Shakespeare, Herman Melville used to say, was a sort of god of literature—high praise, and from an authoritative source. In 1848, at the age of 29, Melville wrote of the Bard: “Ah, he’s full of sermons-on-the-mount, and gentle, ay, almost as Jesus. I take such men to be inspired. I fancy this Shakespeare in heaven ranks with Gabriel, Raphael, and Michael. And if another Messiah ever comes he will be in Shakespeare’s person.”

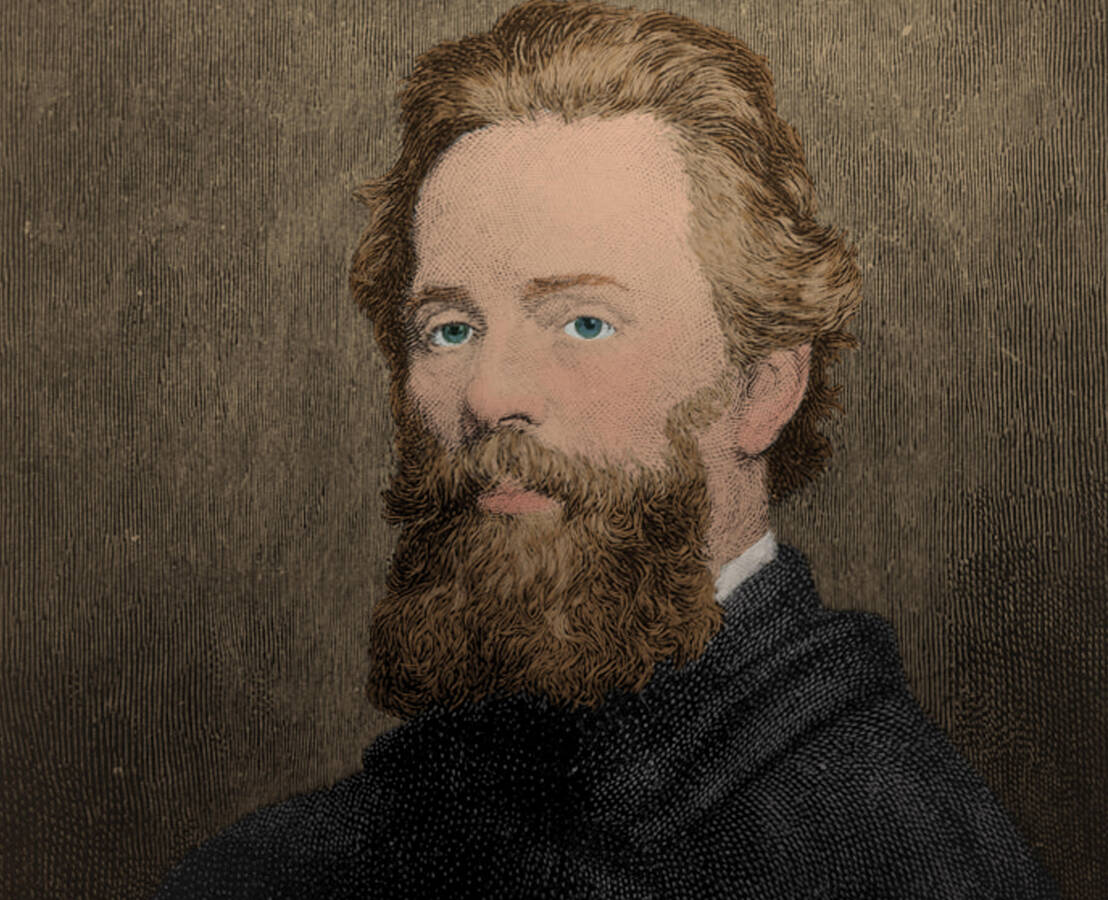

Melville, who was born 200 years ago this August, did not issue a formal declaration of his religious belief (or lack of it). But it seems fair to say that he was consumed with the foundational issue of humanity’s capacity for good or evil, and that this obsession sprang at least in part from his upbringing as the third of eight children raised by parents of Dutch extraction in New York, and in particular the influence of his pious but spendthrift merchant father, Allan, who died in distressed circumstances at the age of 49.

Melville, who was born 200 years ago this August, was consumed with the issue of humanity’s capacity for good or evil.

It perhaps says something for Melville’s philosophical balancing act that generations of scholars have claimed him both as the most scripturally minded of all American writers and as the most agnostic. His friend Nathaniel Hawthorne caught some of this duality of spirit when he wrote of him:

Melville can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other - If he were a religious man, he would be truly one of the most religious and reverential; he has a very high and noble nature, and better worth immortality than most of us.

There are no fewer than 650 references to biblical characters, places, events and books scattered through Melville’s 12 volumes of prose. Roughly two-thirds of them are to the Old Testament, 200 are to the New Testament, and the remainder are to the Apocrypha. These are not the statistics of a writer wholly indifferent to his relationship to his creator. It has been argued that Melville’s long-neglected, now ubiquitous Moby-Dick (1851) is one long biblical allegory, as well as a plea for religious tolerance. Ishmael, often regarded as the author’s voice, says he “cherishes every belief,” no matter how absurd or obscure, including ants who worship toadstools. He further insists that “good Presbyterian Christians” should not consider themselves superior to “pagans and what not,” and even proposes a sort of neo-hippie communality of existence: “The God absolute! The center and circumference of all democracy! His omnipotence, our divine equality!”

Creator and Creature

Clearly, though, Melville’s journey of faith amounts to more than merely a few generic observations on the human family, or greeting-card appeals for peace. Take, for instance, the penciled marginalia we find throughout his 1844 American Bible Society edition of the New Testament. When Melville read Paul’s counsel to the Romans, “Hast thou faith? Have it to thyself before God,” he annotated, “The only kind of faith—one’s own.” Melville further underlined the verses in which Christ instructs the multitude, “And call no man your father upon earth: for one is your father, which is in heaven,” and the verse in which Christ tells the disciples: “It is not ye that speak, but the spirit of your father which speaketh in you.” At the end of the book is the following rumination in Melville’s handwriting:

If we can conceive it possible that the creator of the world himself assumed the form of his creature, and lived in that manner for a time upon earth, this creature must seem to us of infinite perfection, because susceptible of such a combination with his maker. Hence, in our idea of man there can be no inconsistency with our idea of God; and if we often feel a certain disagreement from him or remoteness from him, it is but the more on that account our duty, not like advocates of the wicked Spirit, to keep our eyes continually on the nakedness and wickedness of our nature; but rather to seek out every property and beauty by which our pretension to a similarity with the Divinity may be made good.

Melville once suggested to Hawthorne the possibility that “God himself cannot explain His own secrets. Perhaps, after all, there is no secret. Yet all that makes us think there is remains, and must be spoken.” Melville added that he would stand with his friend as one in “the chain of God’s posts round the world” in their attempt to render artistically “the tragicalness of human thought in its own unbiased, native, and profounder workings.”

An Early Chronicler of Alienation

By the time he came to write his allegorical “Bartleby, the Scrivener” in 1853, Melville seemed to be principally concerned with humanity’s propensity for chosen isolation. Barriers of all sorts are pervasive in the story, which appropriately enough takes place on Wall Street. The titular character spends extended periods in “a dead-wall reverie.” He spurns conversation, declines the offer of hospitality and eventually dies confined in a jail cell. Could it be that Melville was exploring the theme of humanity’s proclivity for alienation fully a century before it was taken up by Samuel Beckett and his fellow school of theatrical nihilists.

Melville’s journey of faith amounts to more than merely a few generic observations on the human family, or greeting-card appeals for peace.

Biblical allusions are also strewn throughout the story. Tempted by the “old Adam of resentment,” the narrator recalls Jesus’ words, “A new commandment give I unto you, that ye love one another.” In its litany of human misery and perseverance—clearly, too, a throughline to Ahab’s stoicism in Moby-Dick—the story thematically reflects the strain of theodicy running through the Book of Job. Tellingly, in a reference to Job 3:14, Bartleby himself is said to sleep “with kings and counselors.” Perhaps, the tale’s narrator concludes, our ultimate purpose on earth is to endure the unendurable.

He remarks, “I slid into the persuasion that these troubles of mine touching the scrivener, had been all predestinated from eternity, and Bartleby was billeted upon me for some mysterious purpose of an all-wise Providence, which it was not for a mere mortal like me to fathom…. At last I see it, I feel it; I penetrate to the predestinated purpose of my life. I am content.”

By the time he came to “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” seemed to be principally concerned with humanity’s propensity for chosen isolation.

Melville went on from there to write “The Two Temples,” another opaque fable notable for its dreamlike monologues and allegorical density, and more specifically its disdain for the pretensions of those at worship in a fashionable New York church compared with the more convivial, secular communion among the audience of a London theater. The author comes about as close as he ever did to dropping his permanent mask of allusive irony and detachment when he writes at the conclusion of the story: “I went home to that lonely lodging, and slept not much that night, for thinking of the First Temple and the Second Temple; and how that, a stranger in a strange land, I found sterling charity in the one; and at home, in my own land, was thrust out from the other.”

Perhaps it is not entirely surprising that Charles Briggs, an editor at Putnam, turned down the story when Melville first submitted it to him, as “my experience compels me to be very cautious in offending the religious sensibilities of the public, and the moral of the ‘Two Temples’ would array us against the whole power of the pulpit.” This rebuff marks the starting point of a long and increasingly indigent second act to Melville’s once gainful literary career. “The Two Temples” was eventually published in 1924, 70 years after its original submission and 33 years after its author’s death.

The Devil Among Us

In 1857, Melville published The Confidence-Man, a nomadic farrago loosely in the tradition of The Canterbury Tales, in which the title character appears in numerous disguises, duping unwary passengers on a Mississippi steamboat. The overall theme, clearly, is trust. It is an odd book in many ways, one that never quite decides whether to go for straight slapstick and satire, or instead to examine its characters’ recurrent claims about human nature and the Christian obligation to do to others as you would have done in return.

More than a century after Melville wrote the novel, the last to be published in his lifetime, Peter Cook sat down to draft a film screenplay he called “Bedazzled”—“a low-budget retread of the Faust legend,” he disarmingly informed the press. Cook once admitted that his script “ripped off Melville” in dealing with an infernal bet on the fallibility of human nature. “I read that book, and I realized at once it was the most brilliantly metaphorical story about all these little barriers and pretensions of the virtuous middle-class being torn down by the devil among us,” he told me.

After that there remains only Melville’s extraordinary posthumous novella “Billy Budd, Sailor.” Critics have seen in the titular character everything from the personification of Melville’s masculine ideal to the perhaps inevitable interpretation (by the late Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick) of Budd as a latent homosexual and the story itself as a portrayal of homophobia. Leaving gender studies aside, the central point would seem to be that Budd accepts in true Christian humility the death sentence ultimately imposed on him by a drumhead court-martial convened by one Captain Edward “Starry” Vere. Following the verdict, Budd calmly lies down on the deck between two guns, apparently resigned to his fate. With his last breath he cries, “God bless Captain Vere.” Later in the story, Melville describes the death of Vere himself in a naval action against a French ship named The Atheist. Vere’s own last words are “Billy Budd, Billy Budd.”

Billy Budd’s physical flaws and moral inadequacies signify our fallen nature. No social theory can free man from his shortcomings, Melville reminds us.

We need look only at Melville’s protracted description of Budd’s execution to glimpse the intended symbolism. Suspended from a central wooden beam with his ship’s fore and aft masts set on either side, Budd departs the earth thus: “[T]he vapory fleece hanging low in the East was shot through with a soft glory as of the fleece of the Lamb of God seen in mystical vision and simultaneously therewith, watched by the wedged mass of upturned faces, Billy ascended; and ascending took the full rose of the dawn.”

Melville adds the detail that fragments from the beam from which Budd is hanged are subsequently treated as holy relics by his seafaring brethren. It is the ideal allegory, but for one telling fact. In giving Budd the significant physical defect of a stammer, Melville distinguishes between even the most God-fearing mortal and the deity himself. The stammer is a mark of humanity’s imperfection, and to further press the point, a valedictory ballad that closes the book refers to Budd’s relations with a certain Bristol Molly—unlikely, given the traditions of 18th-century nautical life, to have been wholly celibate. There may be a direct kinship between biblical justice and that of Captain Vere, but Billy Budd’s physical flaws and moral inadequacies again signify our fallen nature. No social theory can free man from his shortcomings, Melville reminds us, and nothing can avail against that hard truth.

Melville worked progressively from the inherited faith of his childhood to take what might be called a socialistic humanitarian view of the world. There are clearly ambiguities to be found in both his printed words and his private remarks. He mentions, for instance, humanity’s propensity to seek out “every property and beauty” binding mortals closer to God, while dwelling at equal length on our potential for depravity and evil. That same conflict might be glimpsed in any worthwhile literature, but it defines books such as Typee, Redburn and The Confidence-Man. As the author himself said when contemplating the immortal in art, “In this world of lies, Truth is forced to fly like a sacred white doe in the woodland; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself, as in Shakespeare and other masters of the great Art of Telling the Truth—even though it be covertly and by snatches.”

One might substitute “Melville” for “Shakespeare” to get the essential message: In a globalized yet increasingly bland and soulless world, we shall not taste the salty like of this quirky, elusive American original again.

"And I thank God for this; for all have doubts; many deny; but few along with them, have intuitions; Doubts of all things earthly, and intuitions of some things heavenly; this combination makes neither believer nor infidel, but makes a man who regards them both with equal eye."

- Ishmael ("God hears")

Ahab is a Quaker. A Quaker with a Vengeance! His name itself a doom and a negation. Like Richard Nix On.

I have just reread this article. Truly excellent.

I also believe Moby Dick is the greatest book ever written by an American. And thoroughly theological. Ishmael got his education on a whaling ship (not at Harvard or Yale) and also by voyaging in oceans and libraries.

Abraham Lincoln had less than one year of formal education.

Melville left school at age twelve (which I learned by reading David Markson's truly extraordinary This is Not a Novel and Other Novels.

They are our Great Ones. I hope and pray we can learn from them again in our time of national decline and despair.

Again, thanks for this essay. It's illuminating!

"I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb." - Herman Melville (in a letter to Hawthorne re: Moby Dick)

Said of Matt Damon's character in Good Will Hunting by his friends in the (Irish) neighborhood of Southie in Boston: my boy's wicked smaaat!

"I myself am a Savage, owning no allegiance but to the King of the Cannibals".

- Ishmael