The turn of the 20th century for the Catholic Church in Great Britain might be called the age of the “celebrity convert,” a time when prominent Protestant and atheist writers “swam the Tiber” to become Catholic. Following in the footsteps of the earlier Oxford Movement and 19th-century figures like Cardinal John Henry Newman, their ranks included G. K. Chesterton, Ronald Knox, Herbert Thurston, S.J., and Robert Hugh Benson (whose apocalyptic novel The Lord of the World has been repeatedly cited by Pope Francis as a fave); they would be followed in later years by famous names like Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Christopher Dawson, Edith Sitwell, the actor Alec Guinness and Scottish writers like Muriel Spark and Compton Mackenzie.

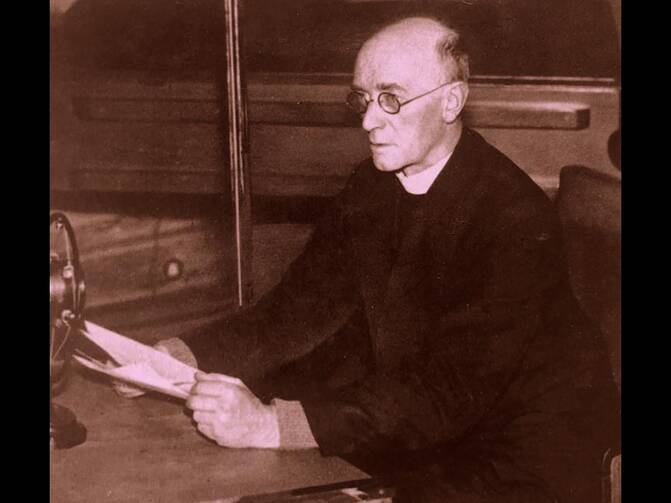

There’s another name that belongs to that list that would have been familiar to most if not all of the names above: C. C. Martindale, S.J.

If you’ve never heard of him, read these lines from a 1963 obituary in America: “It is presumptuous to assess any man’s ultimate importance. It lies hidden with God,” wrote the editor of the renowned Dominican journal Blackfriars, Illtud Evans, O.P. “But no one who considers the history of the Catholic Church in England during the last fifty years can ignore the decisive part that Fr. Martindale played in the evolution of an adult response to the demands of our time.”

Cyril Charlie Martindale (don’t ask me why it’s Charlie and not Charles, I don’t claim to understand the British) was born in 1879 in London. Raised Anglican, he entered the Catholic Church as a teenager under the guidance of Jesuit priests; he then joined the Society of Jesus at the age of 18, starting in the British novitiate in Roehampton but soon moving to Aix-en-Provence, France, in an effort to improve his health.

Martindale would suffer from poor health throughout his life: “He was never well,” Father Evans wrote, “and as the years passed, the routine of pain, recovery and relapse—no one knew more about hospitals than he—became habitual.” In a 1967 biography of Martindale, another famous British Jesuit writer, Philip Caraman, S.J. (the book is dedicated to Evelyn Waugh and his wife Laura), wrote the following about one health scare:

Although the simple French cuisine suited him, the doctor decided that he needed English food, and prescribed raw beef, which he took in the form of dark violet tablets; and then tea, or rather a sweet ink-coloured fluid. He became extremely weak, and then was placed in the infirmary where he could take only hot milk. He perspired four or five times a day. It was even thought he might die.

(I can’t help but note: If perspiring four or five times a day is a death sentence, I’m done for.)

Martindale proved a wunderkind with languages during his Jesuit formation, which included several years studying philosophy at Oxford, Stonyhurst and Roehampton in Great Britain (and teaching stints at both) and theological studies at St. Beuno’s in Wales. He was ordained in 1911, then returned to Oxford for further academic work and a teaching position in the humanities.

Despite what seemed like a sure future as a professor, Martindale would find his Jesuit life defined by his work as an apologist, preacher, biographer and spiritual writer. The closest analogy to an American figure might be Archbishop Fulton Sheen. “No one would have guessed in 1905 that the classical scholar whose Oxford career was a unique litany of academic achievement would in after years spend little time in formal teaching, would write no works of erudition,” wrote Father Evans. “And yet the resources of an exact scholarship were always there. He could afford to popularize, to write much that seemed slight or even improvised, because beneath it all there was the firmest of foundations.”

His academic work included supervising a translation of the Bible from Latin and many hours teaching Greek and Latin in the classroom. He also wrote biographies of Bernard Vaughan, Charles Plater and the aforementioned Robert Hugh Benson, catechetical texts, popular novels, Scripture commentaries, hagiographies and, later, books on Fatima.

In 1927, he showed up in The New York Times when the Duke of Marlborough became Catholic: Martindale presided at the ceremony. It was no anomaly—Martindale (or his colleague Martin D’Arcy, S.J., or his biographer Father Caraman) cropped up in countless such stories of Brits entering the Catholic Church. Their “House of Writers” at Farm Street in London became famous as a center of Catholic intellectual life. Father Caraman, as Mark Bosco, S.J., has noted, became Graham Greene’s confessor, while Martindale was a “constant correspondent” of Greene’s. (Among the archives at Farm Street is a letter from Martindale thanking Greene for sneaking in a bottle of whiskey for the two to enjoy.)

A car accident in Australia in 1928 left Martindale with chronic headaches for the rest of his life. Martindale was arrested in Denmark when the Germans invaded that country during the early days of World War II and was kept prisoner in Copenhagen until that city was liberated just days before the war in Europe ended. In the years following, he continued his busy schedule of teaching, preaching and writing. Martindale also wrote a number of articles in America (and the magazine reviewed almost every book he wrote) during this time, including essays on Sts. Stanislaus Kostka and Aloysius Gonzaga; a report from southern Africa (which hasn’t aged well) on celebrations of the Feast of Corpus Christi; essays critical of the Soviet Union; and a three-part series on Catholicism and paganism.

All this time, Martindale was also publishing almost a book a year. Their titles indicate his broad reach and multiple interests, including The Goddess of Ghosts, The Meaning of Fatima, In God’s Nursery, Old Testament Stories, Antichrist, Theosophy, Letters From Their Aunts (which—prove me wrong—sounds like the inspiration for Graham Greene’s later title, Travels With My Aunt?), The Creative Words of Christ and Can Christ Help Me?

Despite a background that might suggest a traditionalist bent to his theology, Martindale remained what we might call a theological progressive until his death in 1963 at the age of 83. He was particularly interested in a revival of the liturgy and wrote on the subject in Mind of the Missal. “At a time when resistance to any sort of liturgical change was deep rooted, and when, for that matter, most ‘liturgical’ propagandists were in effect antiquarians, he clearly saw the pastoral roots of a true liturgical advance,” Father Evans wrote, “the need to make a living participation in the Mass an essential foundation for a responsible Catholic spirituality.”

It was fitting, Father Evans wrote, that Martindale should die during the Second Vatican Council: “For no man could the mood of Pope John and his Council have been so complete a vindication of his work.”

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Apology for Belief,” by Alex Mouw. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Members of the Catholic Book Club: We are taking a hiatus this summer while we retool the Catholic Book Club and pick a new selection.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Father Hootie McCown: Flannery O’Connor’s Jesuit bestie and spiritual advisor

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane