In 2006, Willie Nelson—author of some of America’s most beloved songs, noted marijuana enthusiast and rebel icon to musicians and music fans around the world—did something unexpected. He bought a church. Nelson, who was born in 1933 in the tiny town of Abbott, Tex., had learned that Abbott’s Methodist church, built in 1899, was in danger of closing because of dwindling attendance. At the celebration of the church’s rescue, Nelson told the assembled congregants and media that “[My] sister Bobbie and I have been going to this church since we were born,” and in honor of their musical childhood years, the siblings played a set of gospel songs.

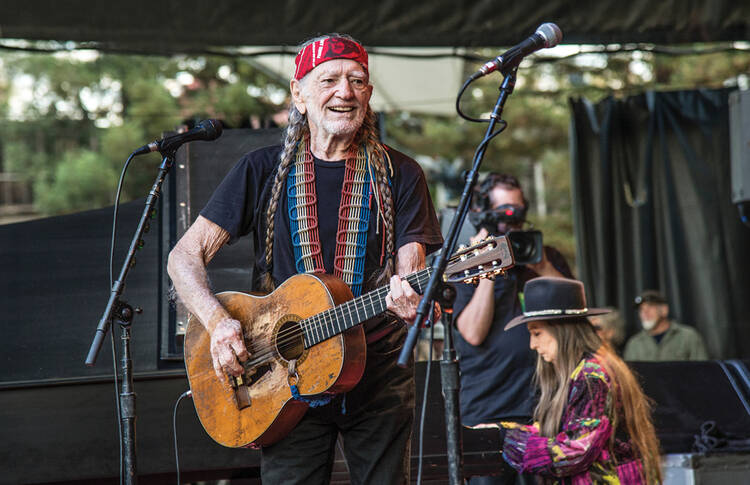

Willie Nelson might not be the first person who comes to mind when you think of a “Christian musician.” His trademark braids, beard and bandana, relics of his years as the co-founder of the Outlaw Country movement, aren’t a look you often see in church. His open defiance of the government on taxes and marijuana, and his idiosyncratic politics on everything from his support of L.G.B.T. priorities to the rights of American farmers, along with his four marriages, are also reasons why he does not fit neatly into country music’s often conformist environment. But Nelson, rebellious as he might be, has long talked about his admiration for the teachings of Jesus, and he continues to sing the gospel music of his childhood today. In fact, gospel music brought his family together during the Covid pandemic.

Willie Nelson might not be the first person who comes to mind when you think of a “Christian musician.” But he has long talked about his admiration for the teachings of Jesus.

Nelson’s live sets have featured gospel songs from the beginning of his career, and he has released at least half a dozen albums that primarily consist of gospel songs, from 1972’s classic “The Troublemaker” to 2021’s “The Willie Nelson Family,” recorded with his kids and sister while they sheltered in place during the Covid pandemic. It was during the pandemic that Nelson also lost his longtime drummer and best friend, Paul English, just as the virus was surging in 2020. Nelson’s big sister, Bobbie, who had played piano by his side since childhood and onstage with him since the early 1970s, also passed away, in early 2022 at the age of 91. Neither died from Covid, but you can imagine that a man who has spent most of his life playing music on the road with the same Family Band members for decades might be feeling the sharp sting of loss as he approached his 90th birthday this April. But every artist, every music fan and every religious person knows that music can heal. Music is a fruit of the spirit. And Willie Nelson has been offering musical healing for longer than many of his fans have been alive.

The Family

It’s hard to talk about Willie Nelson and religion without talking about Sister Bobbie, as he refers to her, and the tight bond between them that started with a hardscrabble, Depression-era childhood. When Bobbie passed away, Nelson wrote a note to her on his website titled “Dear Sister.” In part, it reads, “you were a natural musician from the beginning, and I would never have become the musician I am without you.” Nelson also reminisces about the day they played again in their childhood church, telling Bobbie that “when we play Amazing Grace together, I’m reminded that all songs are, in their own way, gospel songs.”

Methodism, like America, was founded by rebels. John and Charles Wesley broke off from the Church of England in the 1700s, and Methodism spread rapidly in Europe, but the Methodism that Nelson experienced in Texas likely had a very American bent. During the First and Second Great Awakenings of the 1800s, Methodist traveling revival meetings grew the denomination, and the Methodist emphasis on sanctification and the movement of the Holy Spirit would influence Nelson’s songwriting for the rest of his life. And Methodists have always been steeped in music. Charles Wesley himself wrote at least 6,000 hymns, including many Nelson and his sister likely grew up singing in church.

It’s hard to talk about Willie Nelson and religion without talking about his sister Bobbie and the tight bond between them.

In his 2015 book It’s a Long Story, Nelson wrote of his Christian faith that “I was a believer as a kid, just as I am a believer as a man,” and “I’ve never doubted the genius of Christ’s moral message or the truth of the miracles he performed.” When he is writing a song, Nelson says that he often wonders if it’s him or God pushing the pen. Sometimes, he reveals, he will ask himself: “Am I just a channel chosen by the Holy Spirit to express these feelings?” The first song Willie Nelson is reported to have learned to sing, at the age of 5, was “Amazing Grace.”

Nelson and Bobbie were bonded for life when their parents abandoned them as children, leaving them to be raised by their grandparents, who were themselves musicians and music teachers. Nelson got his first guitar at 6 and wrote his first song at 7. Bobbie was playing piano and a pump organ from the age of 5, and by the time they were both teenagers, they had moved beyond playing in church and began performing in Texas honky-tonks. Bobbie, who married as a teenager, lost custody of her three children in her first divorce because the court believed a woman who played honky-tonks couldn’t be a fit mother. She quit touring for decades and went to work for the Hammond Organ company so she could get her kids back. When Nelson called her up in 1972 and asked her to play gospel piano on the “Troublemaker” album, Bobbie said yes. They were rarely onstage without one another again until her death, Sister Bobbie’s long, flowing hair swaying with her as she sat at her brother’s side, making music together just as they did as children.

Any musician will tell you that when things are working musically, when a band is tight or a harmony springs forth naturally, that’s a spiritual experience.

When Willie Nelson started calling his band The Family in the 1970s, Bobbie might have been the only blood relative, but some of the other band members, like Paul English (drummer), Mickey Raphael (harmonica player) and Jody Payne (guitarist) would go on to play onstage and in the studio with Nelson for more than 50 years. These days, Nelson’s sons Micah and Lukas often join their father onstage, and Lukas’s band, Promise of the Real, has become a success of its own.

But it takes more than blood relations or playing together to make a family—and to keep it together. Any musician will tell you that when things are working musically, when a band is tight or a harmony springs forth naturally, that’s a spiritual experience. Throw in some gospel tunes and maybe you could call a Willie Nelson concert, hours long and full of singalongs and tributes to musicians from the past, a kind of religious experience too.

On the Road With Willie

When I was a child, my family had rituals: dinner each night at the table; Christmas Eve at the grandparents’ house, where you were allowed to open a single gift; church on Sunday night at the Newman Center.

But our biggest ritual was travel. My father’s sixth child was a 1971 VW Vanagon named Old Dog, plastered with National Parks stickers decades before “Van Life” was an idea in the mind of Instagrammers fed up with grind culture and the pressure to conform. All five of us kids would pile into the van with our parents in the front seat and a mess of sleeping bags in the back, ready to camp out for weeks on end, and my father would lean over and pull a tape from the glove compartment. Every trip started with Willie Nelson, and it was always the melody of “On the Road Again” that took us out of Oakland and onto the back roads. By the time I graduated from high school, I had rarely been on an airplane; but like a member of a traveling band, I knew the country I lived in from its roads.

Religiously, my family today is a very contemporary American tangle of lapsed and practicing Catholics, Buddhists, Jews and every flavor you can imagine of agnostic. We all revere nature and love hiking, backpacking and road trips, thanks to those ritualistic journeys in our childhood. But my late father, child of Irish Catholics, believed that God, the church, literature and music were all of a piece with those trips on the road. All of them were things you used to escape from the pressures and stress of work. My father was by nature a nonconformist who liked being alone but who also happened to be responsible for a very large family. I don’t remember seeing my father pray outside of church, but when he listened to Willie, Miles Davis, the Beatles, John Coltrane or Bob Dylan, I’m pretty sure that’s what he was doing.

A Willie Nelson concert is a ritual, always opening with “Whiskey River,” a Texas flag flying in the background.

A Willie Nelson concert is also a ritual, always opening with “Whiskey River,” a Texas flag flying in the background and Willie’s Martin guitar, Trigger, around his neck. It’s been played so much for so long that his guitar pick has bored a hole in the soundboard. You’ll hear songs you’ve heard a million times and you’ll sing along joyfully, and you’d better get comfortable because you’ll be there for three or four hours. Nobody knows how he keeps doing it, night after night after night. It’s a celebration, but it’s also moving to witness that level of dedication and persistence.

I married a musician, the son of a musician. My husband, a child of divorce, grew up both in Berkeley and in Austin, Tex., where his dad managed a western swing band called Asleep at the Wheel. My husband spent many nights as a kid at The Armadillo drinking Shirley Temples and taking in music. The Armadillo is a legendary Austin nightclub where The Family and many other bands honed their sound. Nelson fled the conformity of Nashville in the early 1970s for the more freewheeling Austin scene, where he let his hair go long and grew a beard and started collaborating with other nonconformist country musicians like Waylon Jennings, Emmylou Harris, Merle Haggard and Kris Kristofferson.

Every summer, Willie would host a huge, rowdy picnic at a ranch outside of Austin where bands would play and people would drink beer and eat barbecue. My husband still remembers burning his hand on a picnic grill on one of those Texas Fourth of July days. In our early days getting to know one another, my husband and I would listen to “The Red Headed Stranger” and “Phases and Stages” and “Shotgun Willie” over and over again. We still do.

My husband isn’t religious, but like many other musicians, for him the stage and the music studio are sacred spaces. Musical collaboration is communion, and playing live is a chance to share with an audience the fruits of struggling to keep a musical career alive over decades when it’s hardly a financially tenable career on its own. Writers like me mostly work alone, but musicians bond, and I often marvel at the depth of those connections. They are fathoms deep.

When I hear musicians talking about playing live and witness the intensity required to do it, I also think about my own experiences of spiritual direction, church and prayer. I think music is spiritual, and it’s clear that Willie Nelson does too.

In 2021, Willie was interviewed for the long-running television show “Austin City Limits” and was asked about his religious beliefs. He said, “Music will move you, period. It’ll make you laugh or cry or jump or clap your hands. And anything that will move you, do it.” But he added something that is, perhaps, the key to understanding what keeps him playing into his nineties, even after losing family members and friends. “Here’s what I believe,” he told the interviewer. “God is love, period. Love is God, period. You can’t have one without the other.”