Back in the early 2000s, I enrolled in a writing workshop in Madrid. In one of our first meetings, the teacher invited us to close our eyes and picture the place we knew best. This was easy. Corpus Christi Church in Rochester, N.Y., has always been my hub.

“Describe the space,” he said, “while incorporating each of your senses.”

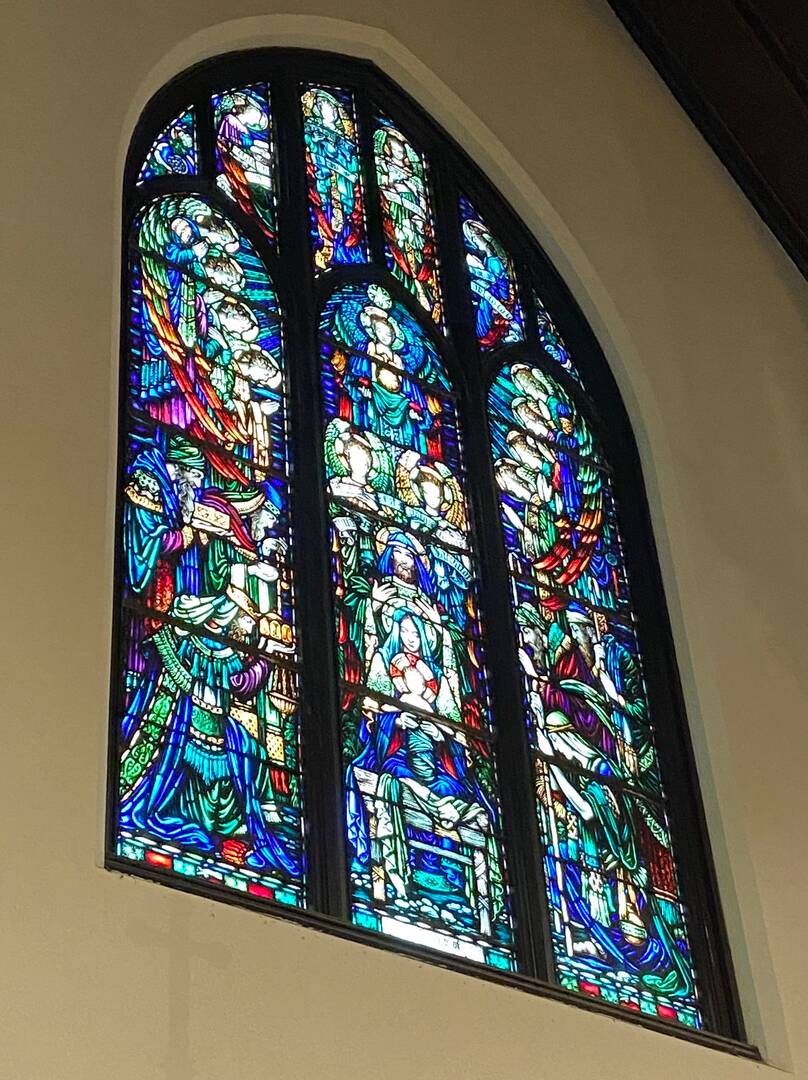

I wrote about the gothic arches and tangle of ivy covering the sandstone. I described the creak of pews and the scent of melting candles. I wrote about the statue of Mary with her garland of plastic roses and the wood-beamed ceiling where I once mistook a bat caught in the rafters for a dove. More than anything, I focused on the window over the high altar.

The window leaks light onto whitewashed walls, I wrote. And thickens the air with its hues. When the sun hits just right, the window spills its scarlet and sapphire into the church and everything’s on fire—if stained glass had a taste, it would be overripe plum, sweet and strong in the mouth.

The description is perhaps overdone. But it was Spain in July. Bougainvillea petals carpeted the walkways and the sangria freely flowed. The greater truth is that, overwrought or not, the description mirrored my affection, and I had admired that chancel window my whole life. As a child, I would sometimes arrive early to church just to stare into it as the sun rose and filled it with light.

My favorite church window is rather ordinary—but even the most ordinary examples of beauty offer a bridge to the divine. I have never looked into Corpus Christi’s window and not felt closer to God.

The description became a paragraph and then a passage in my first book. Then, a year or so after it was published, I received an email from Valerie O’Hara, whose book club had read the book. Of all the passages she had read, Valerie was most moved by my description of the stained glass. It turns out that Corpus Christi’s windows were produced by her family’s stained glass studio 100 years earlier. Valerie, too, was a glass artist who now ran the family business, and she was delighted to read how much her family’s work could matter.

More celebrated panels of stained glass than Corpus Christi’s chancel window certainly exist, and I have been lucky enough to see some of them for myself. I have wandered wide-eyed through cathedrals in Paris and Rome, bowed my head in Celtic abbeys, visited ancient Mediterranean sanctuaries and sat in an Eastern European church so resplendent I felt ensconced in a rare and glittering box.

Closer to home, western New York churches showcase creations by European masters as well as pearlescent panels of Tiffany glass. Just a few hours downstate, Union Church in Pocantico Hills features a series of stained glass panels by Chagall and a rose window by Matisse. Compared to Chartres Cathedral’s high-flung treasures and the feast of color that is a Chagall, my favorite church window is rather ordinary—but even the most ordinary examples of beauty offer a bridge to the divine. I have never looked into Corpus Christi’s window and not felt closer to God.

Designed to rise above the niches and scrollwork of the high altar, the window is a luminous wash of greens and blues joined by jewel tones and flame-tipped slants of scarlet and gold. A host of angels crowd the panel’s edges, while a concentration of blue suggests the Holy Mother’s robe, but the window’s subject otherwise takes a back seat to the interplay of color and light.

The transept windows clearly depict the Immaculate Conception and the Resurrection, but the chancel window, which is centered on the Nativity, is looser in form and nearly abstract. Close up, the figures are better defined, and the tableau more obviously illustrates the birth of Christ; shepherds lower their heads and the Magi bend forward with their gifts. But from the pews, the effect is deeply felt; and, more than anything, the window evokes upward movement and the beating of wings.

Valerie’s email about the window took me by surprise. I’d written about the color and shape and even the imagined taste of the glass, but until Valerie reached out, I never considered where the windows came from, who sketched the designs, painted the faces onto the saints, and painstakingly cut and fitted the glass. I tried to picture all the people who have looked into that window during weddings and funerals, baptisms and quinceañeras, and every single Sunday at Mass. I thought about my own particular window, of course, but of others as well. From medieval cathedrals to rustic chapels—most of us agree that stained glass is lovely and can elevate our experience at church. But how often do we consider the men and women who created these uplifting works of art? Looking into the history and origins of my favorite window helped me to appreciate it on another level.

Commissioned in the first decade of the 20th century, the window is one of 24 panels of stained glass planned for Rochester’s 14th Catholic church. Corpus Christi was incorporated in 1888 to accommodate the state’s booming western population and soon outgrew the small brick building in which it began. It took decades to raise the funds needed to break ground on a larger church; and when it was finally built and blessed by Bishop McQuaid in 1903, the envisioned windows were not yet in place. This was not unusual. Because stained glass is time-consuming and costly to create, patrons are usually required. Chartres had Louis IX and Blanche of Castile. Union Church downstate had the Rockefellers. Corpus Christi had the local carriage maker Joseph Cunningham.

Mr. Cunningham’s commission of the church’s most prominent window was one of the few planned windows to be installed. The nave was outfitted with amber-tinted “placeholder” glass to be replaced with original designs once other patrons emerged. But new patrons never emerged. The Depression struck, followed by war and suburban flight. Donations dried up, as did attendance. One hundred and twenty years later, the plain amber windows have become permanent fixtures. This is not as unfortunate as it sounds. The nature of stained glass renders even the humblest of panels grand. The placeholder windows transform summer’s glare and infuse upstate winters with warmth, making every hour a golden hour at church.

In closing her email, Valerie invited me to tour her family’s stained glass studio. More than a decade later, I finally took her up on the offer.

One of the first images you see when you walk into Pike Stained Glass Studios in Rochester is a photograph of a young Valerie O’Hara kneeling in an angelic white robe. The stained-glass rendering of Valerie’s heavenly likeness undoubtedly illuminates the window of a nearby church. Pike has always been a family business, which meant family and friends took turns posing for the photographs used as models for the full-sized drawings that would become patterns for the cutting and assembly of glass.

Valerie tells me the details of the studio’s history as she gives me a tour. After apprenticing with William Comfort Tiffany in New York, William Pike, the company’s founder, began his Rochester studio in 1908. As a teenager, Mr. Pike’s nephew James O’Hara spent summers working with him. After completing advanced degrees in New York, Mr. O’Hara and a fellow artist, Norma Lee, who was also his wife, moved upstate to work at the company, eventually assuming leadership.

Like her father, Valerie O’Hara came to the art young, working in the studio after school, beginning at age 12. By the time she graduated from the School for American Crafts at the Rochester Institute of Technology and began at Pike full-time, she had already been an apprentice for half her life. In 1987, Valerie bought the business from her parents and continues their tradition today.

Apart from the use of electricity-powered soldering irons and a steel wheel cutter, the process for creating stained glass windows has not changed much in 1,000 years.

The family’s windows adorn buildings throughout western and central New York. With more than 850 original designs by three generations of artists, their work is part of the region’s fabric. Most of their windows are found in churches, but people can encounter their colorful designs while cramming for exams in local libraries, attending soirees in area mansions or stealing a moment’s peace in the nondenominational chapel at Cornell University.

After viewing the gallery of images in the entryway, we pause at a table spread with sketches from the past century. I am struck by the magnitude and variety of the projects, their exquisite patterns, rich color and attention to detail. Styles range from Gothic and medieval to modern and Art Nouveau. Some projects require Valerie to blend the traditional with the contemporary, combining the unique story of a person or a place with classic imagery and design.

A commission for Rochester’s St. Stanislaus Parish, for instance, pairs the likeness of a 21st-century firefighter lost in the line of duty (19-year-old Tomasz Kaczowka) with the third-century St. Florian, who watches over the young man as he battles the flames. A window for St. James Episcopal Church in the Finger Lakes town of Hammondsport depicts scenes of local significance, like vineyards and Keuka Lake, and even a vintage Glenn Curtiss biplane piloted by the donor’s husband.

The award-winning artist leads me through a great bank of colored glass and shows me the space where each piece of glass is selected for color, then cut. We visit worktables where pieces are smoothed and painted before being assembled and slotted into lead strips, soldered at the joints and sealed. Each panel can take months to complete. The work is meticulous and time-consuming, but while designs are always adapting to changing aesthetics and purpose, the tools remain relatively simple. Apart from the use of electricity-powered soldering irons and a steel wheel cutter, the process for creating stained glass windows has not changed much in 1,000 years.

It is impossible to pinpoint the art form’s beginning. Stained glass windows are believed to have been inspired by the techniques of jewelry making, cloisonné and mosaics. Colored glass was produced and used for ornamentation throughout the ancient world. Some early Christians even arranged sheets of thinly sliced alabaster and travertine into wooden frames as a sort of precursor to stained glass in their churches. Archaeological evidence points to colored glass windows in seventh-century British monasteries, but the technique for fitting pieces of glass together with lead strips—as we know stained glass today—was not refined until the ninth century. Once it began, the medium flourished and peaked in the Middle Ages alongside the building of magnificent ecclesiastical sites. A glassworkers’ guild was formed in London as early as 1328. Known as The Worshipful Company of Glaziers and Painters of Glass, their motto was Lucem Tuam Da Nobis Deus, Latin for O God, Give Us Your Light.

“Stained glass is the only medium that relies on transmitted, instead of reflected, light.”

Then, as now, stained glass windows required mastery in both artistic and technical realms. Besides enhancing the space into which it is set, a window must weather the elements, bear its own weight and fit seamlessly into the architecture. As Valerie guides me through her downtown studio, she speaks as an artist, but also as a draftsman, glazier, cutter and engineer. In the early days, Pike employed different people in such specialty roles. These days, Valerie manages it all.

When the tour is over, I linger near an old window. Valerie has been more than generous, so I limit myself to one final question as I prepare to leave: “Why is stained glass so special?” I say. “How can a colored window so greatly affect a person’s experience at church?”

For the entire tour, Valerie has been knowledgeable but unassuming, as if she does not take for granted the ability of her work to uplift the human heart.

“Stained glass is the only medium,” she says, “that relies on transmitted, instead of reflected, light.”

I think of Corpus Christi’s chancel window. Fixed into its sandstone well for more than a century, it is nonetheless dynamic. Like the sky itself, color and form are linked to the movement of the sun and shift and deepen as the glass channels light. Even when a panel is clearly pictorial, stained glass relies on fragmentation and the transmutability of light and is, on some level, always moving and abstract. It’s an artful assemblage of colors and shapes, yes, but much more than the sum of its parts. In this way, a stained glass window functions more like a song or poem in its ability to move and move us as it transcends the material world.

One summer in the 1980s, a man came walking through my family’s city neighborhood. Ours was a dead-end street, compact and diverse. The houses were modest, but a handful contained panels of stained glass in the dining rooms. The leaded windows were small but fitted with a checkerboard pattern of tinted glass that obscured the view of porches and telephone poles while ornamenting the otherwise plain rooms.

No matter our religious affiliation, we hunger for pathways that exalt our spirits and transport us to something larger than ourselves.

We kids watched the man walk door to door. Most strangers were Jehovah’s Witnesses or men sent to collect the rent on household items our mothers leased, but this man did not discuss heaven or badger my mother for a payment on our color TV. Instead, he eyed the small window and offered her a few hundred dollars.

Most anyone lucky enough to have a panel sold it. The neighborhood was falling apart. People could hardly pay their electrical bill; what good was a bit of colored glass in the face of that? But my mother—who had sold my brother’s saxophone to buy Christmas gifts one year and bartered our dining room furniture as payment to the neighbor who had painted our house—said no. As much as she was willing to part with things and was always in need of money, my mother regularly chose beauty over practicality (often to our dismay). She sent the man packing. She might not have anything in her wallet but her bit of beauty was intact.

As with other elements of traditional worship, some view stained glass as fussy and old-fashioned. Given the serious financial, social and operational problems facing many church communities, focusing on aesthetically pleasing objects might seem frivolous and out of touch. At the same time, given that spiritually inclined Americans seem to favor a walk in the woods over Sunday Mass, it is important to remember the natural human inclination toward beauty and light. No matter our religious affiliation, we hunger for pathways that exalt our spirits and transport us to something larger than ourselves. The countless artists, patrons and congregations who sacrificed to build such awe-inspiring and luminous portals between the world as we know it and the world that lies beyond, did so to encourage and sustain our experience of the divine.

Like the bit of colored glass my mother refused to sell, Corpus Christi’s chancel window is my portion of beauty, worth more than its worldly value. It is my touchstone. It reminds me of the necessity of tending not only the body but the spirit, even and especially when times are tough. Our spirits are fed by many things—peals of unexpected laughter, bouts of wild generosity, the profound stillness of a winter night—but also by the light of the sun filtering through a panel of blue and green glass.