Several months before the 2016 election, Harper’s Magazine published an unlikely essay by Alan Jacobs suggesting that in the midst of the fractious punditry gripping the country, we might benefit from the return of Christian public intellectuals. “Their task,” Jacobs suggested, “would be that of the interpreter, the bridge of cultural gaps; of the mediator, maybe even the reconciler.” Such thinkers existed half a century ago and occupied a prominent role in the public square, he wrote, but “they are gone now.”

It was a strange comment coming from Jacobs, who was, in a way, describing himself: a Christian intellectual who has dedicated most of his career to bridging gaps not only between Christians and non-Christians but also between disciplines and audiences.

Early in his career, Jacobs experienced what might be called an extended crisis of audience, a crisis he recalled when I interviewed him in February. At the time a professor of English at Wheaton College, an evangelical school outside of Chicago, he was publishing scholarly work within his field but was increasingly devoting time to writing essays and theological pieces for Christian magazines and journals. Switching back and forth could be disorienting, and he spent several years debating and praying about which audience he should focus on. “At one point, I just had an epiphany: You don’t get to choose.You’re gonna have to write for your scholarly peers, and you’re gonna have to write for your fellow Christians because you have things to say to both audiences. So, that means, you gotta learn to code switch.”

Since making that decision, Jacobs has published 15 books on literature, technology, theology and cognitive psychology and has written for such disparate publications as The American Scholar, First Things and Harper’s. His résumé is nine pages long without his book reviews (approximately 75) or online writing (hundreds of articles and blog posts). It calls to mind David Foster Wallace’s comment about John Updike: “Has the sonofabitch ever had one unpublished thought?”

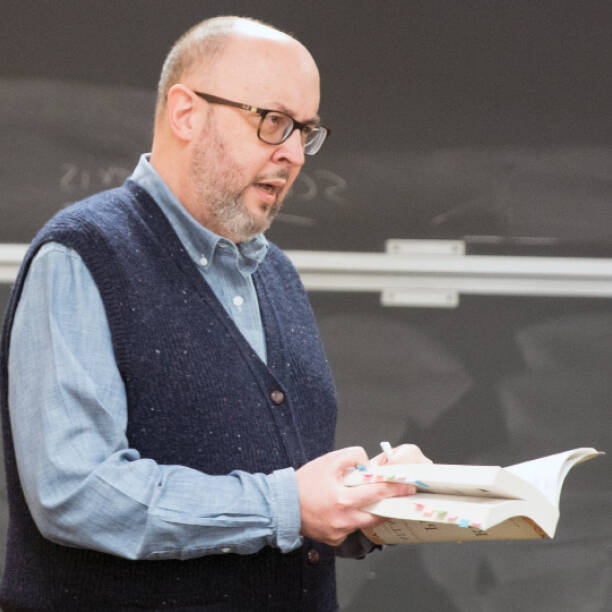

Alan Jacobs: "You’re gonna have to write for your scholarly peers, and you’re gonna have to write for your fellow Christians because you have things to say to both audiences."

Jacobs is now 59 and teaches humanities at Baylor University, a Baptist school in Waco, Tex., with the delightful motto “Pro Ecclesia, Pro Texana.” He has kind eyes beneath mantis-like glasses and a warm, mischievous smile framed by a trim salt-and-pepper beard. He looks and dresses less like an academic than a middle-aged middle manager at a tech company—which is to say, both cool and not.

In the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, Jacobs grew concerned over what he was witnessing. “I was watching the country come apart. I felt that, across the board, there was this failure to think. There was also a failure of charity, and I wanted to address that.”

So he quickly wrote How toThink: A Guide for the Perplexed, a short and engaging book that offers strategies for thinking more clearly and charitably at a time when the media fosters agitation and discourages thinking. The New York Times columnist David Brooks called it “absolutely splendid.”

More than a simple guide, it is an argument for learning to live charitably in the midst of diverse ideas and beliefs. Jacobs posed the book’s driving question to me: “If plurality is inevitable, are there ways to make that work for us without sacrificing what is distinctive to your own tradition and what you really believe in?” How to Think is written for a general audience, but this question is particularly pressing for Christians, who Jacobs thinks are becoming increasingly nasty and uncharitable while viewing that lack of charity as a sign of Christian strength.

Charity is a consistent theme in Jacobs’s work, a theme he derives from Matthew 22, where Jesus commands us to “Love your neighbor as yourself.” When I first met him 15 years ago at Wheaton (where I was his student), he had just published A Theology of Reading:The Hermeneutics of Love, in which Jacobs wrestles with what it means to read with caritas. As he wrote in another essay around that time, “The law of love, on which ‘all the law and the prophets’ depend, mandates charity towards one’s opponents in argument.”

In How to Think, one of the strategies Jacobs offers for thinking well is to belong to multiple communities, which can challenge your natural inclinations, and he draws on his own experience as an academic and a Christian to make the point. That he belongs to either community is something of a miracle.

Jacobs was born into a working-class family in Birmingham, Ala., what he calls “the urban South—the pit of the South.” He was raised, along with his younger sister, mostly by his grandmother. His father, a former Navy man, was a drinker with a mean streak who spent much of Alan’s childhood in prison. When he was not in prison, his father worked the late shift as a dispatcher for a trucking company, and when he lost that job, he became a bodyguard for a local builder with shady business practices, a job for which he qualified because he was not afraid to carry a gun and use it.

Jacobs describes his father as a man with a big personality who loved to pull out a wad of bills and pay for a meal; but it was Alan’s mother, who worked at a local bank, who was the breadwinner. One day, when Alan was still living at home, his father called from the Mississippi jail where he had landed after a drinking binge. Alan retrieved him, but not before his mother managed to remove his father’s name from all bank accounts and titles. For the rest of his life, his father was kept on an allowance.

One of the strategies Alan Jacobs offers for thinking well is to belong to multiple communities.

As I listened to Jacobs describe his childhood, I was reminded of something I heard Zadie Smith say to the Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard. Asking about Knausgaard’s father—who drank himself to death—Smith refered to Alice Miller’s The Drama of the Gifted Child and Miller’s claim that gifted children with unpredictable parents often develop a strong sense of adaptation to navigate their parents’ mood swings. With age, that ability turns into a profound sense of empathy. It is hard not to think that Jacobs’s emphasis on charity and his ability to “code switch” might stem from his own childhood.

Neither of his parents graduated from high school or saw any point in higher education, but the house was filled with an endless supply of cheap paperbacks that his family devoured in front of the television set, which was always on with the volume turned down. “When I close my eyes and try to remember the house I grew up in, what arises in my mind is an image of several people sitting on shabby old chairs and sofas in the salmon-pink living room, all absorbed in their books, with a cathode-ray tube in a wooden box humming and glowing from a corner,” he writes in Reverting to Type, an e-book that recounts his history as a reader.

When Jacobs was 3, his grandmother took him to the Pizitz department store in Birmingham, where he picked out The Golden Book of Astronomy. The store clerk demurred, saying the child was too young, but then his grandmother commanded Jacobs to read aloud from it. The clerk shut up and sold them the book.

Soon Jacobs was working his way through the pulps scattered about the house. He gravitated toward science fiction: At 6, his favorite writer was Robert Heinlein. He started school a year early and then skipped second grade.

His high school teachers did nothing to encourage his prodigious talents, nor did his parents. When, in his senior year, he told them he wanted to go to college, they were baffled. Unaware of student loans, he decided to attend the local school, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, to save money. The summer after he graduated from high school (at age 16), he got a job at a bookstore. He worked 24 hours a week and full-time during school breaks.

There, he fell under the influence of Michael Swindle, a colleague who brought Jacobs into his circle of friends, a group of “hipsters before there were hipsters,” who gave Jacobs an informal education in modern literature, music and art. In the days before the internet, it was the sort of intellectual and cultural playground that was only available in a city, even a small city like Birmingham.

Jacobs’s family was only nominally Christian, but when he was 12, he attended a Baptist revival where he “got saved.” A few weeks later, he was baptized and then almost immediately stopped going to church and claimed to be agnostic. That changed when, in college, he met Teri, an attractive, witty woman who happened to be a serious Christian. As he writes in Looking Before and After, his book on narrative theology, “I started reading the Bible and thinking Godly thoughts, because if I did, maybe, eventually, this remarkable young woman would allow me to kiss her.”

With Teri’s encouragement, Alan transferred to the University of Alabama, in Tuscaloosa, which had a stronger English department. A professor took note of his gifts and encouraged him to pursue graduate school. He applied to just one Ph.D. program, at the University of Virginia, and was accepted and moved to Charlottesville with Teri, his bride of two weeks.

Jacobs recounted this story over breakfast tacos at a joint called Torchy’s, our second meal there in as many days. He sounded less nostalgic than amazed. “Were it not for Teri,” he said, “I seriously think I’d still be in Birmingham managing a bookstore.”

When he was hired by Wheaton College at age 25, he had been a serious Christian for less than five years. “I was still a baby in a lot of ways” (not only in regard to faith; the custodians often mistook him for a student). He soon developed a rich collection of friends, and a few professors in the theology department—including the eminent church historian Mark Noll—took Jacobs under their wing, tutoring him in theology and church history.

In graduate school, Jacobs had seriously considered the Catholic Church, poring over Romano Guardini and John Henry Newman. “Newman was supposed to solve all my problems, and I think Newman made Catholicism permanently unattractive to me,” he said with a deep belly chuckle that somehow evinced his Alabama accent. When he and Teri moved to Wheaton, they visited a local Episcopal church and fell in love. “Being an Anglican is really the only way I know how to be a Christian,” he said.

Over the years, he has steeped himself in Anglicanism and has written a history of the Book of Common Prayer and served as his church’s liturgist. But being an Anglican in the United States has not been without tension. In 2004, in the wake of the consecration of the Rev. Eugene Robinson, the Episcopal Church’s first openly gay bishop, his parish split in two. Jacobs joined a group, including his priest, who left the Episcopal Church to form a new church that would eventually become part of the Anglican Church of North America. Since moving to Waco, his family has landed back at an Episcopalian Church, St. Alban’s, where the father of the film director Terrence Malick once served as choir director and where in the basement a picture can be seen of the reclusive Malick as a young chorister.

“It’s not easy, and it’s not fun,” Jacobs commented on being an Anglican in the United States. “But I have picked up from Anglicanism that kind of mediating and conciliating temperament and seeing if there is a way for people to live together in relative harmony even in significant disagreement.”

Writing, for Jacobs, is a form of thinking. When he begins to write, he does not like knowing where he is going but rather writes to sort through his ideas and questions. The essay is a natural form for him. “It’s a mimetic genre: That is, it imitates the flow of thought.” Jacobs had fallen in love with the form in high school when he discovered the essays of Loren Eiseley, but his early professional writing was academic. By the early 1990s, he wanted to write for a broader audience.

One day, at a bookstore in Chicago’s Hyde Park, he discovered a new journal called First Things. He submitted an essay on David Byrne of the band Talking Heads and the notion of “lifestyle” and, to his surprise, the journal published it. Soon he was a regular, writing essays in the tradition of C. S. Lewis and George Orwell, whom he calls “moral essayists”—writers with the power to face unpleasant facts. When Christianity Today launched Books & Culture, a broadsheet literary review, he began publishing there, too.

In his Harper’s essay, Jacobs notes the importance of place for thinking: “The question...for many Christian intellectuals today, is one of social and institutional location. From what place is one best suited to bear witness to what one believes to be core Christian truths, in a manner that is both free and audible?” Wheaton, which requires its faculty members to sign a statement of faith, has lately made national headlines for theological rigidity in dealing with faculty, but Jacobs credits the school with giving him intellectual freedom, and he turned down higher-paying job offers, staying at Wheaton for 29 years.

His explanation for why he stayed is succinct: “Would another school have given me a year off to explore what it means to read lovingly? I don’t think so.” He was also at the center of a group of friends, mostly Wheaton colleagues, who met every week and talked about their work and their ideas—thinking in community, as Jacobs refers to it in How to Think. But he and Teri were never completely at home in the Midwest, and they missed the South. When, in 2013, Baylor offered to make him a distinguished professor in their honors college and let him teach whatever he wanted, he accepted.

In his essays and books, Jacobs is something of a magpie, developing arguments and narratives by weaving in other writers and texts. His interlocutors and texts vary, but he invariably draws on W. H. Auden and C. S. Lewis, if they are not the outright subjects of his work.

A few years ago he noticed that Auden, Lewis and Jacques Maritain had given lectures on education within a few days of each other in 1941. It struck him as odd that in the midst of World War II, they were writing about education, and he decided to investigate. The result is The Year of Our Lord, 1943, which will be published this August. He expanded the story to include the poet T. S. Eliot and the French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil. They all harbored suspicion toward the liberal instrumentalism that had crept into education. They were worried that once the war was over, the resulting society would not be morally equipped to withstand future wars.

The book, whose form Jacobs modeled on Paul Elie’s The Life You Save May Be Your Own, tells a fascinating if sobering story. Despite the brilliance of the aforementioned authors’ writings and arguments, none of their prescriptions were implemented. They were a century too late, and “the reign of technocracy had become so complete that none can foresee the end of it while this world lasts.” Jacobs’s afterword is devoted to a sixth character, Jacques Ellul, who recognized the triumph of technocracy and hoped merely for a miracle to counteract it.

Jacobs wrote the book for more than one audience, though he told me that for those merely interested in the intellectual history of the 20th century, it might be a “fly caught in amber sort of story.” For Christians, it might serve as a cautionary tale. As Jacobs writes on the book’s final page:

If ever again there arises a body of thinkers eager to renew Christian humanism, they should take great pains to learn from those we have studied here: both what they agreed upon and what divided them. But may those future thinkers also be quickly alert to the signs of the times.

In his essays and books, Jacobs is something of a magpie, developing arguments and narratives by weaving in other writers and texts.

As he was writing the book, Jacobs published one of several pieces calling the smartphone an “idolorum fabricam, a perpetual idol-making factory.” He juxtaposed a passage from the sociologist Christian Smith’s work on “moralistic therapeutic deism,” in which Smith notes that for most American teens, God is primarily available as a solution of last resort, with a passage from Mircea Eliade’s The Sacred and the Profane, in which Eliade describes a similar phenomenon in ancient, primitive religions. Noting that our preference for idols (and thus religion as solutionism) is deeply ingrained, Jacobs says that modern technologies, which are solutionist in design, function as ready-made modern idols:

The primary goal of the makers of the idols, or New Gods (in their software and hardware avatars), is to ensure that we continue to turn to the idols for solutions to our problems, and never to suspect that there are problems they cannot solve—or, what would be far worse, that there are matters of value and meaning in human life that cannot be described in solutionist terms.

I read the post not long after finishing The Year of Our Lord, 1943 and thought of Jacobs’s admonition to be quickly alert to the signs of the times.

When I asked Rod Dreher, the conservative critic and author of The Benedict Option, why there are not more Christian intellectuals thinking deeply and seriously about technology the way Jacobs is, he responded dryly:

Because it’s really hard. Though we may be morally and theologically oriented toward tradition, we, like most Americans, are total suckers for technology. Alan understands that technology is, more deeply, a way of construing reality. This is an alien thought to Americans who are neither Amish nor Wendell Berry.

Jacobs began thinking more seriously about technology in the late 1990s, when he taught himself to code. At that time the internet was emerging as a vibrant place for intellectual conversation, and he became an early and active participant. As Alexis Madrigal, Jacob’s technology editor at The Atlantic, told me, “This was a different era of Twitter, and of writing on the internet as a whole. There was more mixing of genres and types of writers.” In many ways, it was a medium perfectly suited for Jacobs, who at the invitation of Ross Douthat started contributing to a blog called The American Scene.

By the end of that decade, Jacobs noticed he was losing his ability to focus on books for extended periods of time. Worried that it might never return, he made strenuous efforts to reclaim his attention and made adjustments to his online habits. He also started to work out ideas around concentration, reading and technology on a new technology blog called Text Patterns. He collected these ideas in Reading in the Age of Distraction, which argued for the value of “whim” in reading and made recommendations for preserving the pleasure of reading amid the noise of the internet.

He published the book in 2011, and that year Madrigal hired him as a tech correspondent for The Atlantic. When I asked Madrigal why he recruited an English professor from a Christian college, he replied: “Alan was one of, if not the, most interesting and heterodox thinkers. He approached these topics with a seriousness that most people didn’t back then, and he could bring a whole set of analytical tools to bear on social media that others could not. I saw his Christianity as a bonus feature of his profile, which might yield unconventional observations and insights.”

In How to Think, Jacobs encourages readers to take five minutes to absorb a claim before launching into “refutation mode.” It is a strategy he learned the hard way on Twitter, as he writes in the introduction: “Many are the tweets I wish I could take back; indeed many are the tweets I have actually deleted, though not before they did damage either to someone else’s feelings or to my reputation for calm good sense.” As a mutual acquaintance told me, “For someone who writes so much about the importance of charity, he is not very charitable online.”

When I asked him about this, he responded candidly: “The platform encourages intemperate, rigid, narrow, simplistic emotional responses, and when I’m on that platform, I’m vulnerable to those things. And it’s embarrassing at my age and to have been a Christian as long as I have been a Christian not to be able to do better.” He has slowly scaled back his Twitter usage and told me that for the past few years, he has prayed for discernment about when to be silent. “There’s so many people who will have something to say about the controversy du jour,” he said. “Why do I need to be that guy?”

But when I asked Madrigal about Jacobs, he called him “a deep, generous thinker. If you made a spectrum of analysis and put ‘hot take’ on one side, Alan Jacobs would be at the opposite pole.” Indeed, a number of people I spoke with referred to his generous spirit. I know of several young writers and academics whom Jacobs has befriended or mentored. Some of those are former students, myself included, while others are merely Christian writers who have felt alone and have written to him, looking for advice or counsel.

Jacobs will turn 60 in September, but he seems to be the rare person who is accelerating with age. Several times he mentioned his desire to be more ambitious and cut new paths, and he tinkers with his writing and reading habits the way other people his age tinker with vitamin supplements and low-cholesterol diets.

In a post in late 2015, he wrote about curbing the distractions of the internet. He had deleted his Tumblr and Instagram accounts and had returned to older technologies: paper, CDs and even a “dumb phone”—though he had returned to his iPhone when I visited him.

Lately, he has started taking notes on multicolored index cards. He spends less time writing on a computer and more time writing in a notebook, using a practice called bullet journaling. He jots ideas down as they come to him, and reads over the notes when he has time. “It’s always like putting stuff in the compost pile and stirring it around and then putting more stuff in the compost pile and stirring it around. And then I take it out and move it to the place where something needs to grow.”

If an idea is still gnawing at him, he will work the idea into a more developed sketch. When he gets on a roll, he grabs his computer, sometimes writing four or five thousand words at a time. “That doesn’t mean that they’re necessarily going to be good words,” he told me. “But it’s this kind of desperate let me get it all out while I still can.” When I visited him, he was in the midst of six different essays and a new book.

He calls his new book a theological anthropology for the Anthropocene Age, an account of what it means to be human in an era that seems radically empowering but also leaves the individual feeling helpless before technocratic powers. Theologians have not risen to the task, but Jacobs thinks that novelists like Thomas Pynchon can offer clarity.

“I have lots of ideas,” he told me shortly before I left. “I always have more ideas than I can possibly write about.” So he prays for discernment about what ideas to pursue and what ideas to let die. “And increasingly, over the last three or four years, I pray more and more that God would teach me when it’s time to shut up. That’s the thing that I’m least good at. Just shutting up.”

'In his own lifetime, the example of [Newman's] singular piety and integrity was widely esteemed throughout England by both Catholics and Anglicans alike....[Conscience] inevitably led him to obedience to the authority of the Church, first in the Anglican Communion, and later as a Catholic.' Saint Pope John Paul II

https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/speeches/1990/april/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19900427_card-newman.html

Greg Herr

Blessed John Henry Newman Catholic Church ('Anglican Ordinariate')

Hehe we now finally live at the End because everyone knows or not a (absolute) truth contrary to past generations; social media are a great toll to transmit swiftly this truth(s) or lie(s) and a new man in Christ knows it.