Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in America on March 6, 1971, titled “Jesus and Our Search for Security.”

In a church in Southern England one can visit the tomb of a certain Sarah Fletcher who—according to her epitaph—died “a martyr of excessive sensibility.” This high-sounding phrase conceals the straightforward fact that her husband mistreated her and she hanged herself. Many readers of modern theology may feel that the basic facts about Christian faith are being often hidden behind similar lofty phrases and that they themselves have become the martyrs of excessive academic refinement. Debates about collegiality, eschatology, hermeneutics and political theology can turn into a source of bewilderment, if not exasperation.

Faced with these latter-day theological controversies, some Christians seek relief in the person of the historical Jesus. The Sermon on the Mount, the parables of the Kingdom, Jesus’ demand for absolute obedience to the divine will and His unswerving love in taking the road to Jerusalem and Calvary—all this forms an uncomplicated challenge and consolation for us. Surely the story told by the Synoptic Gospels provides peace and security in the face of theological turmoil. And yet, concentration on Jesus of Nazareth may in fact do nothing to offset and much to accentuate one’s bewilderment.

The pursuit of knowledge about the historical Jesus raises questions which have not proved amenable to easy answers. Can we establish very much about the life of Jesus? To what extent have later commentary and interpretation “overlaid” His story—even as it is presented by the Synoptic Gospels? In any case does it really matter in principle how much or how little investigation can settle about the history of Jesus of Nazareth? Was Kierkegaard correct in maintaining that “If the contemporary generation of Jesus had left nothing behind them but these words: ‘We have believed that in such and such a year God appeared among us in the humble figure of a servant, that He lived and taught in our community, and finally died,’ it would be more than enough”?

For nearly two centuries replies to these and further questions have been offered by innumerable scholarly and popular works on the historical Jesus. From that mass of literature certain morals may be drained off. First, Jesus must not be turned into a contemporary. He is rightly viewed within the historical framework of the first century. To describe Him as a revolutionary leader, a truly secular man or the first hippie may be emotionally satisfying, but for the most part these stereotypes are intellectually worthless. Albert Schweitzer’s warnings against creating Jesus in accordance with one’s own character still stand.

Second, our sources do not permit us to write a biography of Jesus. Our knowledge of Him is practically restricted to the last two or three years of His life. Even for these years very little chronology can be established. The sources we possess make it notoriously difficult to penetrate His inner life.

Third, we need to respect the nature of the Gospels as brief testimonials of faith. For the Synoptic writers, no less than for St. John, Jesus has become the central object of religious devotion. They offer an amalgam of believing witness and historical reminiscence with the aim of eliciting and developing the reader’s own faith. The Gospels may not be dismissed as nothing more than the devotional literature of the early Church. Yet neither should they be interpreted as ordinary historical sources from ancient times.

These and other lessons to be drawn from modern research caution us against seeking easy solutions to our contemporary problems by a simple appeal to the figure of Jesus. Even in the Synoptic Gospels there is no zone of untroubled security to be found. On the other hand, we ought not to disregard or trivialize the historical existence of Jesus. His life has proved and remains an essential factor for Christian faith. His death and resurrection form, it is true, the high point of divine revelation, but not in such a way that His earthly career is rendered a matter of indifference, a mere prolegomenon to be relegated to the history of Judaism. The particularity of His human life demands respectful attention. Both the Synoptic account of the preacher from Nazareth and Paul’s reflections on his Lord’s death and resurrection belong within the canon of scripture. The history of Jesus is neither theologically neutral nor theologically paramount.

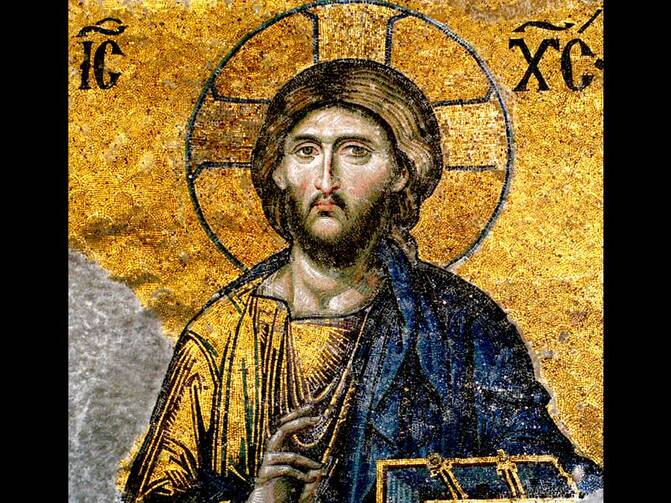

In brief, the proper tension between the concreteness of a given human life and the universality of Christ’s lordship must not be relaxed by devaluing either past origins or present experience. We meet God in the cosmic Christ who encounters us now, as well as in the strangeness of a first-century Galilean whose preaching resulted in His crucifixion.

I hope that these reflections do not conceal behind lofty phrases the simple, if profound, link between Christian faith and the historical Jesus. They are intended as a warning against any facile expectation that recourse to Jesus of Nazareth will quickly solve our bewilderments.