“It was like something out of a Tom Wolfe novel.” So began an opinion piece on the Trump-Biden presidential debate in The New York Post this past Saturday. Why would Tom Wolfe come up now, six years after his death in 2018? That the author didn’t need to explain why—or even who Wolfe was—is itself a testament to the outsized role the journalist-novelist played in American culture for more than 50 years.

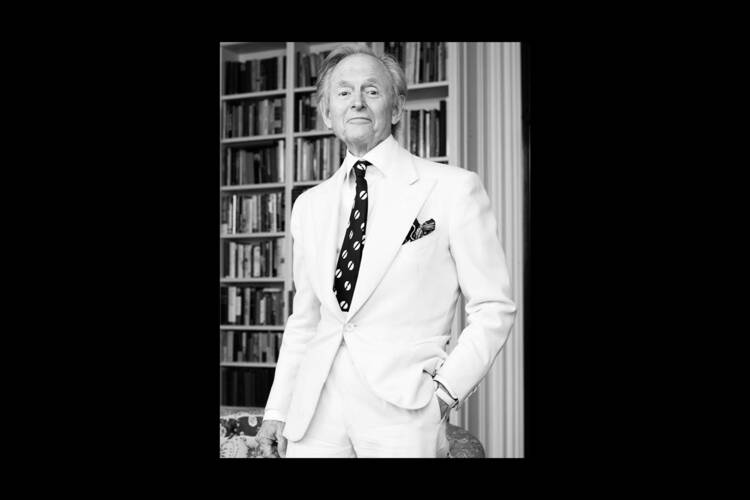

Seemingly forever bedecked in a white suit (he said that he wore one all the time once he realized how much it annoyed people), Wolfe was sui generis to the last, and bridged eras in both journalism and fiction by appropriating the techniques of one for the other. What does that mean? Like others identified with "The New Journalism" in the 1960s and 1970s, he brought some of the tropes of fiction writing to the often staid world of reporting; and in his later career as a novelist, he was both praised and criticized for incorporating a journalistic, reportorial style in his fiction.

Throughout his career, Wolfe also proved remarkably adept at skewering American elites for their affectations, lifestyles and pursuit of financial and social advantage. In a society he depicted as increasingly unmoored from its traditional supports, Wolfe portrayed status as the new focus of the American Dream, and the protagonists of his novels never stopped seeking it.

That more than anything explains why he would be invoked after last week’s presidential debate between what Wolfe would immediately have described as two “masters of the universe.” Wolfe would have loved to write about a debate between a billionaire former president who is also a convicted felon and an octogenarian sitting president whose public mental lapses are vociferously denied by many of his own confidantes. It’s a classic Wolfe plotline, involving crime, finance, high society, a touch of sleazy sexual content and a whole lot of behind-the-scenes maneuvering.

Born in 1930 in Richmond, Va., Wolfe graduated from Washington and Lee University in 1951. An attempt at a professional baseball career included a rather brief tryout with the then-New York Giants (“I couldn’t throw fastballs,” Wolfe later wrote). He received his doctorate in American Studies from Yale University in 1957. A year before, he had begun working as a reporter for the Springfield Union in Springfield, Mass. From 1959 to 1962, Wolfe worked for The Washington Post. He moved to the New York Herald Tribune in 1963, and also began to publish in outlets like Esquire.

His first book, a collected book of essays called The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, was published in 1965. Three years later, he published another collection of essays, The Pump House Gang, along with the book that would catapult him to initial fame: The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. The latter was a firsthand account of the travels of Ken Kesey and his collection of “Merry Pranksters,” a group of nonconformist hippies immersed in drug culture who encountered many of the most prominent members of the Beat Generation and 1960s counterculture in their LSD-fueled journeys.

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is often cited as a classic example of “The New Journalism,” a style of reportage Wolfe championed (and the title of an anthology he edited) in which reporters immersed themselves in the day-to-day lives of their subjects and even appropriated their voices and points of view. Acid Test and other examples of the style abandoned many of journalism’s traditional rules—including authorial distance and a presumed objectivity—in favor of a more vivid, stylized “you’re in the room with me” kind of nonfiction.

Not everyone was a fan, but The New Journalism’s basic precepts have formed the basis for much of modern media’s style and approach. Keep in mind there’s no such thing as Michael Moore or Dominick Dunne or reality TV or even “Fleabag” without some of the innovations of Wolfe and his ilk. Wolfe also coined phrases that have become markers for entire social realities, like “radical chic” and “the Me Decade.”

Among other nonfiction projects, Wolfe’s 1979 profile of the country’s first astronauts, The Right Stuff, further elevated his reputation and was eventually made into an award-winning film.

Only in the 1980s did Wolfe turn to fiction writing, with The Bonfire of the Vanities being serialized for over a year in Rolling Stone before being heavily revised and then published in full in 1987. The book earned numerous positive reviews for its laser-sharp depiction of the culture of 1980s New York. (A 1990 movie based on the book and directed by Brian de Palma was, to put it mildly, both an artistic and a financial trainwreck.)

In 1988, longtime America contributor Peter A. Quinn (who knows his way around New York’s corridors of power) reviewed Bonfire for the magazine. “Wolfe has not created great and memorable characters, nor has he done for New York what Dante did for heaven and hell, or Dickens for London, or Joyce for Dublin,” Quinn wrote. “Few novelists achieve such things, especially on their first try. But he has succeeded in puncturing the pretensions of The Imperial City, the air running out in something between a Bronx cheer and a long, soft hissssss.”

It took Wolfe more than a decade to write his next novel, A Man in Full, a 1998 bestseller. Though the book received positive reviews, John Updike panned it in The New Yorker, initiating a literary slugfest between the two heavyweights that eventually also drew in John Irving and Norman Mailer. (Wolfe later wrote an essay on the lot of them, “My Three Stooges,” and called Updike and Mailer “two old piles of bones.”)

A Man in Full did for Atlanta’s social scene what Bonfire did for New York—which was to dissect it, more or less. The book was just recently adapted into a Netflix miniseries earlier this year. Six years later, he came out with I Am Charlotte Simmons, which told the tale of a naive college freshman attending an elite private college: As in Wolfe’s previous novels, the primary characters are obsessed with their social standing and the possibility of winning in a world where they were born on third base.

(I took a stab at reviewing I Am Charlotte Simmons in 2005, but the review never saw the light of day. I am grateful to the editors of America for that; it didn’t age well.)

Wolfe took his typical themes to Miami society with his 2012 novel Back to Blood. It was reviewed in America by Brian Abel Ragan, who criticized Wolfe’s lack of understanding of religion in American culture (“God is not among Wolfe’s large cast of characters”) and his often-offensive depictions of women. Nevertheless, Ragan wrote, “Wolfe remains one of the writers by which our times will deserve to be remembered.”

In their 2018 obituary of Wolfe for The New York Times, Deirdre Carmody and William Grimes noted that for all that Wolfe missed in his reporting or his fiction or his criticism, he overheard an awful lot. “In the end it was his ear,” they wrote, “acute and finely tuned—that served him best and enabled him to write with perfect pitch.”

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Gaza,” by Kirby Michael Wright. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Members of the Catholic Book Club: We are taking a hiatus this summer while we retool the Catholic Book Club and pick a new selection.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

- The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

- What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

- Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

- Father Hootie McCown: Flannery O’Connor’s Jesuit bestie and spiritual advisor

- Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane