscious approach to economics, but he has met and spoken with capitalists. He has spoken out strongly against what he calls “transgender ideology,” but he knows and has met with transgender people. The pope has demonstrated that engaging with opinions that are different from your own does not require you to abandon your own deeply held beliefs. While there is little that human beings do that surprises me, one thing I will never understand is why we so often feel existentially threatened by people who have different views.

One thing I will never understand is why we so often feel existentially threatened by people who have different views.

Scott Hahn, the biblical scholar from Franciscan University? A lot of people like his work. Some do not. Kerry Kennedy, the president of R.F.K. Human Rights? A lot of people like her work. Some do not. I doubt that those two Catholics would agree about very much, but they have at least one thing in common: They both appeared in America in the last decade because we thought you should hear from them. And we have applied that standard across our platforms. In the realm of economics, for example, we have published capitalists, communitarians, social democrats, libertarians, even a communist. No one who reads America’s unsigned editorials could mistake most of those opinions for those of our editorial board. But offering you our corporate opinion is but one, relatively small part of what America does. Our main task is to host opinions, to expose you to a variety of individuals and groups, all within the broad spectrum of Catholic opinion.

I wrote in 2013, “there is no faithful Catholic voice that is not welcome in the pages of America; there is no quarter of the church in which America is not at home.” As I have made the case for our approach over the years, I have sometimes been asked something like, “Well, would you publish Hitler?” For the record, no, we would not. I don’t think Herr Hitler qualifies as a faithful Catholic. But the problem is not really the relatively short list of people we would never publish, but the increasingly long list of people whom various ideologues and partisans think we should never publish. Polarization makes us think that subjects are closed when they are not, or shouldn’t be. Applying Catholic teaching in the real world is a difficult calculus, and few of the choices are obvious. What one person thinks is objectively false, someone else thinks is debatable, or we judge at any rate that a sizable part of the Catholic population judges it to be debatable and the authors’ views are worth reading. When you enter the conversation at America, you are entering into the middle of it, not the beginning and not the end. That is why it is important to keep reading.

The blacklisting of authors because of their political views or associations, part of the so-called cancel culture, is a direct consequence of polarization and the ideological partisanship that fuels it. It is un-American, but even more, it is un-Christian, for in the Catholic worldview, truth is ultimately a person, Jesus Christ, the way and the truth and the light. Truth, in other words, is someone we encounter, not something we possess. Does it not follow that a Christian faith requires an open mind as well as an open heart?

Speaking Truth to Power

We have a catchword at America that we use internally, a kind of one-word summation of our editorial credo: fearlessness. Leading the conversation is not easy at any time, let alone in a time of intense polarization. The daily slings and arrows on social media take their toll. On those occasions when we have said or done something that proved unpopular, “fearlessness” became the watchword of the day. But courage and fearlessness are sometimes misunderstood, especially in this line of work. Speaking truth to power, for example, is an important thing to do, but it is also a tough thing to do, and it requires a lot of courage. There are places in the world, in fact, where speaking truth to power can get you killed. Jesus did it and that is exactly what happened.

One of the subtler but still damaging effects of ideological partisanship is that it can blind us to where power actually lies.

One of the subtler but still damaging effects of ideological partisanship, however, is that it can blind us to where power actually lies. It is sometimes said, for example, that America has to be very careful to avoid offending bishops because, unlike other media outlets, America is sponsored by a religious order. According to this view, America sometimes does not tell the bishops what they need to hear. But there are several problems with this thinking. First, it’s not true—we do offer respectful criticism when we think it is warranted. Second, every publication has things it would not say even if it wanted to. National Catholic Reporter would no more editorialize in favor of the church’s ban on female priests than First Things would editorialize in favor of same-sex marriage. Their readers wouldn’t tolerate it. You should not assume, moreover, that the editors of America all think the same way, or spend their days wishing we could say things that we can’t. That has not been my experience, at any rate.

But prescinding from that baseline, the charge that America might pull its punches—a critique that usually proceeds from an ideological view about structures and power—misconstrues where the power really lies. For America to criticize the bishops would not require much courage. They are (unfairly, I think) the least popular Catholics in the country. On the contrary, it takes some courage to tell Catholics that the bishops might be right about something. It took courage to withdraw our endorsement of the Supreme Court nomination of fellow Catholic Brett Kavanaugh. It takes courage to buck the prevailing liberal ethos on matters of human sexuality or abortion or economics. It took courage to say that Donald Trump was right on the few occasions when he was.

That is the kind of courage you should expect America to muster—to say things that might actually cost us. We speak truth not just to those in power but to those who actually have real power over us. I have learned in this decade that the most powerful force in America’s corner of the popular discourse is not Donald Trump (who’s never heard of us), or the U.S. bishops (who mostly like or tolerate us), but the social media users who police the boundaries of ideological orthodoxy with cynical and ferocious tenacity. They can be found everywhere, in every corner of social media and across the ideological spectrum. We should pay more attention to you and less attention to them.

Hope Ahead

I am proud of what we have done during this decade at America. We could have done more—there is always more to do—but I believe we have done our level best to be a part of the solution and not the problem. That the problem of ideological partisanship and polarization has only gotten worse is an unsettling trend, to be sure; but I am not hopeless, and there is a very good reason for that: I have met you. Yes, some people believe that we have just been jousting at windmills for this decade, that our conviction that a better public discourse is possible is nothing more than an idealist’s fantasy. But those who think that do not know you as I have come to know you. I have now traveled the length and breadth of this country—you have welcomed me into your parishes and your homes and have shared with me your hopes and fears.

I trust you. I know you do not fear new ideas, that you are not afraid of different viewpoints; that you are suspicious of claims not thought through to their consequences; that you value intelligence and, above all, charity. I know all of that because I know you. You give me hope, not a giddy, cock-eyed optimism, but a simple hope, born of our common faith, the very thing I wrote about in my first-day column in 2012; words we have sought to live by for a decade: “We simply hope that our review—in print and online—will serve as one model of a truly Catholic as well as a truly American public discourse, one marked by faith, hope and charity. In other words, we seek nothing more than to bear public witness to the healer of all our afflictions, the balm in Gilead, the One whose spirit even now lives among us, among the people of these United States.”