The years after World War II in Europe were a time of great darkness and devastating loss, rationing and deprivation and a profound longing for better times. History reveals many instances when hope and determination have renewed and reunited our world after such difficult experiences. One enduring example is the Edinburgh International Festival. Founded in 1947, during a period of grim post-war austerity, the festival was intended by its founders to help reunify a shattered Europe by harnessing the power of great art.

The first program, in August and early September of that year, included a broad range of performing arts, including choral and orchestral music, opera, ballet, drama and film. It also hosted, in a foretaste of what would become another Edinburgh summer fixture, a program of Scottish pipes and drums with marching military bands accompanied by traditional Highland dancing. That musical spectacle was conducted on the open esplanade of Edinburgh Castle, a royal and military fortress since the mid-11th century, built atop the craggy plug of an extinct volcano almost 500 feet above the city.

It was not long until the international festival, which has taken place continuously ever since other than the Covid-19 pandemic year of 2020, parented a slew of secondary events, still presented in these same long northern summer days. Most are now well established in their own right in and around the city. Maybe you have heard of the Fringe?

Festival lore tells of how, back in 1947, eight theater groups turned up unannounced to perform at the first “official” festival. More and more groups showed up in the following years until a formal “Fringe Society” was set up to coordinate this rather anarchic array of independent performers arriving in the capital each summer. They still do.

If the “official” international festival tends towards the mainstream (although there is much that is exotic and unstuffy in this year’s program), the Fringe’s over 3,000 discrete shows, trying to catch the zeitgeist, performing in almost every available space around the city, lean towards the avant-garde, experimental and, sometimes, the just plain weird.

Nowadays, it is correct to refer to the festivals in the plural because there are so many. The city also plays host to the massive Edinburgh Book Festival, the Edinburgh Art Festival and many more. One event, the Edinburgh International Film Festival, also launched in 1947, is said to be the oldest continuous cinema festival in the world.

In 2018, some Christian leaders in Edinburgh discussed a shared concern that faith was not so visible in this extravaganza of simultaneous festivals—an absence especially striking in a city of many fine churches and vigorous intellectual debate, the seat of the Scottish Renaissance as well as the Scottish Reformation. They determined to launch the Edinburgh Festival of the Sacred Arts, seeking to reclaim a place for Christian faith in human culture and put faith back into the festival season.

Significantly, the organizers have enrolled this celebration of sacred arts within the Fringe festival, placing it alongside its varied secular performances rather than establishing the sacred as art on the outside, peering into the wider culture. The Edinburgh Jesuits are part of the cooperative group that prepares and presents this program, now an annual event as well.

The director of the festival is the Rev. Gordon Graham, whose distinguished academic career as a philosopher, author and Episcopal priest has included teaching positions at the universities of St Andrews and Aberdeen and at Princeton Theological Seminary (2006-18). Speaking to America, Rev. Graham remarked that “Christianity’s contribution to music, poetry, painting, architecture, dance and drama is immense.”

He and his fellow faith leaders who began the sacred arts effort hoped “to enable city-center churches of all denominations to celebrate their heritage and mission in a way that contributes significantly to the internationally acclaimed Festival season in Edinburgh.”

“Its aspiration,” he said, “is to be a compelling intersection between faith and art.”

It is that “compelling intersection” that attracted the Jesuit city church in Edinburgh to engage with this latest addition to the festival season. The splendid neo-classical Edinburgh Jesuit Church of the Sacred Heart (1860) occupies a central location in the city and already has links to the larger festival and to the Fringe program, leasing some of the facilities to a Fringe promoter. Why? From the earliest days, Jesuits have engaged with the arts and culture widely.

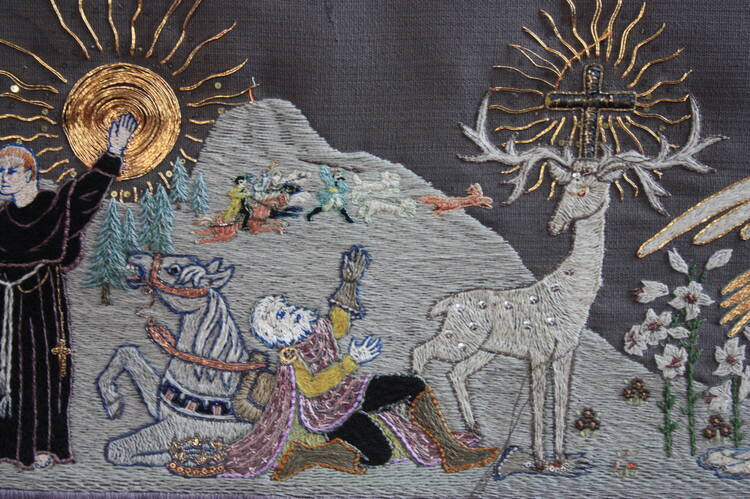

The late and much-loved Jesuit historian John O’Malley has left us a wonderful survey of the remarkable Jesuit commitment to the arts, from the Society’s foundation in 1540 until its suppression in 1773. For Father O’Malley, cited on the Irish Jesuits’ website, “The Society of Jesus was probably the most prolific patron of the arts in the Baroque era.”

The director of the Jesuit Centre and church pastor Adrian Porter, S.J., remarks that “Jesuit cultural and artistic engagement with the arts really derives firstly from the conviction that Ignatius bequeathed to us, that it is possible for us to seek and to find God in all things; from that moment, we come to see that the arts, as they probe for expression of ultimate truth and beauty, are fully complementary activities that we can celebrate and promote.”

The Sacred Arts program for 2024, launching a week after the official festival and the Fringe festival and performed in nine city-center churches (including the Jesuit church), encompasses a range of genres. It opens and closes with worship on Aug. 11 and Aug. 17.

The program explores the sacred in visual arts and music in various forms ranging from Faurė and Bernstein (Aug. 14) to modern jazz (Aug. 12). It looks at the sacred in cinema (Aug. 16) and offers guided tours of participating churches and readings of Scottish religious poetry from the Middle Ages to present times (Aug. 11).

A thrilling innovation this year has been a competition for young composers of sacred music; the winning submissions from this new generation of composers will be performed on Aug. 15 at the famous Canongate Kirk, where British monarchs worship when they come to Edinburgh.

Our times have been marked by a poisonous mix of religious hatred, increasingly exacerbated by social media, as witnessed south of Edinburgh in England in recent days where right-wing riots were instigated by waves of A.I.-enabled disinformation. The hostility to faith exists incongruously with widespread religious ignorance and a vast practical loss of faith. Europe forgot about faith and now worships other deities.

In the center of Edinburgh, described since the 18th century as “The Athens of the North,” large statues of David Hume and Adam Smith frown over the heady proceedings each August as this dour city goes a bit wild. The reformer John Knox has his unsmiling statue nearby in the courtyard of New College, where the study of divinity continues an academic tradition that began in 1583. Renowned Scots poet Hugh MacDiarmid wrote of the Scottish capital as “a mad god’s dream/fitful and dark.” In so many ways, this is the place and the time for what the Sacred Arts festival hopes to offer this city.

So often the best of humanity shines forth in the arts. Performance of word and music, dance, painting and drawing and, increasingly, the new creative forms that the digital revolution is advancing all have the power to show us at our best. People of faith, not least those familiar with the Ignatian tradition, know that the best of humanity will reveal God to us. Our city and our world need the power of the arts and the power of faith, never as an escape from the world, but to bring us back to living life to the fullest in peace and fraternity.