Review: Tim Kaine reminds us what’s possible in a political candidate

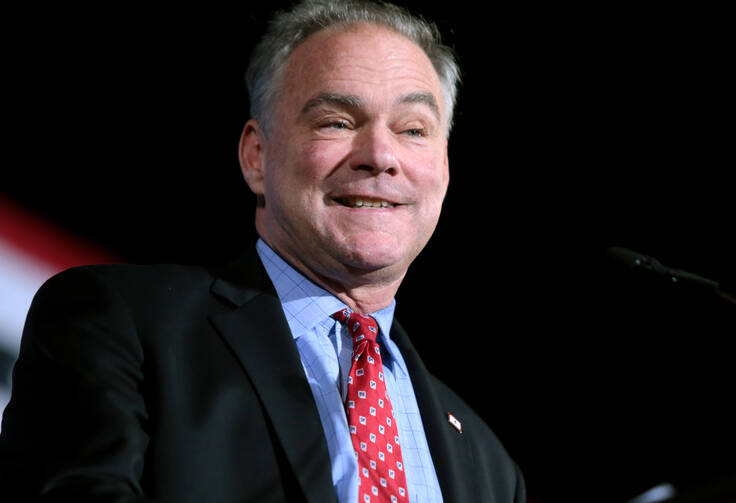

As we suffer through another season of presidential politics, along comes a memoir from a man who once seemed like a fantasy candidate: a decent dad with strong values, good diction and keen intelligence. Senator Tim Kaine, who was on the ballot as Hillary Clinton’s running mate in 2016, stands out as one of the most virtuous people ever to run on a national ticket, in the same class as Jimmy Carter, Mitt Romney and Barack Obama. A friendly neighbor with kindness and brains. In this season of dismay, Kaine reminds us what is possible in a big-ticket candidate.

In Walk Ride Paddle: A Life Outside, Kaine invites readers on a journey as he narrates his human-powered travels throughout Virginia, where he has served as senator, governor and mayor of Richmond.

Between 2019 and 2021, Kaine hiked 559 miles of the Appalachian Trail, cycled 321 miles along the crest of the Virginia Blue Ridge Mountains and canoed the James River from its headwaters in the Allegheny Mountains to the Chesapeake Bay.

Today, as it has always been, America is beautiful, adorned with lakes and mountains and crossed by trails and rivers. If you want to find yourself (and your country), put a foot out the front door and keep going. No wonder the travel memoir is a great American genre, from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America and William Least Heat-Moon’s Blue Highwaysto more recent incarnations like Rinker Buck’s Life on the Mississippi and Neil King’s American Ramble.

Kaine needs this trip because he is middle-aged, “life is filled with pressure,” and his vocation, politics, “seems more and more like an NHL game—point-scoring surrounded by a crowd that’s ready to fight.”

And, of course, there’s the presidency, the Jan. 6 insurrection and nowthe third candidacy of Donald Trump. Kaine’s vice-presidential run convinced him that he does not want to go higher in national politics. He wants to go deeper. “National politics is increasingly a branch of the entertainment industrial complex; a world that doesn’t fit me,” he writes. “How can I moor my future public service to something more meaningful?” So Kaine hops a train from Union Station in Washington, D.C., to Harpers Ferry, W.Va., to hike south on the Appalachian Trail.

Like any good traveloguer, Kaine tells us about the history of places he passes through, including the John Brown raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859. Brown, an abolitionist, tried to start a revolt among enslaved peoples by hijacking a U.S. government arsenal with 22 followers. They were defeated by U.S. Marines led by Robert E. Lee. Brown was captured and executed.

The Civil War, whose battlefields litter Virginia, is a constant theme throughout the book. That is welcome. History is interesting and important.

But history is also a little too safe.

What is missing from Travels With Tim is a hard confrontation with what ails America today. Trump did not win just because of strongman charisma and nightclub-level comic timing. He won because millions of people in the region Kaine is walking, biking and paddling through are grieving lost prosperity and saw in Trump a rebuke to elite people like Kaine. In 2016 and 2020 and 2024, these voters have felt maligned by trade deals, a tech revolution, low wages and anti-worker policies, and did not think Democrats had good enough answers. I was hoping for a book peopled by these characters, by Kaine’s enemies as well as his friends. But that isn’t the case.

The Catholic Church is an important part of Kaine’s identity. He attended Rockhurst High School, a Jesuit school in Kansas City. He reverently quotes Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J. (“The world is charged with the grandeur of God”) and professes a love for Catholic social teaching. After his first year at Harvard Law School, Kaine took a year off to volunteer with the Jesuits in Honduras as part of the Jesuit Volunteer Corps. His dad had owned an ironworking shop when Kaine was growing up, and Kaine taught basic carpentry and ironwork to teenage boys in Honduras. That country, he notes, showed him Jesus. “I saw how poor Hondurans helped each other deal with adversity that seems unimaginable to me,” he writes. “Church provides a place to share burdens and joys, welcome life, and mourn death.”

But there is pain and suffering in America as bad as that in Honduras. The mystery of our existence is that the grandeur of God is suffused with so much heartache. America is beautiful, loving and funny, but it is also ugly, tortured and awful; and a serious writer, especially a Catholic, should play all the notes. Kaine does not always succeed here.

When traveling through small-town America, let us please name more specifically the current cruelties along with the charms: the corporations like Walmart and Amazon that don’t pay their workers enough to send their children to college; the hospitals and doctors that, like those colleges, abuse their monopolistic pricing power to price-gouge; the industries that still pollute rivers. All are as real as the soaring Blue Ridge Mountains and the spacious James River.

We should always, when possible, vote for reverence, curiosity and kindness, but political leaders should earn the power we give them by naming and dissecting our problems in accurate and painful detail. To paraphrase a line attributed to Karl Barth about preachers, if you’re going on a journey to discover the soul of America, carry a newspaper in one hand—and a cross in the other.