A Homily for the Twentieth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Readings: Proverbs 9:1-6 Ephesians 5:15-20 John 6:51-58

Toward the close of his masterpiece Being and Time (1927), the great German philosopher Martin Heidegger raised a question that would become fertile ground for science fiction. Why does time only run forward? Why can’t it go backward?

Heidegger’s answer was, of course, nigh impenetrable but also rather poignant. Translated and simplified he said: because all our hopes and desires lie in the future. Everything we want in life lies ahead of us. It would be meaningless for us to go back.

Granted, we can be found waxing nostalgic for days that are past, especially as we near death. “Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away…” Yet Heidegger would insist that even then the human heart is longing, looking ahead, for something it has never known: fulfillment.

Edith Stein was born into an observant Jewish family in what was, in 1891, the German city of Breslau. By her teenage years, she had become agnostic, and fulfillment for Edith seemed to come in the form of higher education. In 1916, she gained a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Freiburg and was made an assistant of another great German philosopher, Edmund Husserl.

Edith Stein was moving forward at a rapid pace, and as Heidegger insisted, what other direction was there? To be human is to hunger for the future, constantly to look ahead for what is to come, always searching for something that never quite arrives.

Academics are expected to be avid readers, and Edith was no exception. A feminist before the term existed, she even read a book she found on a friend’s shelf, the autobiography of the Carmelite saint and doctor of the church, Teresa of Ávila. Before the modern era, where else could one turn to hear the voice of women? Like others in the Carmelite tradition, Teresa of Ávila insisted that union with God, true fulfillment, is something that can be obtained before we die.

The same theme runs through the writings of St. John the Evangelist. We call it realized eschatology: Eternal life begins when one truly gives oneself to Christ. Put another way, the only thing that keeps us from complete fulfillment is radical commitment. They stand in a direct relationship.

I am the living bread that came down from heaven;

whoever eats this bread will live forever;

and the bread that I will give

is my flesh for the life of the world (Jn 6:51).

In prayer, each time we pause our words and meditations simply to be aware of God’s presence—we call this contemplation—we realize, for just a moment, that we are in union with God, that we have found fulfillment. It is fleeting on this side of the grave but nonetheless real.

Edith Stein had had little involvement with Catholics, though her philosophical work involved some study, and even translation of, Thomas Aquinas. On a sightseeing trip to the cathedral in Freiburg, she recorded seeing a young Catholic woman, her arms loaded with groceries, enter the church to pray before the Blessed Sacrament. It seemed to the young professor that there must be something quite real about the place—in the place? All the Protestant churches and synagogues that she knew of were locked during the week.

Edith read Teresa of Ávila through the night. When she finished, she closed the book, saying to herself, “This is the truth.” What she suspected to be so real about the cathedral that she had visited was the truth, and the truth was a person.

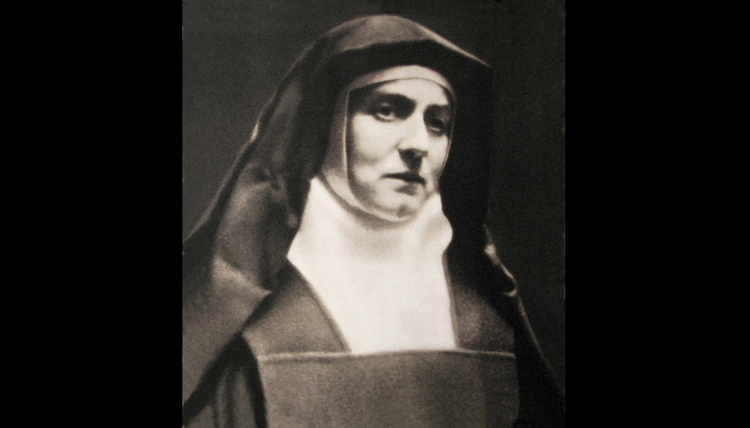

Her conversion to Catholicism followed, and not long after, she chose to follow St. Teresa of Ávila into the Carmelite life, becoming Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross in the Carmel of Cologne. Fearing for her safety under Nazi rule, her superiors arranged a transfer for Sister Teresa Benedicta to a Carmel in the Netherlands. They also arranged for her sister Rosa, though a laywoman, to join her there.

When the Dutch bishops protested in print against Nazi antisemitism, the Nazis responded by rounding up Jewish converts to the Catholic faith, who had previously been spared. On Aug. 2, 1942, Sister Teresa Benedicta and her sister Rosa were removed from the Carmel. The Carmelites recorded her saying, “Come, Rosa, we’re going for our people.” They both died later that month in Auschwitz.

Time only moves forward because that is where all our hopes lie. It cannot go backward. Neither can we. The great question for each of us is what lies in store, ahead of us. Will we ever be able to close a book, find a relationship, enter a new way of life, when we can simply say to ourselves, “This is the truth”? It depends. On two things. What we find and what we are willing to give for it.