‘Dante’ and ‘Desire’: 2 poetry collections confront modern crises in ancient style

Poets are architects and builders, though their labor is often invisible and their project ignored by a society dazzled by the tangible rather than the immaterial world of verse. For the last century, those who have sustained the house that generations of poets built have conducted their business quietly, adding new rooms and remodeling old ones.

Micheal O’Siadhail’s Desire and Angela Alaimo O’Donnell’s Dear Dante are collections designed and erected meticulously in an ancient style that an avid reader is unlikely to see in much contemporary poetry. The themes of each collection, however, are defined by their relationships to modernity and humanist and spiritual thought.

Form, in all its forms, can be intimidating for the writer and reader. And yet, O’Siadhail and O’Donnell tell stories in our modern language informed by the structures of the ancients. O’Donnell’s poems are written in a combination of terza rima, an Italian meter and rhyme structure consisting mainly of three-line stanzas, and Petrarchan sonnets, both forms favored by Dante. O’Siadhail also employs terza rima and sonnets and maintains a consistent rhyme scheme.

I am only a bit ashamed to say that, though I read Dante, Milton and Homer when I was young, their structure and form were mostly lost on me. By committing to form, the poet accepts guidelines that demand creativity within confines. Just as the athlete’s prowess only exists within the rules of their sport, the formal poet must acknowledge and thrive within structures. Ancient writing structures remain impressive but elusive, though the older me has since experimented with both the challenge and the seeming freedom of restrictive forms. In Desire and Dear Dante, form serves as both homage and principle.

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell begins Dear Dante with words to live by: “All poets are liars.” Poets know this to be true, at least in the sense of Thomas Aquinas’s declaration that “every lie is a sin.” Poetry, though often informed by universal truths, relies on language to convey a reality that it cannot fully portray. The realm of poetry (and art more broadly) is built on the lie that language could ever truly mimic reality, yet its power to inform and define reality persists. O’Donnell leads us into the mind and world of Dante Alighieri, the poet whose dramatic portrayal of hell has influenced so much of our modern conception of fire and brimstone. O’Donnell depicts Dante’s inner world with a modern eye toward humanity, despite the inhumane punishment at the heart of the Divine Comedy.

Depending on your connection to Dante, Catholicism and poetry, the poems within O’Donnell’s book will either make you nod with their contemporary compassionate logic or shake your head at the torturous fates of those deemed “sinners.” We follow the poet O’Donnell, and she follows the other poet, Dante, through the realms of hell. In some ways, the text is a call and response. Inscriptions from Dante, as well as other poets, accompany each poem, detailing the fates of the sinners in each realm, though O’Donnell’s verse often feels like the truth we, as the modern audience (or at least me, a reader who loves the message of Christ without Dante’s fire and brimstone) want to believe.

Just as Dante examines the depths of hell for his audience, O’Donnell plumbs the depths of Dante to reveal his humanity, and she finds the common core of poetry: “for he knows only poetry can raise/ his harrowed soul from the deep pit of grief.” This collection is a love letter to poetry and verse as much as to Dante, though the latter probably more so.

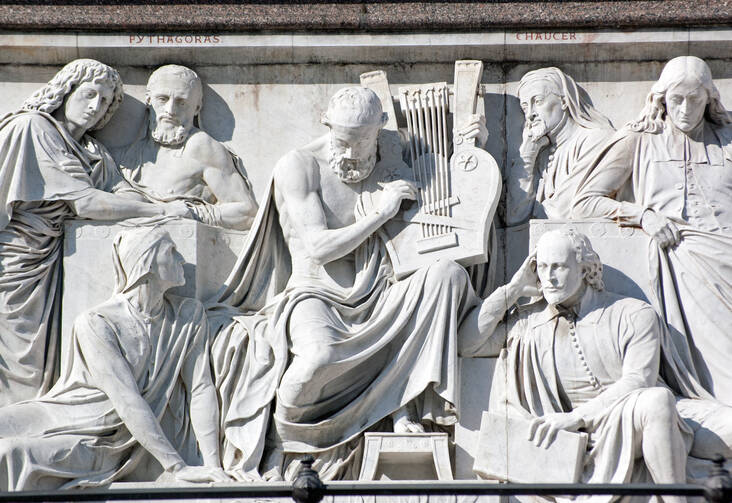

In her poem “Dante among the Poets,” when Dante’s journey through hell leads him to encounter the great pagan poets Homer, Horace and Ovid, O’Donnell believes Dante is “happy to be in hell.” Certainly that is a sin, but so too is poetry.

In “Christ in Hell,” O’Donnell considers how to portray Christ in Dante’s version of hell. It is nearly impossible to imagine a Christ who might “approve/ of punishment eternal.” After all, the figure of Christ forgives all sinners, even “his killers [...] who knew not what they do.” The poet imagines a Christ who must leave “many more” sinners behind in hell than those he rescues, and for this, “Jesus wept.” This poem speaks to one of the fundamental issues of the hell that Dante imagines and the concept of eternal punishment more broadly. In the figure of Christ, we find eternal forgiveness, so who is the arbiter of such punishment, and is such punishment befitting any crime on earth?

In “Dante among the Lovers,” O’Donnell’s Dante encounters the lustful, who are whipped endlessly by a cloud of dust to imitate how they allowed passion to dominate their piety. Here Dante is heartbroken for the fates of those who he understands as having loved too greatly on earth. He resists judgment for the sinners and instead turns it back on God: “The balance sheet/ God keeps appalls his human heart.” Rightfully so, we humans might say: What a seeming design flaw to allow humans access to pleasure and lust and then ask them to deny it. The “balance sheet” feels punitive (it is, obviously), and unnecessary for such a crime. Dante’s reaction mimics our own, and he “faints from grief.”

“Dante among the Suicides,” imagines Dante’s judgment of God and not the sinner: “in Dante’s chest is a heart like ours, birthplace/ of love for the sinner in the face/ of sin.” The forest of suicides in Dante’s Inferno is perhaps the most gruesome punishment, which posits that harm against oneself is worse than harm against others. O’Donnell does not allow Dante to merely witness this, however. Dante feels the sting of injustice at this punishment for those who saw no other way out, who realized “none of us can win.” O’Donnell’s Dante questions the decisions of God, not the sinner.

Micheal O’Siadhail’s Desire does not deal with the abstractions of the afterlife and punishment but with the corporeal, natural and technological phenomena that have irreparably changed humanity in the pandemic and post-pandemic era. What us most intriguing about O’Siadhail’s verse is its clear language and intent, despite the elaborate forms it appears in.

With that combination of language and form, the collection presents itself as a simple, humble man living in an extravagant Victorian mansion. The chapters are titled, but the separate poems are numbered as if each is not nearly as important as the sum of its parts, which is exactly what O’Siadhail seeks to unveil with his epic examination of the present: Our inability to see ourselves within the larger context of the universe, the world, our community, is our downfall.

Each of the chapters details a major issue and how humanity has failed to face it adequately but also offers simple teachings on the possibility of growth and renewal. “Pest” discusses the Covid-19 pandemic and how the “nettedness that bound us one and all” should have forced us to take stock of how interconnected we are. “Habitat” confronts climate change and consumerism, acknowledging the absurdity of our consumption (“We create demands we then supply”), our lack of political will and the need for swift action. “Behind the Screen” details our relationship to technology, framed by the story of Satan’s temptation of Adam and Eve (“Tragedy of that one apple’s fall/ Our first garden’s greed to know it all.”).

“Desiring,” the third poem of the penultimate chapter, is an examination of humanity’s obsessed materialism. O’Siadhail describes our separation from the natural rhythms of the world: “Ungrounded in our seasons all is speed/ Measured out in minutes hastening by;/ Time is money seconds count in greed.” He goes on to connect us further to the universe: “Eons we forget deep in our bones/ Borrowed from the stars our carbon dust—/ Yet such damage our small age condones/ And so much destroyed left us in trust.” Our neglect and disgrace, O’Siadhail argues, are products of our collective forgetfulness. We choose to center ourselves as individuals and forget the collective.

Readers do not need to look far within Desire to find O’Siadhail’s interpretation of the anticapitalist and anti-consumerist roots of Christianity. In the fourth poem of “Desiring,” O’Siadhail provides facts, “One percent owns over half the wealth,” accompanied by pleas to remember our purpose, “Thriving is no zero sum./ Stewards of God’s sacred earth we care/ For our children’s children; seeds we bear.” Indeed, to alleviate collective suffering and save the earth for future generations we must sacrifice a little of our own material needs. As stewards, our duty is to nurture, yet we have taken to nurturing our greed and comfort at the expense of everything else.

Desire is a collection of our time, written in a way that is, in a sense, out of time. Though the poems are specific to 2020-24, the lessons O’Siadhail offers are timeless. They are the enduring lessons of great spiritual traditions: Do not take more than you need, give what you have, remember your place in the universe and consider others as much as yourself.