The top of the wikuom is just visible from the retirement residence of the Sisters of Charity. Its off-white canvas approximates the birch bark the Mi’kmaq people used to construct their homes when they ranged across what are now the Maritime Provinces of eastern Canada. Pine poles hold the structure up and leave an opening to release smoke from ceremonial fires. Inside the wikuom (the Mi’kmaq word for what you may have known as “wigwam”), Catherine Martin, a filmmaker and Mi’kmaw activist, leads ritual prayers, burning sage and sweetgrass, cedar and tobacco, and teaching visitors about her people’s way.

The wikuom is not a relic of the past. It is an invocation of a future in which First Nations are respected as equals in Canada.

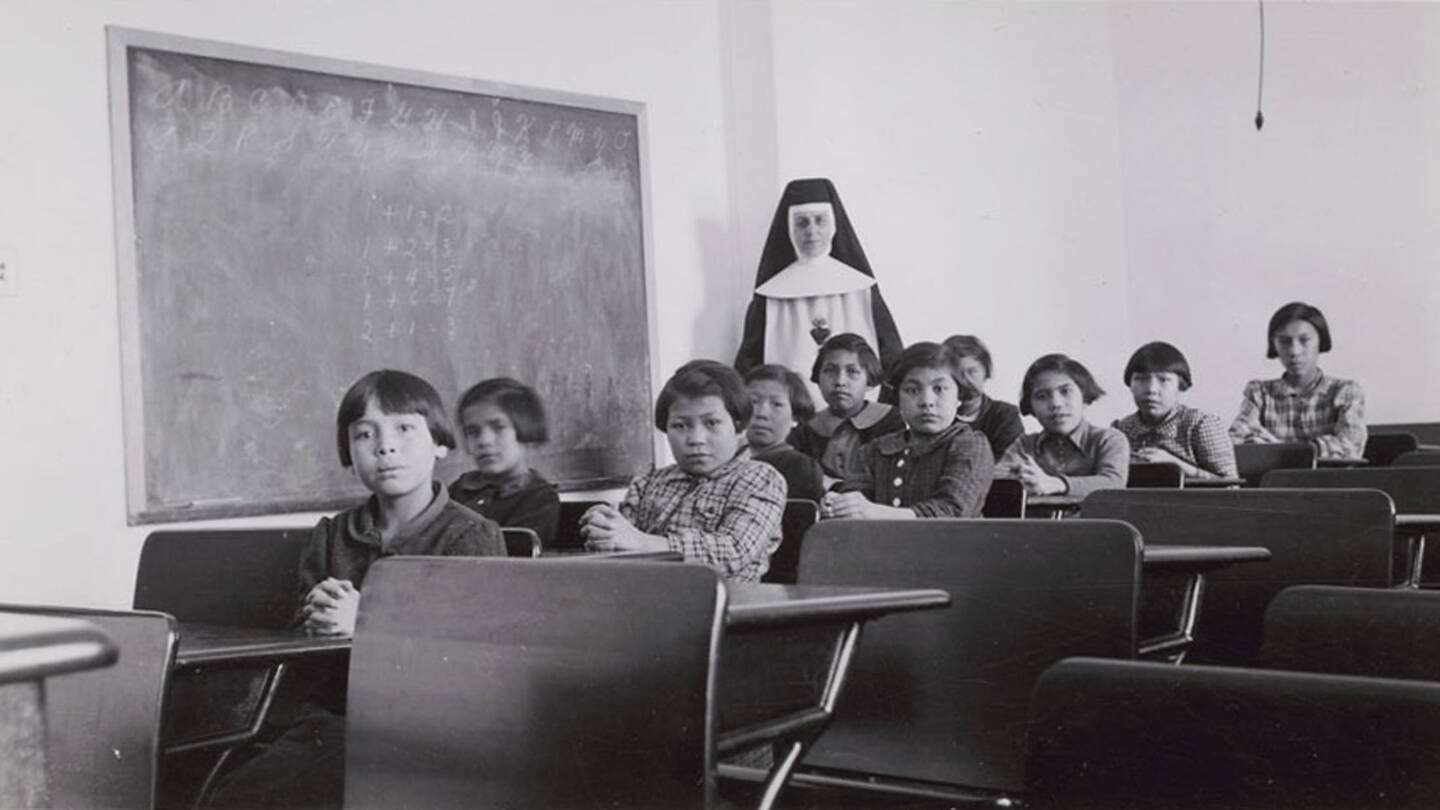

Last spring, when the wikuom was erected at the University of Mount St. Vincent, Ms. Martin held a visiting chair in the women’s studies department at the school, founded by the Sisters of Charity in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1873. The prayers she offered were for the victims and survivors of Canada’s centuries-long drive to eradicate its native peoples—in particular, the Mi’kmaq children forcibly taken from their families on reserves and sent to the government-sponsored boarding school the Sisters of Charity staffed for close to four decades. Former students of the Shubenacadie Residential School tell of being beaten, physically scarred for speaking their native language, forbidden from communicating with siblings, humiliated for wetting the bed and whipped with leather cat tails if they attempted to escape.

As the nation has embarked on a process of truth-seeking and reconciliation to confront the crimes of the residential school system and the racism behind it, religious orders, churches and other nonindigenous Canadians have had to face their culpability. Even after it signed the United Nations Declaration of Universal Human Rights in response to the horrors of World War II, Canada wrenched children from their mothers and sent them to be stripped of their culture at schools administered by Christian churches. The sisters whose order staffed the Shubenacadie school and another in British Columbia are among the groups confronting this history and trying to imagine what reconciliation means. They are learning that to write a better future, they have to edit their understanding of the past. “To learn that it was racist, that it wasn’t helping—it was very hard for some of our sisters,” says Sister Donna Geernaert, president of the order when the reconciliation process began. “So part of what I’m trying to do is make sense of the past and face it.”

“To learn that [the school] was racist, that it wasn’t helping—it was very hard for some of our sisters.”

It is such a Christian word: reconciliation. Can a private sacrament, a movement between soul and God, be adapted to heal a division in the polis? How does a religious community embark on a spiritual endeavor with people they have harmed? These are questions Sister Joan O’Keefe, current president of the Sisters of Charity of Halifax, is puzzling over.

“My goal is to continue to build those relationships and to respond to the invitation to be part of the process,” Sister O’Keefe says. “We colluded in a racist system,” she says of her order’s role in running the residential schools. “It’s not enough to ask for forgiveness. The point is to listen to their stories…. You can’t reconcile if you don’t know the truth.”

A Long Legacy, a Long Reckoning

The schools were not part of an education program, the First Nation peoples argue and the Canadian government admits. They were part of an elimination plan. In 2008, then-prime minister Stephen Harper issued an official apology for the schools and decried the racist assumptions behind them. “Two primary objectives of the residential schools system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives were based on the assumption aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal,” he said, speaking from the floor of Parliament in Ottawa.

The reckoning was sparked in the 1990s, when Phil Fontaine, then head of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, revealed that he had been physically and sexually abused while a student at a residential school run by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, an order of priests and brothers. Then came a series of books and an outpouring of allegations all over the country. In the early 2000s, leaders of several congregations of women religious met to talk about developing a coordinated response to the threats of lawsuits.

The schools were not part of an education program, the First Nation peoples argue and the Canadian government admits. They were part of an elimination plan.

“There was a sense from the women religious: ‘Let’s get the legal issue out of the way because the real work is reconciliation and healing,’” Sister Geernaert recalls. The Sisters of Charity were never named in any litigation, but they had retained lawyers when former students leveled accusations.

Meanwhile, the federal government was moving in the same direction. In 2005 it consolidated all the lawsuits against the government and church groups and agreed to an omnibus settlement that established a restitution fund for victims of the residential schools. The government and church entities paid into the fund on the premise that they would be indemnified against future lawsuits.

By 2017 that fund had paid out $3.1 billion to more than 37,000 victims of the residential schools: a base sum of $10,000 each, plus more depending on how severely they were abused and how grievously their lives had been affected later on. The Sisters of Charity contributed $250,000 to the fund and continue to give to indigenous groups. They also paid for a delegation of First Nations people to meet with Pope Benedict XVI in Rome in 2009 and contributed to a fund to build a memorial on the site of their former school.

An arguably more difficult condition of the legal settlement has nothing to do with money and everything to do with memory. It required the Canadian government to establish a truth and reconciliation commission, which published testimony from residential school survivors in 2015. Nonindigenous Canadians would have to hear what happened, rearrange their ideas about their past and commit to building a different future.

Canada is not the first society to attempt such a social reconciliation. Beginning with Chile in 1990, when a commission set out to establish a true account of human rights violations committed by the government of Augusto Pinochet, several nations overcoming violence or war have embarked on such processes. In South Africa, Rwanda, Uganda, El Salvador and elsewhere, truth and reconciliation commissions have met with varying degrees of success. They are charged with addressing specific harms, but they also consider larger, historical injuries. So Truth and Reconciliation Canada specifically addresses the residential school system, but it exists in the context of 500 years of dispossession and violence against indigenous Canadians.

“The work and the time that is required for healing...will take the rest of the lives of those who were abused and those who abused and the rest of the lives of the people who inherited the aftereffects,” says Catherine Martin, the Mi’kmaw woman who erected the wikwuom.

Truth-telling about the residential schools in Canada is an essential element, even if some would rather rush toward forgiveness.

The social reconciliation process involves several steps, explains Robert Schreiter, a professor of systematic theology at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago and a member of the Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, who has worked and written extensively on the truth and reconciliation initiatives in South Africa and Rwanda. It is not linear, but it has standard elements, he explains: the healing of memory, truth-telling, restitution and forgiveness.

“What we’re trying to do in a social reconciliation is not change the past but change our relationship with the past,” he explains. “In a sense it reverses time.”

As long as the injury and injustice of the residential schools were unacknowledged by nonindigenous Canadians, Father Schreiter says, their memory and impact continued to tear at survivors and their descendents. For reconciliation to work, members of perpetrator groups need to acknowledge what happened, put in place protections to ensure it does not happen again and make amends. Truth-telling is an essential element, Father Schreiter says, even if some would rather rush toward forgiveness.

The power in reconciliation lies with the victim, says Michel Andraos, another member of the faculty at Catholic Theological Union and a Canadian citizen who has written about reconciliation rituals, but people of the perpetrator groups have an important role to play as well.

“To make reconciliation happen, they need to acknowledge the violence of the past and restitute deeply, at some cost,” he says. “It’s a long-term process,” but one pregnant with promise. In the sincere reconciliation encounters between First Nations people and nonindigenous Canadians, he says, “there is a way forward.”

But like the sacrament in the confessional, social reconciliation requires both an examination of conscience and a heartfelt repentance. Mr. Andraos suspects the hardest aspect for Christians and Catholics to accept might be the idea that their religion was not incidental to the violence but was central to it. “It was actually the theology that was violent,” Father Schreiter says. “We need to look at the theology that blinded us and prevented us from seeing.” The root sin in the case of the residential schools, he says, was the lie that European and Christian culture was superior to First Nations’ cultures.

That lie made everything else possible.

‘Kill the Indian in the Child’

Part of the challenge of reconciliation is that it requires the perpetrator to reckon with evil. It is frightening to look at the church’s role in the schools and admit nuns chose to harm children. It is tempting to brush it away, to urge a hasty forgetting.

Sister Donna Geernaert, former chancellor of the University of Mount St. Vincent and past president of the Sisters of Charity of Halifax, knew her order taught at the Shubenacadie residential school until it closed in 1967, but it had never been part of her work. She took her final vows after it closed and worked in academia and administration, served on committees of Canadian churches engaged in justice work (including some for First Nations’ rights) and advised the conference of Canadian bishops on ecumenical dialogue. If she thought of the Shubenacadie school at all, it was as a place older sisters had offered pious service, ministering to First Nations children who were poor and in need of an education.

As the sisters followed the dictates of the Second Vatican Council to move out of institutions and into community work, Sister Geernaert thought, they left the school behind, along with their veils and black gowns. Yes, the sisters had used discipline and teaching methods no one would use today, and there was a focus on assimilating the children into white society that did not match current ideas on respect for cultural differences. But the school was a part of its time, she thought, and part of the legacy of the sisters’ charitable deeds in Canada.

That is not how First Nations people remember the Shubenacadie school, or scores of others like it. For one thing, they refer to themselves as survivors, not students or alumni. When the Canadian government convened a series of public hearings on the schools in 2011, part of the omnibus settlement that resolved hundreds of abuse lawsuits, Sister Geernaert listened for hours to the testimony of Shubenacadie survivors. She still remembers the bodily sensation of being at a hearing. It was as though the pain the people were recounting, the pain that followed them and devastated their families, was transferred to her.

Hour after hour the Shubenacadie survivors spoke. Men and women told of how they had been forced onto trains or pushed onto buses by the federal employees who oversaw indigenous reserves—or how their parents had sent them willingly, thinking they would gain advantages they could not have on impoverished reserves. The survivors testified about being beaten, starved and locked up in cabinets if they were caught sneaking into the girls’ dormitory, homesick and lonesome, to see a big sister. They recalled constant hunger and fear. Some were called only by numbers and forgot their names. Instead of receiving an education, they were forced to work in kitchens and laundries and at farm labor; if they attempted to escape, they were whipped until their backs were bloody and scarred. The Royal Mounted Canadian Police chased them down, but the school principal administered the beatings. Hospital records suggest two children at Shubenacadie died from injuries they sustained in beatings. The men told of being 5 or 6 years old and jeered at for wetting their beds, forced to carry their urine-soaked sheets on their heads through the dining room, their bare bottoms exposed in hospital gowns. There was sexual abuse.

The survivors testified about being beaten, starved and locked up in cabinets if they were caught sneaking into the girls’ dormitory, homesick and lonesome, to see a big sister.

These are claims that Truth and Reconciliation Canada, a government entity, has verified, determined true and paid damages for. The brutality and lovelessness of the treatment call to mind a notorious psychological experiment conducted at Stanford University in the 1970s in which college students played the role of prisoners and prison guards. The experiment had to be called off because the students playing the guards grew so brutal and sadistic.

The schools never had enough food, and the buildings were of shoddy construction, subject to mold and damp. Death rates from infection and injury at the residential schools far outpaced the rest of Canadian society, according to the journalist Chris Benjamin in his book Indian School Road: Legacies of the Shubenacadie Residential School. Some children died trying to find their way home to heartbroken and shamefaced parents, who must have thought, “How did I let my child into this horror?” Other times parents showed up at the schools seeking to see their children and were denied—and the homesick children were never told their parents had asked for them.

The national policy was explicit: The children needed to be taken out of their communities and away from their families to “kill the Indian in the child.” All students, whether they had family or not, were legal wards of school principals. When they were released as teenagers they returned to native communities broken, estranged from family, unable to speak their language but barely educated in English. Addiction and domestic violence roared out of them. They flooded through generations and out through families and washed back up in more ruined lives.

When they were released as teenagers they returned to native communities broken, estranged from family, unable to speak their language but barely educated in English.

“To sit in the room with people telling their stories of how they were abused, you feel that in your stomach. You can’t not be affected by other people’s pain,” Sister Geernaert says, recalling the testimonies. Her order did this, she realized—her good order of loving and brave women, the ones smiling in those pictures in the archives, those sisters who set out from the parishes of Halifax to build the church in Canada, to bring the faith to God’s people. They rent this hole in the universe that the Mi’kmaq are are still falling through.

“You don’t want to think that your congregation did things that hurt other people. But it’s important to hear it, and it’s important for people who haven’t been heard to speak,” Sister Geernaert says.

Facing—and Reclaiming—a Heritage

Sitting still with open ears is no small thing. First Nations people began complaining about the residential school system as early as 1879, but they were ignored. The white Canadian government and its Christian allies thought they knew better than the indigenous parents begging for their children.

“We were co-opted into a system that was racist, but we didn’t see it at the time,” Sister Geernaert says. “We see that we have an inheritance of hurt and injury that has harmed others and for that we are sorry.” She wants to believe that individual members of the Sisters of Charity did not knowingly commit abuse, but she knows what happened at Shubenacadie is part of her inheritance. “It’s a heritage of guilt, if you like.“

Rebecca Thomas, a Mi’kmaw woman and the student services advisor to First Nations students at Nova Scotia Community College, is one of the people who inherited the damage of Shubenacadie. Her father was there for two years in the 1940s, taken with several siblings when he was 5 years old. He was not permitted to speak to his siblings and was punished when he tried. For him, Shubanacadie was a place of loneliness and fear, persistent physical abuse and a cold hunger. He recalled that when he uttered his Mi’kmaw language as a little boy, he was cut with scalpels; his shoulders still bear the scars. When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission held hearings in Ottawa, he went and listened, but he did not speak. It took him more than a year to deposit his restitution check from the settlement fund, he told his daughter, explaining, “Taking that check seemed like I was absolving Canada of what it did to me.“

An aunt helped get him out of the school and into upstate New York, but then he was a lost child in the United States, in the foster care system and in reform school, on the street and in trouble, with demons that hounded him through adulthood. Ms. Thomas was raised by her white mother—her father lost to addiction, an intermittent and unsteady presence in her life. He stopped drinking 17 years ago and has since built a strong relationship with Ms. Thomas, rediscovering his Mi’kmaw culture and fostering the same in his daughter as he recovers.

Still, Ms. Thomas feels she inherited an absence. “They took away my language, my culture,” she says, thinking about the rupture that occurred when her father was removed from his home and community. For Ms. Thomas, who is a poet, the loss of language cuts particularly deep. She knows that a language holds within it a way of seeing the world, a bridge for understanding and making sense. As she rebuilds a Mi’kmaw sense of herself, she knows there will always be gaps: “I would be a fluent Mi’kmaw speaker if it weren’t for the [Shubanacadie] school. There are always going to be bricks missing from that bridge.”

Ms. Thomas sees reconciliation moving in several spheres at once: within families over broken relationships, such as the one she experienced with her father; within First Nations, as she is discovering when she reclaims a Mi’kmaw vocabulary; and across Canadian society, as the nonindigenous face history. But she is not rushing to forgive anyone prematurely. “I think in order to have a good and meaningful reconciliation, we need to sit with the truth for a while,” she says.

Making Amends

Ms. Thomas’s father has managed to outrun his demons, but hundreds of others have not, says Patrick Small Legs-Nagge, a social worker and member of the Piikani First Nation in Alberta.

“The thing that happened with these kids is there was no way to process what happened to them,” he says. Psychological counseling sessions for residential school survivors, another component of the joint settlement, just reached the final group of survivors last year. “For some the counseling is helpful, transformative,” he says. “Some will never be able to change; the damage is too great. They’ll take everything with them to their death.”

Mr. Small Legs-Nagge thinks the University of Mount St. Vincent, as another learning institution associated with the Sisters of Charity, is making progress. He credits university president Mary Bluechardt with taking the implications of reconciliation seriously. Last year Mr. Small Legs-Nagge assumed a new post, special advisor to the university president on aboriginal affairs.

The university has an aboriginal student center that serves more than 150 indigenous students at the university. It conducted a post-secondary education needs assessment with Mi’kmaq communities in the Maritime provinces in 2014, and it flies the Mi’kmaq flag alongside the flags of Canada and Nova Scotia. The university hired its first indigenous professor last year, Sherry Pictou, a former chief of the L’sitkuk First Nation.

Last fall the school hosted an art installation-like memorial—a haunting exhibit of thousands of embroidered moccasin tops, each donated by the family of a missing or murdered indigenous woman. The event brought Mi’kmaw and other First Nations people to campus, where they performed prayers and remembered their daughters. Mr. Small Leg-Nagge says there is still more work to do, particularly to convince European Canadians that building a right relationship with First Nations societies is a matter of concern for them. “This isn’t just the work of indigenous or even primarily the work of indigenous. It’s on the settlers,” he says. But he has hope: “A lot of good can come from all the work the Mount is doing.”

Gerry Lancaster, another Sister of Charity, speaks with gentleness, nearly whispering into the phone. For 25 years she has been part of Kairos, an ecumenical community working for racial justice in Canada and frequently advocating for First Nations around fishing rights and borders. The horrors at the residential schools shocked her. It was destabilizing to think of her good sisters being so inhuman, she says. How did it come to that, the cooperation with evil?

When she was asked to represent the Sisters of Charity at a planning meeting for the Truth and Reconciliation hearing in Halifax in 2011, she was frightened. “I was afraid to walk in the door. But you can get through it,” she says. “A question came to all the church people at the planning event: ‘What are you doing in terms of reconciliation?’ I stood up and said, ‘I...I am a Sister of Charity. We ran the residential school. I sincerely apologize. What we are doing now is our own inner work,” she said. The sisters need to turn their attention to their own transformation, she said.

While the government implements the long list of recommendations from Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports, and while First Nations people like Catherine Martin and Rebecca Thomas try to untangle the past from the present, the sisters need to examine themselves and track a new direction, Sister Geernaert says. “First of all, we have to get over the denial. Then acknowledge the wrong having been done and that it affects generations—and that we are all human. And the First Nations people are trying to reclaim their dignity. We have to see all of that with a large heart,” she says. “The hardest thing is facing the fact that we were responsible for so many people, for robbing them of their dignity and their culture. How can we now repair the damage and do our part?”

She speaks slowly, groping through the shadowed past, struggling to look at it squarely. “To cut their hair. To put them in a uniform. To separate them from their loved ones. To have no one to love them.” Her voice clouds with tears.

“The hardest thing is facing the fact that we were responsible for so many people, for robbing them of their dignity and their culture.

“We need reconciliation to gently put a salve on the wound and we need to do the heart work, helping people in terms of their recovery, to be supportive of their resilience,” she says. Sister Lancaster says she wishes that everyone in her community—and European Canadians more generally—could share the encounters she has experienced in the indigenous healing rituals. United in their frailty, the victim and the perpetrator, the wounded and the inheritor of the guilt—both sides are finally human.

Sister Lancaster and another sister go to pow wows in the summer, just to be present, to be a Sister of Charity respecting Mi’kmaw culture. She participates in workshops that aim to educate European Canadians. And she takes part in healing rituals, praying as an indigenous elder burns sage and listening as young people tell their parents’ stories, hoping to release them. She sits with elders, washes the smoke of sage and cedar over her as a Mi’kmaw elder burns the plants in a cleansing ceremony called smudging. The smoke rises to the sky, taking the hurt, the shame, the horror with it. At least that is the hope.

In 1948 the Government of Canada enacted a law which required the written permission of a parent of any child going to a residential school. Thus, after this date parents were well aware of where their children were going.

And your point is??? You apparently assume there was free choice by parents to knowingly have their children abused and their spirits broken. They may have known where they were physically, but not what they actually endured. The power differential between parents and religious was enormous. The poverty of families was probably such that hunger and disease with no educational opportunities at home persuaded parents that the "good sisters" were a more promising option. I find your inferences troubling and unacceptable. Indigenous children deserved decent loving care and education, not the hell holes they encountered, no matter what legalese documents their confused or intimidated parents may have signed.

I was about to post a similar reply but yours is better, no doubt strengthened by your own experience in an institutionalized environment. Bottom line, you don't take children away from parents except in the most dire of circumstances, in spite of any legalistic window dressing. And the comment at the top of the thread is an exercise in blaming the already victimized and compounding their victimization.

What a thoroughly sad story! What is destroyed cannot always be rebuilt, especially cultures.

I had the great misfortune to attend a boarding school in Wellesley Hills, MA run by the Halifax Sisters of Charity for my first five years of schooling. While certainly nothing approaching the cruelty of the institutions in Canada, it was an abusive environment emotionally, spiritually and physically. And this was an expensive private school. It was a brittle, cold, strict atmosphere despite the impeccable appearance. I ran away at 10 years old, and prayed I would be expelled. No such luck. At least the sister superior listens to the victims and contributes to reparations, unlike the self-excusing religious orders in Ireland.

Probably the most significant comment in this article was "We need to look at the theology that blinded us." Both church and civil leaders thought they were doing the right thing in (biblically: make disciples of all nations) making Christians and (civilly: "westernizing" the native peoples not only of this continent but throughout the colonial world). As to the physical discipline, the separating of male/female siblings, and the insistence on the use of the culture's dominant language, that wasn't limited to the schools for Native children, as may who attended boarding schools in the early 1900s would attest to. Even in our local parochial school in the 1950s that wasn't uncommon. Granted, a few people horribly abused their position through abuse—physical, sexual, and emotional—and for that apology and reparation needs to be made, but the majority who served in these schools tried to do the right thing and thought they were serving God. But back to the theological question: it's a good reminder that our understanding needs to change. Some day soon maybe we'll also realize that the current theology in various other areas such as homosexuality. Still, to judge people who act in good faith by the standards of their era by the values of a later one is also unjust.

Thank you for publishing this article. I hope that a series of other articles will follow, at least one on the "Indian Boarding Schools" in the U.S., and another on atrocities done to the indigenous peoples of California in the "CA Mission Era". In general, Americans were not educated in school, to these historical, often genocidal, incidents and situations visited upon the indigenous population by ancestral colonizers, settlers, and churches.