This essay is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

The first time I saw Hana, she was standing at the back of a room, holding a dress in her hands. The dress resembled a quilt she could wrap around her body, and into that dress she had sewn a city. Inside that city she had sewn a world: with its own language, with fruit-bearing trees and with friends interlocking their arms and dancing. I had no way of knowing how immense that world had been or even that it was now both gone and saved. I had no idea that I would follow that dress as it would follow me.

That late October in 2016 seemed unusually cold, and I had not packed well. Even after more than a decade of living in the Middle East, I still forgot how frigid the autumn air becomes, especially in the barren areas along the desert. From my home in Jerusalem, I had traveled north and crossed the Sheikh Hussein Bridge into Jordan. Now, as my taxi headed south toward Amman, I watched out the window as green fields slowly gave way to the sprawl of the city. I studied the name scribbled in my notebook: Abouna Elian. On a subsequent page, I had written the name of a city, Qaraqosh, which comes from the word blackbird in Turkish. I was traveling in search of a city I had never seen. I was also trying to locate myself in a moment in history.

I was on the first leg of a journey that would eventually span nine countries—traveling to interview the women and men who had escaped war in Iraq and Syria, to learn what they had salvaged and brought with them. Women and men from Mosul and Al-Hasakah, Aleppo and Mount Sinjar: hidden historians carrying seeds, songs, recipes for rose petal jam, witnesses to communities uprooted and neighborhoods bombed. Muslims, Christians, Yazidis; women and men speaking Kurdish, Aramaic and dialects of Arabic unique to their cities.

‘No One Else Is Coming to Save Us’

My journey would begin by speaking with those who had escaped from Qaraqosh, a city in Iraq southeast of Mosul that had become synonymous with a tragedy. On Aug. 6, 2014, ISIS invaded Qaraqosh, and nearly the entire population, some 44,000 people, fled for their lives. Overnight, tens of thousands crossed the border to Iraqi Kurdistan to seek what they thought would be temporary shelter.

But ISIS remained in Qaraqosh. Months passed. Then a year. Much of Qaraqosh’s population began to scatter across the world, crossing borders and becoming refugees. Thousands traveled by plane to Amman, where they applied for visas at the embassies there in hopes of being resettled, largely in Australia. Almost all of them belonged to the Syriac Catholic Church; this was also the church to which I belonged in Jerusalem, where I lived with my husband and three children.

The sudden emptying out of Qaraqosh had shaken all of us. And so it had been the bishop of my own community in Jerusalem who had scrawled a name into my notebook after he flipped through his address book—Abouna Elian—referring to the priest in Amman responsible for pastoring the refugees of Qaraqosh. He asked that when I met Father Elian, I would send his greetings.

I arrived in Father Elian’s office in Amman that October morning. I found him sitting behind a desk littered with papers. He offered me espresso, which he had learned to make as a seminarian in Milan, and as we sipped, we took a moment to accustom ourselves to our different dialects of Arabic.

“Are you from here?” I asked.

“No, I’m from Qaraqosh in Iraq,” he answered. “I was born there, lived there for 27 years, became a priest, and then left to complete my studies in Italy. When I returned, I went to work in the seminary. And I was working there still when ISIS came.”

He began speaking in a rush, describing the events of Aug. 6, 2014, the feast of the Transfiguration, when ISIS invaded the city. I struggled to follow, for he was speaking of how he escaped a place that I was just beginning to understand had ever existed.

“Qaraqosh was around 50,000 people,” he continued. “Everyone left that first day, except for 30 or 40 of us who stayed. By the next morning, at around 2 o’clock, we looked around and said, ‘Forget it. ISIS is coming and no one else is coming to save us.’ At 4 o’clock in the morning we left.”

“It wasn’t just Qaraqosh that emptied out that day,” he continued. “It was the towns of Bartella and Bashiqa and Karamles, the entire area of the Nineveh Plains around Mosul. We fled to Ankawa, a neighborhood in Erbil in Kurdistan, but others from our city escaped to Sulaymaniyah and Dohuk.

’We left everything in a single night…everything.’

“In Ankawa, we stayed together, sleeping in the streets, in buildings and in churches, waiting. Then, last year I was sent to Amman to work with the refugees who were arriving here.”

“Would you mind telling me a little bit about what Qaraqosh was like?” I asked. Father Elian nodded.

“The most important thing to know about us is that we were the largest Christian town in all of Iraq, and one of the most ancient Christian towns in the world,” he said. “The language of our liturgy, of our traditions, and even our spoken language was Syriac, a dialect of the Aramaic language.”

Father Elian pointed to a stack of papers on his desk. These were the files for all the refugees in his charge—men, women and children who had escaped the cities of Qaraqosh, Bartella, Bashiqa, Mosul and Baghdad in Iraq—along with cities like Aleppo, Homs and Damascus in Syria.

“Look at how many of us we are.” He held up the pile of papers to show its weight. “We have 1,250 Syriac Catholic families here. Each one of those sheets of papers isn’t for one person—it’s for a family of four or five people. And the minute one family is resettled, another one arrives and takes its place.”

We sat for a few moments in silence. I stood up to leave, and he shook my hand. “Come to the Mass on Saturday at 5, at the Deir Latin Church in Hashmi al-Shamali,” he finished. “If you want to meet the people of Qaraqosh, you will find them there.”

‘This Is the Time to Begin Anew’

Four days later, I took a taxi to the Deir Latin Church in Hashmi al-Shamali in East Amman. I found a seat near the front of the church, watching as the pews filled up and the faithful extended into the back lobby. Nearly everyone was speaking a dialect of neo-Aramaic, a Semitic language that had centuries ago been the common spoken language of much of what is today the Middle East; it has now all but disappeared.

Father Elian approached the altar, followed by an assembly of deacons and altar boys and girls. All of them had become refugees. He began the liturgy in Arabic in deference to the country and the borrowed church in which they now found themselves, as well as to the scattered refugees from Mosul, Baghdad and Damascus among them who could not speak Aramaic.

“Today we begin a new liturgical year,” Father Elian announced solemnly during the homily. “We ask ourselves: ‘Who is Jesus to me?’ In the Gospel, all the disciples give the wrong answer. Only Simon Peter says: ‘You are the Messiah, the son of the living God!’” He paused. “We must also ask God to make our relationship closer. This is the time to begin anew.”

The choir began to sing, and I listened as their voices filled the room with a song—not in Arabic, but in Syriac this time, their community’s own language.

The choir began to sing, and I listened as their voices filled the room with a song.

I cannot quite describe what happened next. It was as if the space slowly began to be lit from the inside. One person after another began to sing along, first softly and then with more confidence, until the church was alive with the song of a people who—for a very brief moment—were home again.

The City Whose Song Had Been Saved

When the Mass was finished, I recognized the soloist from the choir walking in my direction. I introduced myself, and she shook my hand. “My name is Meena,” she said. “I’m from Qaraqosh.” I asked her how long she had been living in Amman. “For just a few months now,” she answered. She pulled a phone from her pocket and scrolled to a photograph of a house. The roof and the second story had been charred black, like someone had set fire to it and then blown it out. “That’s my home in Iraq,” she said quietly.

By now, the rest of the choir had joined us and Meena introduced them: her sister Mirna, Alaa’, Louis, and Wassim and Sonia, who were married. They were all refugees from Qaraqosh, and they spoke Arabic and English in addition to Aramaic, having been students at the university in Mosul.

“We left everything in a single night: our studies, our homes, everything,” Wassim said. “I was an engineer. We waited to see if we could return, but ISIS destroyed everything.”

His young wife, Sonia, who was pregnant, stood cradling her stomach with her hands. “We had been planning to get married in Qaraqosh,” she added. “I lost all that I had, even my wedding gown.”

“Were you all in the choir together in Qaraqosh then?” I asked.

Meena shook her head. “There were seven different Catholic churches in our city, and we were all members of different choirs. But when we arrived here, we found one another. We thought that we had lost everything. But then we understood that we could at least still save a church choir.”

“Would you mind singing something for me?” I asked. They nodded, and we returned to the sanctuary, where they took their places in front of the altar. Meena stood at the center, and they pulled out their cellphones from bags and back pockets. With their liturgical books destroyed, these phones had become their hymnals.

For a moment all of us were transported to that city.

They sang. Meena’s voice rang out clearly, leading them. I listened to them singing a language that could be on the edge of vanishing but was still alive in them, a song they had carried out of war and across borders. For a moment all of us were transported to that city whose song had been saved at the end of the world.

They finished. A silence held in the air. We walked out into the night streets together.

They shielded me from the onslaught of cars. Alaa’, one of the choir members who had been quiet until now, turned to me. “If you’re not too busy,” he said shyly, “we’d like for you to meet our families.”

The Dress

I followed the choir through the streets until we turned off into an alley and entered an apartment block. Alaa’ opened a door on the ground floor, and we all passed through. Inside, a dozen people had crowded around a television set to watch the news.

I took a seat and Meena sat beside me, translating from Aramaic so that I could understand.

“Is there something you’d like to ask people about?” Meena questioned gently. I had walked into what felt like sacred space, and I was hesitant to do anything but observe. I told her that if anyone felt comfortable sharing, I’d be grateful to hear a story that might help me to visualize Qaraqosh: something about their trees, their vegetables, their harvests, the names of their churches. Or if anyone had brought anything with them, like an icon, or perhaps even a dress.

“A dress?” Meena asked. I nodded.

“A dress?” she repeated, as though she might have misunderstood me, and I nodded again.

“You need to speak to my mother,” she said firmly. “She didn’t bring anything from Qaraqosh with her when we escaped. But she saved something of Qaraqosh with what she made.”

She saved something of Qaraqosh with what she made.

Meena called her mother from across the room. “Mama, show her your shal!” I turned to where her voice had been directed and glimpsed Hana for the first time, standing in the back of the room. She was perhaps in her 40s, with her brown hair pulled back in a ponytail, wearing a gray T-shirt and what appeared to be polka-dot pajama bottoms. When she heard her daughter’s request, she blushed. Others in the room encouraged her, until Hana disappeared and then reappeared, holding a plastic bag. She reached inside and pulled out a folded-up square of red and black checked fabric, which at first did not look like a dress at all but perhaps a tablecloth.

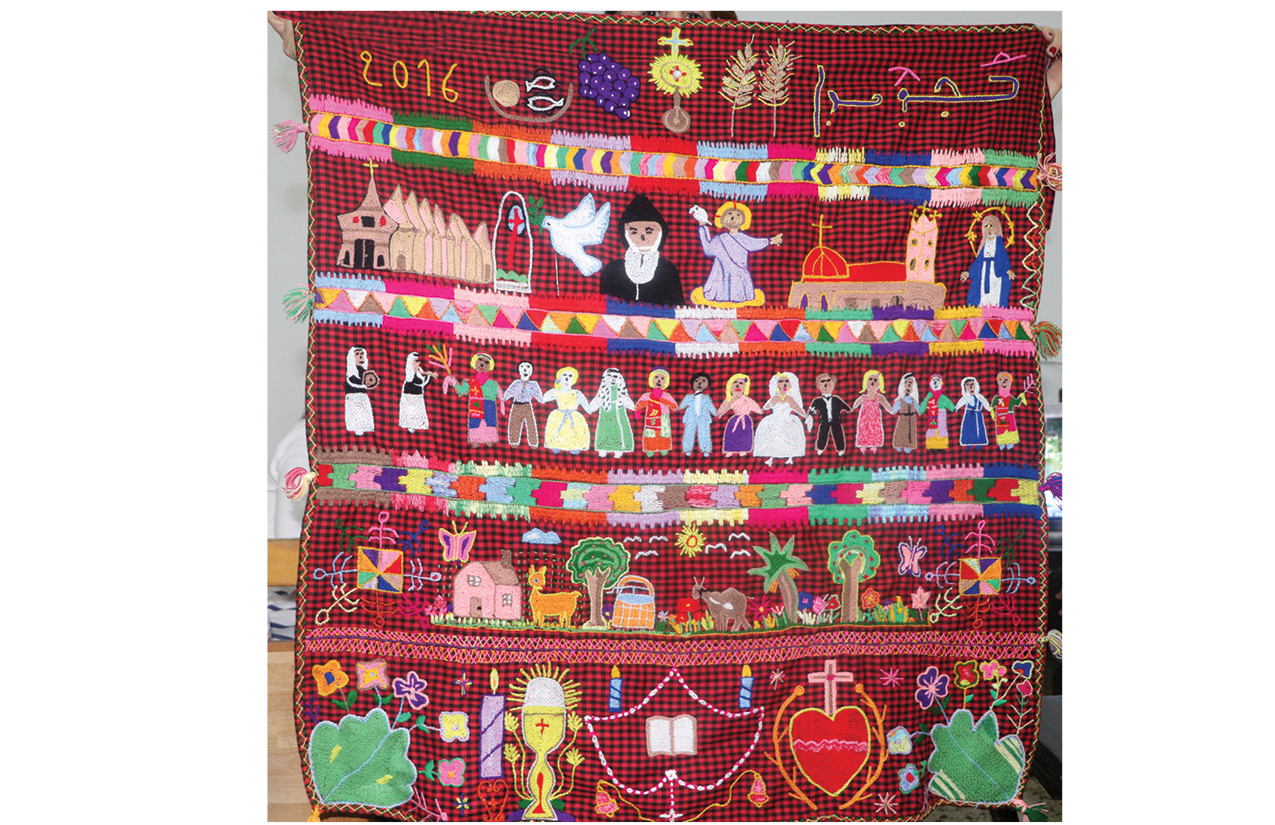

Row 2 shows the Church of Sts. Behnam and Sara, at left, and the Church of al-Tahira, with its red roof, the largest church in Iraq. Both churches were damaged by ISIS. Among the figures in the middle is St. Charbel Makhlouf, a Maronite monk.

Row 3 shows musicians from the town of Bashiqa and a dabke dance, with women wearing the shal.

Row 4: The pink house, with a well and fruit trees, is Hana’s own.

Row 5: Below three colorful lines crossing the dress, the last line is monochromatic, symbolizing Hana’s exile. “Life will never be as colorful as it once was,” she said, “but it will continue.”

(Credit: Stephanie Saldaña)

And there it was. Her dress. The shal. Already I could see threaded colors emerging. She was holding it inside out, so that as she unfolded it, I could glimpse what looked like scribbles: the outlines of what might be figures in pink and blue, purple and yellow, a deep shade of green; some pompoms of varied colors hanging on each corner; what almost looked like train tracks of alternating shades. She held it gingerly, still unfolding it, and with each unfolding more colors and figures leapt out—what might be trees, a heart—all of it still inside out and so giving the impression of a child’s drawing scribbled onto fabric. Finally the square unfolded in half, and as the center of the dress was half-revealed all was color—a line of triangles spanning the dress, the etchings of what looked like figures dancing.

I cannot tell you what even that glimpse felt like—for until then the room had been so heavy, and now into it had erupted this color. She turned the square around, until the front of the shal was finally facing me. Images came into focus: two embroidered churches. A house, a line of costumed human figures extending across the dress, holding hands and dancing. Trees. Animals. A word in a foreign alphabet. A saint. A well filled up to the brim with water.

Meena whispered: “This is our history.”

It took me a moment before I responded: “But how do you read it?”

Meena’s mother pointed to the top right corner, where she had sewn a word in Syriac in purple thread rimmed with yellow. “Baghdeda,” Hana read out loud. “The name of our town.”

“But you’re not from Qaraqosh?”

Meena whispered: “This is our history.”

She smiled. “Qaraqosh is the Turkish name for our town—what others call it. But we call it by its ancient name: Baghdeda. You’ll see that I wrote it in Syriac letters.”

Hana continued, moving from right to left. She paused at two sheaves of wheat, sewn side by side on pale lavender stalks. To its left was a shining golden monstrance holding a Communion host, and farther left was a bunch of grapes, bursting out of the fabric in rich purple. Finally, two fish and a loaf of bread rested in a basket, a reminder of the scene in the Gospels when Jesus multiplied food for a crowd.

“Everyone in Baghdeda was Christian,” she said. “The wheat and grapes might symbolize the bread and the wine used in the Mass, but my father—may his soul rest in peace—was also a farmer. We grew grapes and wheat at my home when I was growing up.”

In the upper left-hand corner, a name had been carefully sewn in Arabic, along with a date: 2016, that very year.

“That’s my name: Hana,” she said. “I sewed it in Arabic because all of us also studied Arabic. We lived close to Mosul, and so we had to know how to read and write in Arabic. I was a schoolteacher.”

“And the date?”

“That was when I finished the dress,” Hana replied. “We had already escaped from Qaraqosh to Kurdistan. I understood by then that we would have to leave Iraq forever. I thought that this was something that I could carry with me. I started sewing there, for two months. I finished it here, in Amman, just a few weeks ago.”

She pointed to the second church, shaped like a star.

My eyes settled on two large churches sewn into the center of the dress. The first had been stitched in great detail: a pink tower with what looked like a space for a clock, three golden crosses embroidered on top, and a long red roof with a dome on the opposite end.

“That’s the Church of al-Tahira,” she said. “That was the largest church in Baghdeda. Actually, it was the largest church in all of Iraq.”

She pointed to the second church, shaped like a star. “That’s the Church of Saints Mar Behnam and Sara.”

We continued down to the third panel. A series of dancers spanned the width of the dress. “That’s the dabke: what we danced for any joyous occasion,” she said.

It was such an act of attention: earrings and shoes, handkerchiefs, hands clasping one another. My eyes moved down the fabric to what appeared to be an almost fairytale-like pink cottage. Rain fell from a cloud above.

It was late into the night when we said goodbye and I walked into the cold streets alone. I had tried to write down all the details in my notebook, but I had not even thought to write down Hana’s last name. Then I remembered that she had sewn it into her dress, and I had taken a photograph.

I returned to Jerusalem, to my husband and two sons. To singing my 1-year-old daughter to sleep. To books in the library and bedtimes and bowls of cereal. Months passed. But the dress would not leave me.

Author’s note: Today, thousands of the inhabitants of Qaraqosh have returned to their homes in Iraq, where the political situation remains fragile. Thousands of others, like Hana, are resettled in countries around the world. Pope Francis visited Qaraqosh in 2021 during his pastoral visit to Iraq.

You can find all of America Media’s past Cover Stories here.