July 14 is the feast day of St. Kateri Tekakwitha. I attended Mass this past Sunday in a parish that has a statue on its grounds—in Southern California, mind you, a long way from Auriesville, N.Y.—of the famous “Lily of the Mohawks,” who was canonized in 2012. Some of the founding editors of America, including the first editor in chief, John J. Wynne, S.J., were among the early promoters of her cause for sainthood. Many mentions of her in the magazine’s early years included a 1939 poem, “Kateri Tekakwitha,” by a young Jesuit, Walter J. Ong.

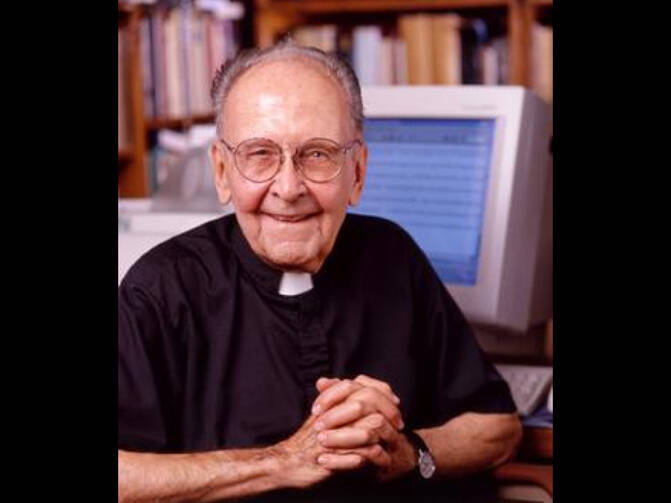

Ong had entered the Jesuits only four years before. His professional poetry career didn’t last long, but that turned out for the best: Father Ong’s contributions to American letters over the next six decades were countless, and he remains a renowned figure in the study of communications, literacy, group psychology and mass media. His books Orality and Literacy and The Presence of the Word remain classics decades after their publication.

Focusing in his academic work on language acquisition and production in both the primitive and second-order sense, Ong was one of the first to note the ways that mass media (largely television in his mind, but he all but mapped out what the internet would become) had created a new kind of literacy, for better or for worse; new jargons and modes of expression, he pointed out, were changing the landscape of communication in numerous areas of human endeavor. (I was startled to discover in graduate school that some of my peers who cared not a whit about Christianity or the church nevertheless were huge devotees of Ong, including many a computer wonk.)

As Nick Ripatrazone noted in a 2017 article for America on Ong, Marshall McLuhan and Andy Warhol, Ong’s study of literacy from its primitive beginnings gave him particular insight into the digital world we live in now. “The fragmentation of consciousness initiated by the alphabet has in turn been countered by the electronic media which have made man present to himself across the globe, creating an intensity of self-possession on the part of the human race which is a new, and at times an upsetting, experience,” Ripatrazone quoted Ong. “Further transmutations lie ahead.”

“Father Ong wove his theological, psychological and philosophical insights to show the contrasts he saw between morality and literacy,” wrote Wolfgang Saxon in a 2003 obituary in The New York Times. “He was considered an outstanding postmodern theorist, whose ideas spawned college courses and were used to analyze anything from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s soaring oratory to subway graffiti.”

Born in 1912 in Kansas City, Mo., Ong graduated from Rockhurst College (now Rockhurst University) in his home town in 1933, entering the Jesuits two years later. He was a bit of a prodigy from the start—his master’s thesis on Gerard Manley Hopkins was supervised by McLuhan himself. Ong’s wide-ranging and insightful 1941 essay for America, “Mickey Mouse and Americanism,” surely started life as a graduate paper or thesis. He examined the role the anthropomorphic cartoon rodent played in our national consciousness—and asked why Mickey Mouse was treated so uncritically despite his ubiquitous presence in American culture.

The essay was written five years before he was ordained a priest in 1946 and 14 years before he received his doctorate in English from Harvard University. (Among its insights: the troubling fact that Mickey Mouse’s best friend is a dog named Goofy—also known as “Dippy Dawg” in those days—and yet Mickey also keeps a different dog, Pluto, as a pet.)

After receiving his doctorate, Ong taught in various capacities at St. Louis University for the next 36 years. His students referred to his intellectually challenging and sometimes idiosyncratic classroom offerings as “Onglish.” He also served as a professor of psychiatry (!!!) at the university’s medical school. In 1966, he was appointed to President Lyndon Johnson’s White House Task Force on Education. He also served as the president of the Modern Language Association of America in 1978.

Over the course of his career, Ong published over 450 articles and a dozen books. I suspect that every communications professor on earth has 2002’s hefty tome, An Ong Reader, on the office shelf.

In 1996, Ong wrote a long essay for America asking “Do We Live in a Post-Christian Age?” It is classic Ong, erudite and insightful and occasionally cutting. He wrote of the long processes of evolution and physical transformation that had prepared the world for the coming of Christ, sounding more like Teilhard de Chardin or William Lynch than a scholar of literacy and communications. And noting that by “post-Christian” most people meant “post-Christendom,” he wrote the following:

The apotheosis of the Christendom mentality is found in the bumptious and now grossly distasteful proclamation of Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953), his most quoted and, until recently, most generally relished saying: “The Church is Europe, and Europe is the Church.” Europe is not the church, and, far from being post-Christian, most of the world is still pre-Christian (which is not to say pre-Eurochristian) in the sense that it has not yet had Christian revelation effectively proclaimed to it, so that individuals in it have not ever been able to choose between being Christian or not.

Father Ong died in St. Louis in 2003 at the age of 90. In a retrospective published a year later, Paul A. Soukup, S.J., noted Ong’s enormous contributions to the field of communication studies. “From the perspective of an interest in connections among many areas of human knowledge over such a long career, he explored a whole gamut of activities by careful observations of the threads that run through western culture and by insightful analysis of what he observed,” Soukup wrote. “Communication forms one of those many threads in the West—perhaps the dominant one—and so it occupies a similar place in Ong’s work.” Ong, he noted, also made four valuable contributions to the field of communications:

First, as a cultural historian exploring rhetoric, he has called attention to the link between mental processes and communication tools. Second, in his recognition of the visualism promoted by printed texts, he reminds us of the role of the sensorium in all communication. Third, through his proposal that we think of the modes of communication (primary oral, literate, secondary oral) as stages building on one another, he has helped to identify the extraordinary complexity of human communication and provided an hypothesis to guide further exploration. And, fourth, by his insistence on the living word, he has kept the human at the center of all communication, reinforcing the link between the interpersonal and any other kind of mediated communication.

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Kateri Tekakwitha,” by Walter Ong, S.J. It first appeared in America in 1939. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Members of the Catholic Book Club: We are taking a hiatus this summer while we retool the Catholic Book Club and pick a new selection.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Father Hootie McCown: Flannery O’Connor’s Jesuit bestie and spiritual advisor

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane